Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

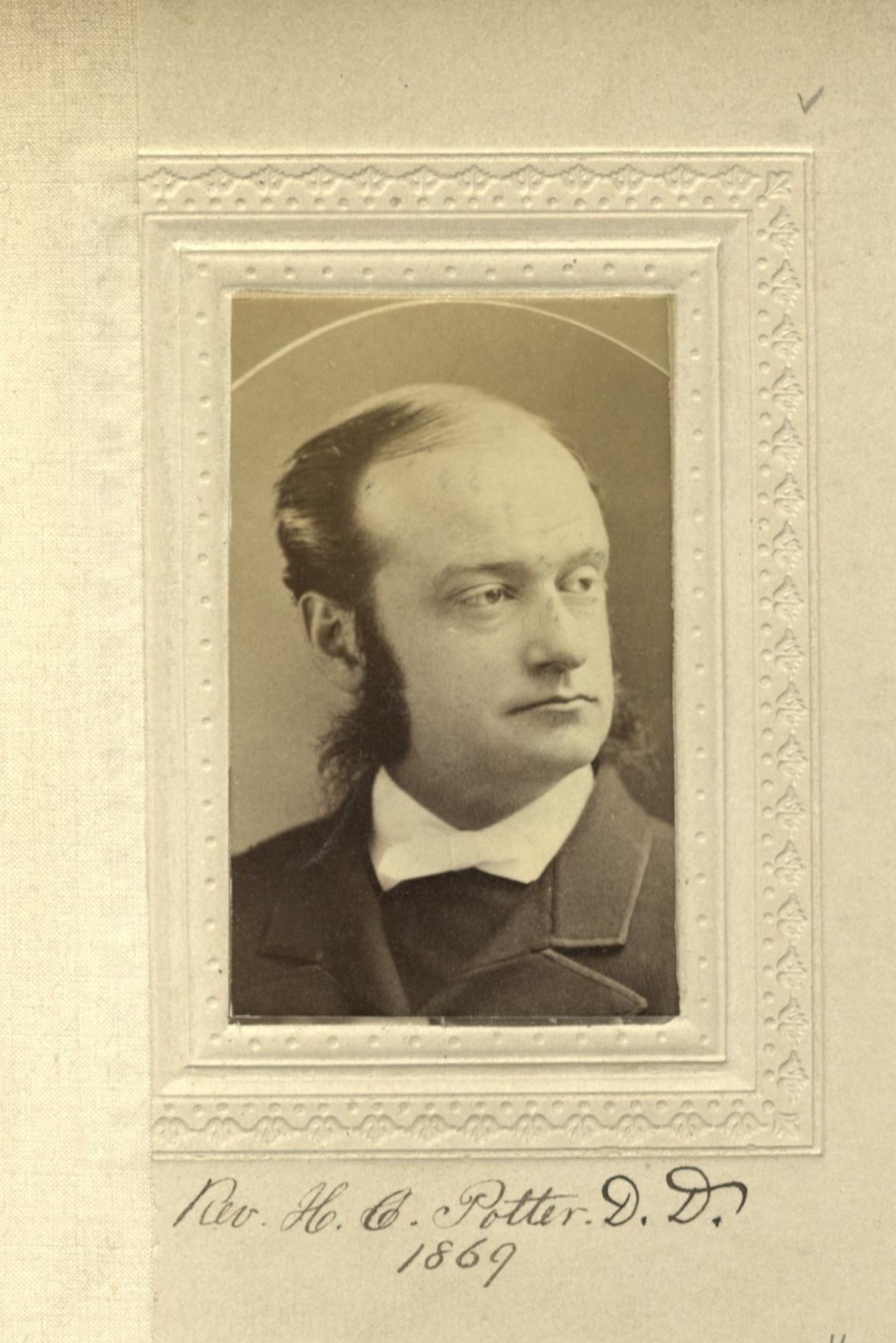

Henry Codman Potter

Clergyman/Bishop

Centurion, 1869–1908

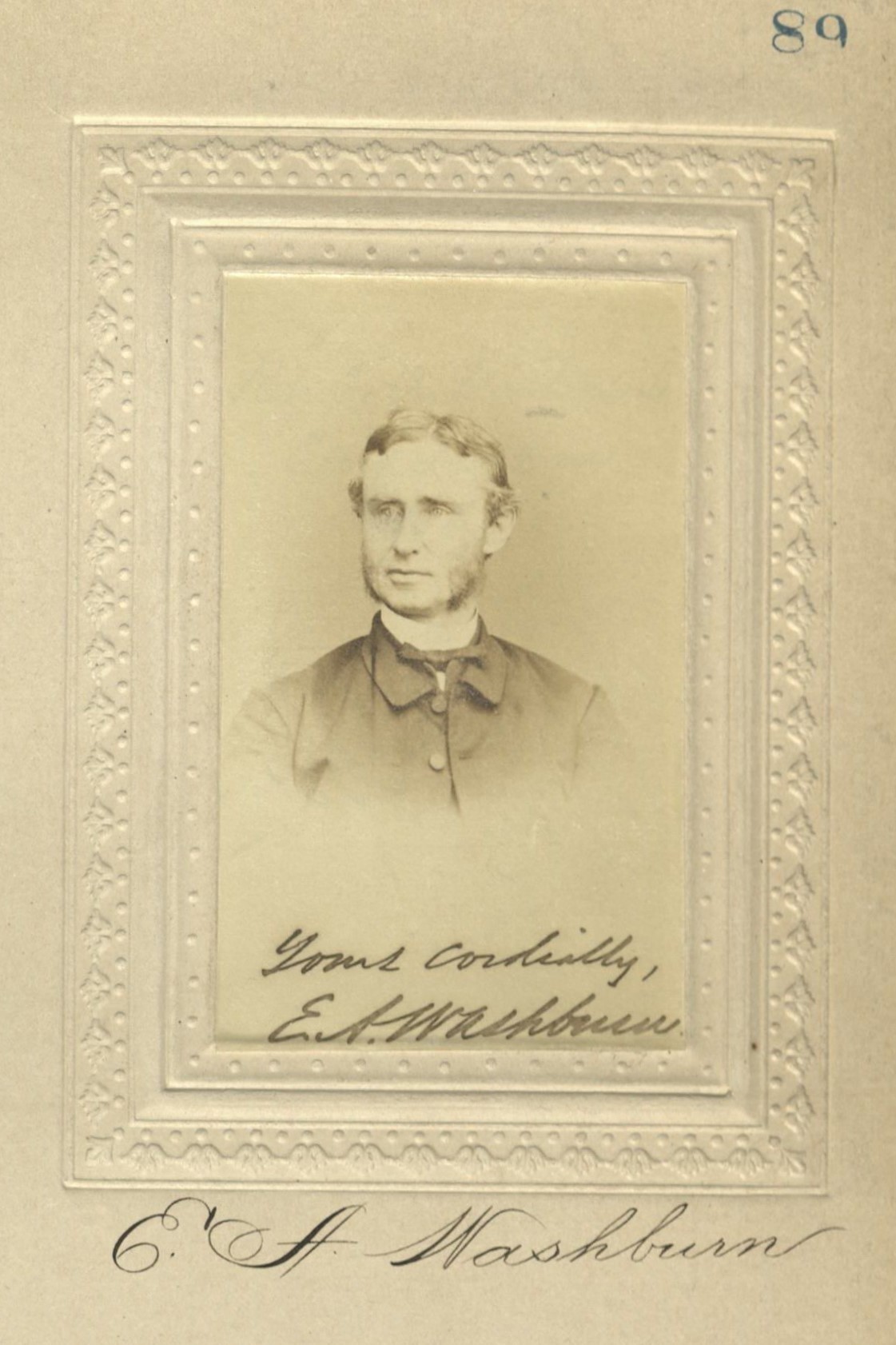

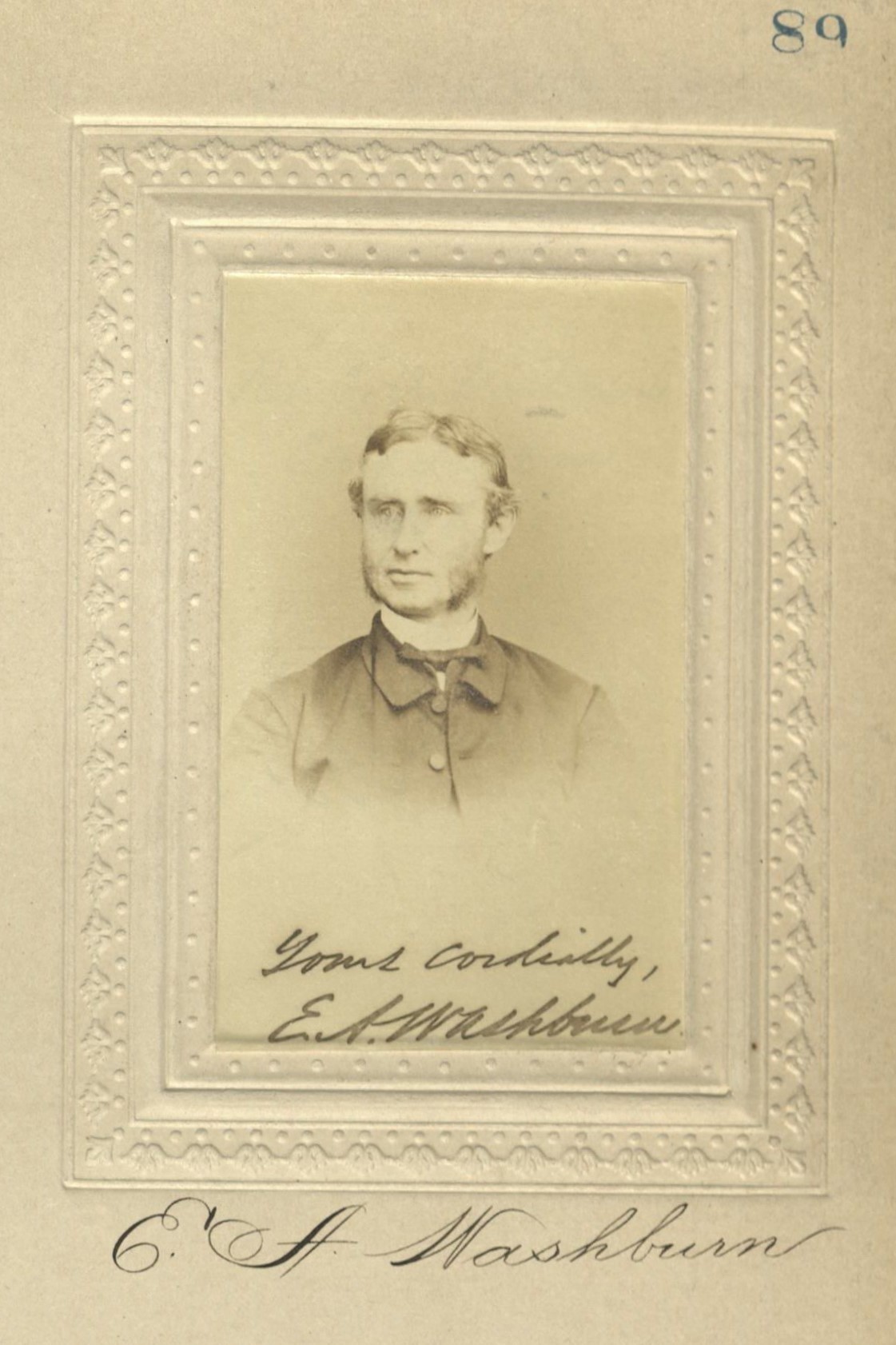

Edward A. Washburn and Benjamin H. Field

Schenectady, New York

Cooperstown, New York

Age thirty-four

Manhattan, New York

- Loring W. Batten

- William Edward Bond

- Charles Loring Brace

- John Wesley Brown

- William Adams Brown

- Arthur C. Coxe

- Thomas U. Dudley

- David H. Greer

- Charles Cuthbert Hall

- Richard H. Hunt

- Joseph Hutcheson

- Joseph Jefferson

- Edward Judson

- James B. Ludlow

- Lea Luquer

- Frank Marble

- William W. Moir

- George Francis Nelson

- William Wilberforce Nevin

- William Potter

- Richard S. Storrs

- Roderick Terry

- Alexander H. Vinton

Archivist’s Notes

President of the Century Association, 1895–1906; first vice president, 1889–1894; second vice president, 1883–1888; designated an honorary member in 1906. Brother of Clarkson N. Potter, Edward T. Potter, Howard Potter; half-brother of William A. Potter; brother-in-law of Launt Thompson; father-in-law of Charles Howland Russell and Edwin Tatham; grandfather of Henry C. Potter.

Available Digital Resources

Henry Codman Potter: Memorial Addresses at the Century Association, December 12, 1908

After his death, a series of memorial addresses delivered at the clubhouse by John Bigelow, Nicholas Murray Butler, Joseph H. Choate, Richard Watson Gilder, and Marvin R. Vincent was published as Henry Codman Potter: Memorial Addresses at the Century Association, December 12, 1908.

Century Memorial

Henry Codman Potter was for thirty-nine years a whole-souled Centurion steeped in the spirit of the Association, its Vice-President for twelve, its President for eleven years, an honorary member for two, and always a representative combatant for the high principles which are the chart of our membership: the loadstar [sic: lodestar] of our artists and writers, of our professional men in church, bar, medicine, and teaching, as well as of the merchant citizens who rally about them. In nature and training he was catholic-spirited and no one of us was strange to his personality. His stock was Quaker, his birth and education Episcopalian; his predilection was ecclesiastical, and his family were identified with Union College. But he never entered the portals of that or any other college; his discipline was mercantile, his career was in and of the world great and small; his education was in life both high and low. As a lover of his kind, the humblest and lowliest found him able to comprehend their point of view and sympathize with it practically, while his respect for the high office of the ministry and for himself enabled him to assert a peerage with the haughtiest. He was one of the few who perpetuated the fact and style of the parson, the personage to whom no phase of life is foreign, who was ready to advise, to aid, to warn, to punish—and to do them all efficiently. Fully aware of moral force as a compulsion, he could at times defy public sentiment in Church and State; and again he could arouse it for the success of his own plans as few who have lived in this city have ever done. With him Christianity was faith and dogma in part, with little regard for “doxies,” but especially it was life; life individual, life collective,—life here, life eternal. His parochial and episcopal duties were all performed with spirituality, but his clarion calls were for morals, private and public: for the cleansing of the slum, for the protection of chastity, for correction of abuse in what he believed the innocent pleasures of plain people, for pure civic administration, and for national righteousness.

The Bishop of New York is confessedly the foremost prelate of the Protestant Episcopal Church of America, and as such his services have been duly and officially set forth by the hierarchy to which he belonged. Furthermore, however, the holder of that high office is a social figure of great importance, whose demeanor and example, whose intimate talk and passing words, whose taste and personality must of necessity make a profound impression on the opulent and powerful of the metropolis. Among the men and women of that sort this Bishop was simply human, indifferent to his influence apparently and really, sharing the pleasures of their tables, discussing subtle questions of private living as a friend and an equal, ready with a clever quip and an apt illustration, prompt in repartee and frankly interested in the complex questions which make wealth a heavy burden. Of this activity little can be said, but much is known: the results are permanent and will long be remembered. And such is human nature that none is so interested in a great personage or so eager about him as those whose lives are humble and often sordid. With thousands of these he associated, not patronizingly with superior air, nor deprecatingly in the sackcloth and ashes of sentimentality, but, as before, in his proper person, standing for his own rights as for theirs, defending his viewpoint as he sought to understand theirs, openly critical but equally and helpfully sympathetic. His memory will long live for his defiance of what postured as constituted authority when it was prostituting the “red-light” district, a defiance which overturned a rotten city government.

A force of the greatest magnitude in church and society, Bishop Potter was likewise an important man in the world of education. To what may be called unmoral education he was quite as indifferent as he was bitterly hostile to immoral education. He fought for a training based on tried material; he demanded the truth through research, not merely the truth but the interpretation thereof by expert minds; Protestant to the core in regard to private judgment, he knew how largely that judgment is formed from authoritative presentation in all lines of thought and walks of activity. It was with zest that he lectured before universities and preached in their pulpits; it was with a conviction of responsibility that he so often made his own pulpit a professor’s desk; it was with a zeal almost sanctified that he gave his time and ripest opinion to the guidance of educational institutions. To teach the people how to ward off diseases, physical and spiritual, to instruct the masses how to inform their minds for the improvement of their condition, to guide American citizenship in acquiring clear views of public duty, to set forth the majesty of the moral law in private life as a foundation for all the rest—these were the lines of educational work in which his interest and action were untiring.

But while we commemorate the man in action, here and now we must joyfully recollect the man in repose. And in this very place on numberless occasions he could be seen and known as comrade and companion, a talker who could listen, a humorist without unfairness, a satirist without bitterness, a debater without rancor or self-consciousness,—in short, a man affectionate and yet powerful, determined yet chivalric and generous. Certain apparent inconsistencies of his public life could only be understood by familiarity with the workings of his mind when unbent. It was never too late for him to change it as he gained new light, nor did he know any keener enjoyment than debating opposite sides of a question until he saw it on every side. Consistency is, though a virtue, yet a minor virtue: it must yield in the highest type of mind to conviction of right. It was not mere fashionable tact that made this prelate a conciliator and kept a difficult diocese at rest for a quarter of a century, it was the insatiate curiosity to know the spirit, the temperament, the motive power in each and every man, and in his following: the consequent and categorical imperative was to give that man room for all that was best in him. Conspicuous station elicits high feeling alike of praise and of blame. Bishop Potter’s experience was not exceptional. But the end crowns the work and no spectator can ever forget the general appreciation of a good fight well fought expressed in the mien of a multitude who recently laid his mortal remains in the great cathedral for which he had labored, hoping that such a fane would express the majesty of the faith and yet afford a place of worship for the poor, the casual, the outcast; would be a refuge freely given, without charges and to all alike.

William Milligan Sloane

1909 Century Association Yearbook

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

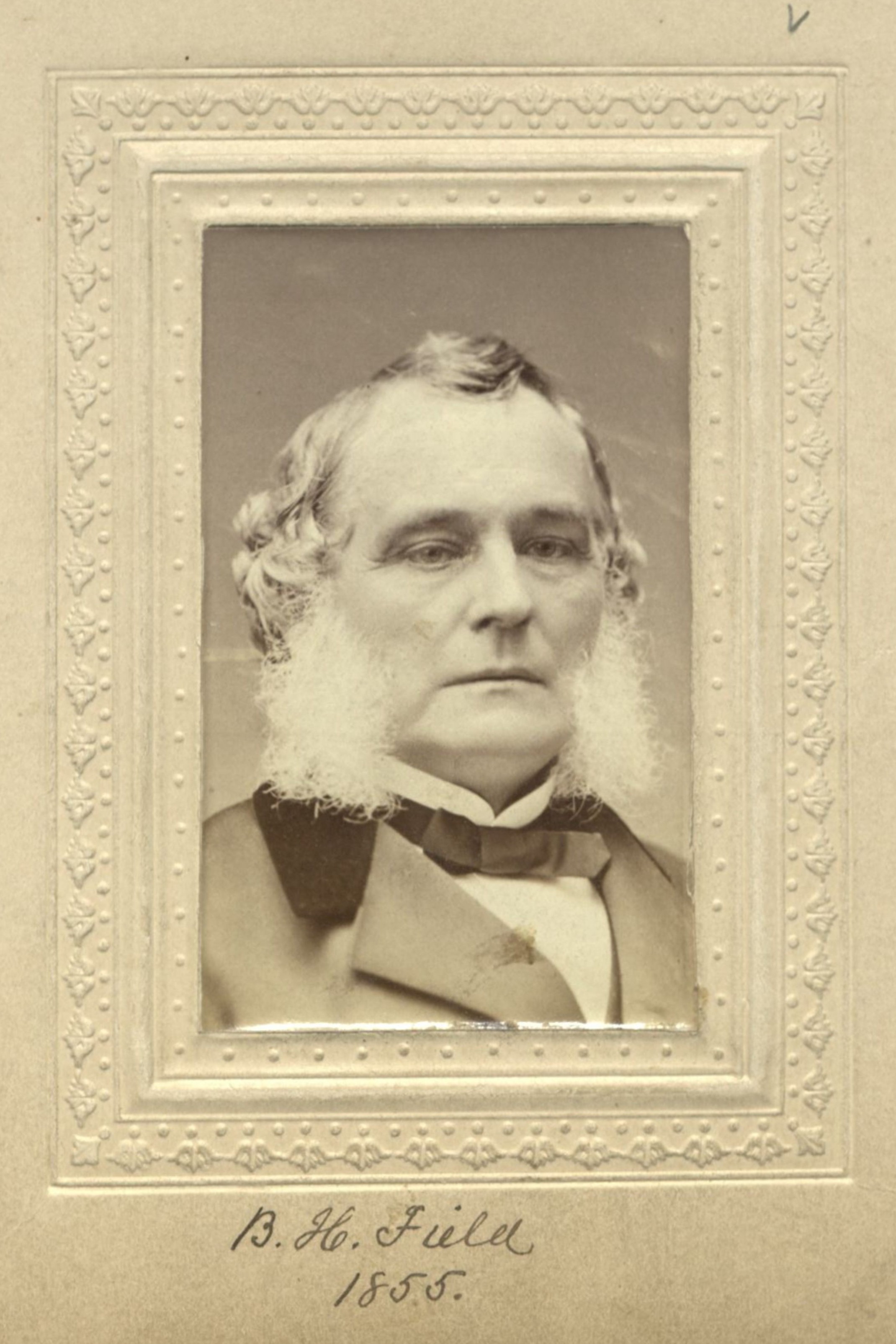

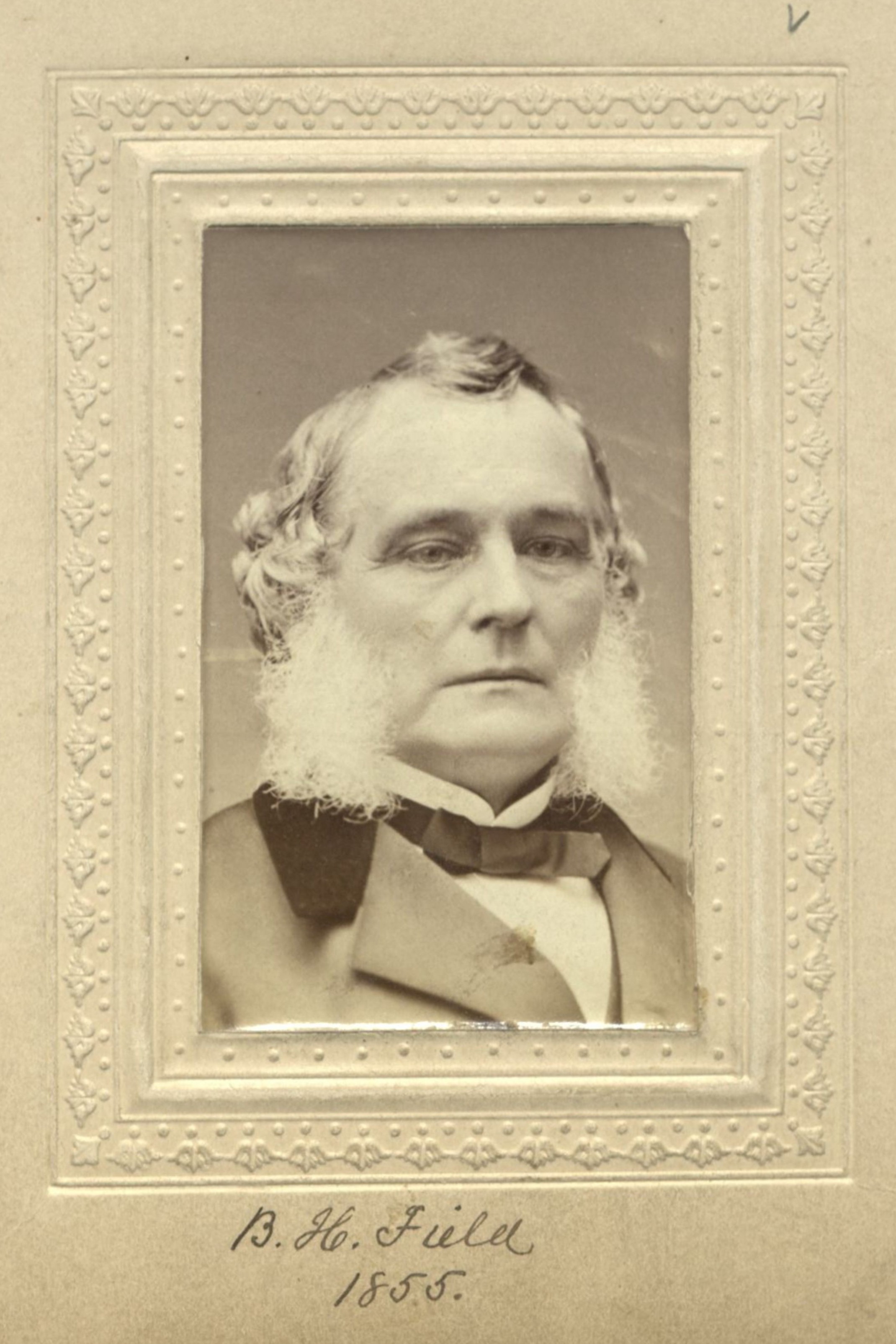

Benjamin H. FieldMerchant/PhilanthropistCenturion, 1855–1893

Benjamin H. FieldMerchant/PhilanthropistCenturion, 1855–1893 -

Newton M. ShafferOrthopedic SurgeonCenturion, 1889–1928

Newton M. ShafferOrthopedic SurgeonCenturion, 1889–1928 -

Walter ThompsonClergymanCenturion, 1894–1939

Walter ThompsonClergymanCenturion, 1894–1939 -

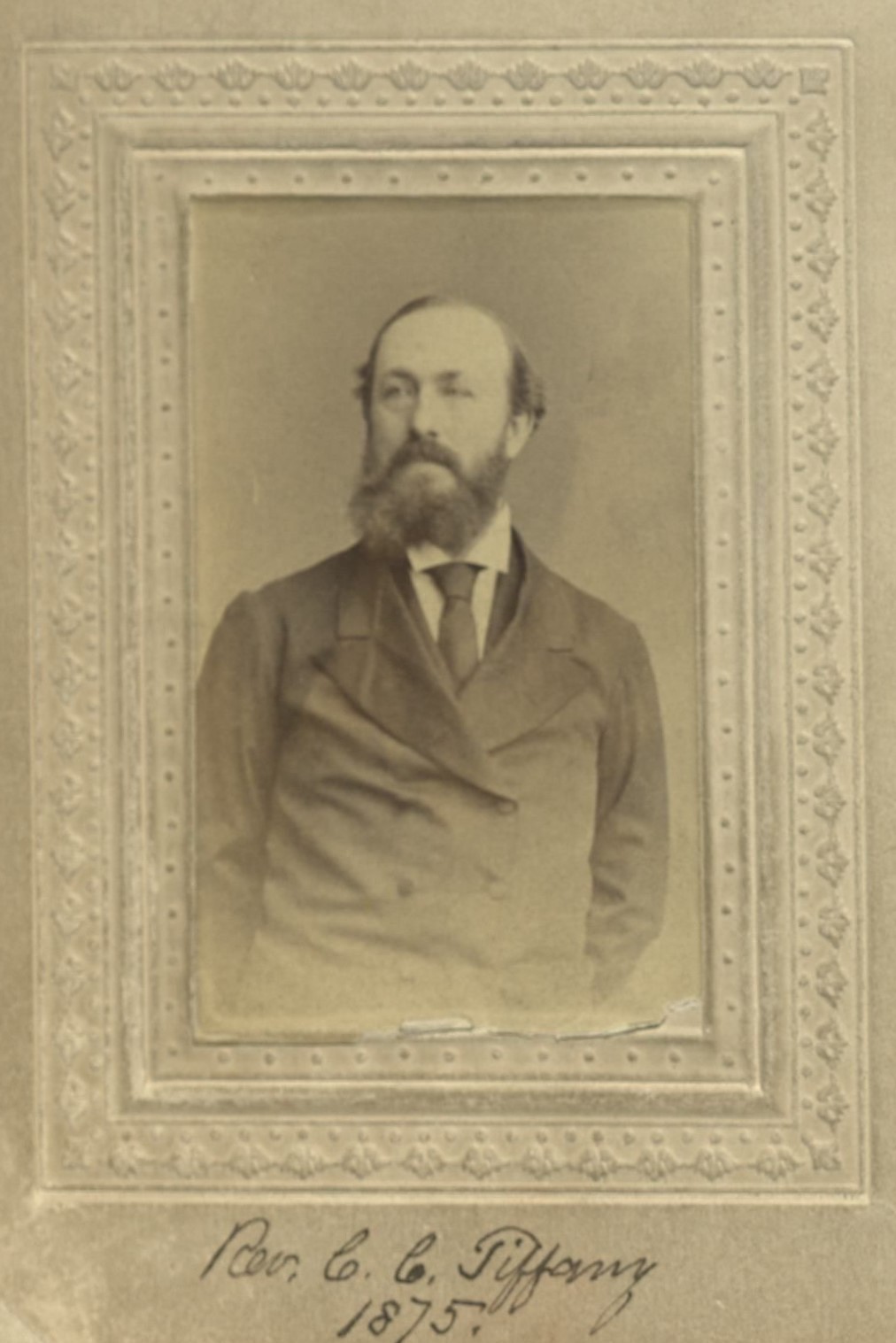

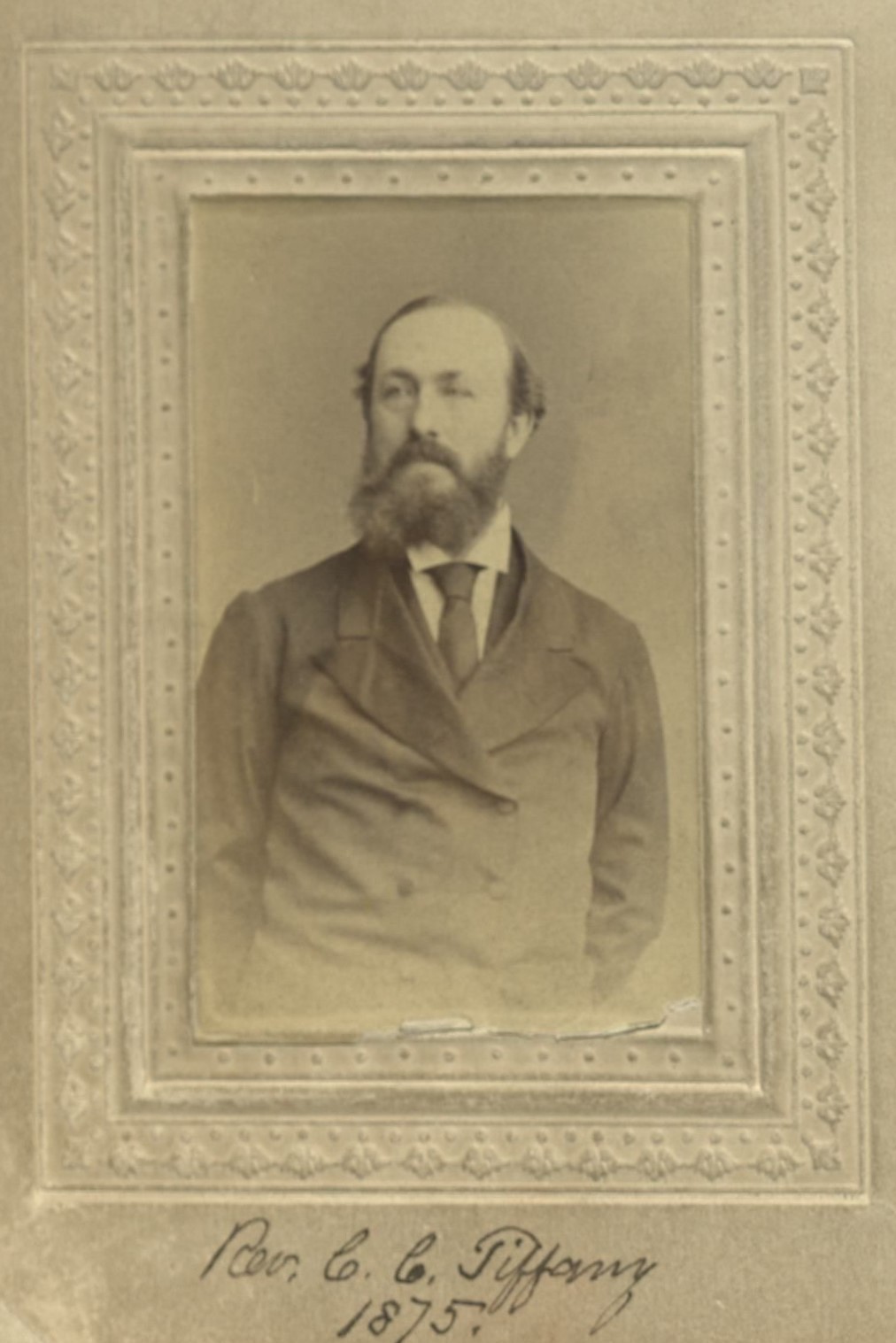

Charles Comfort TiffanyClergymanCenturion, 1875–1907

Charles Comfort TiffanyClergymanCenturion, 1875–1907 -

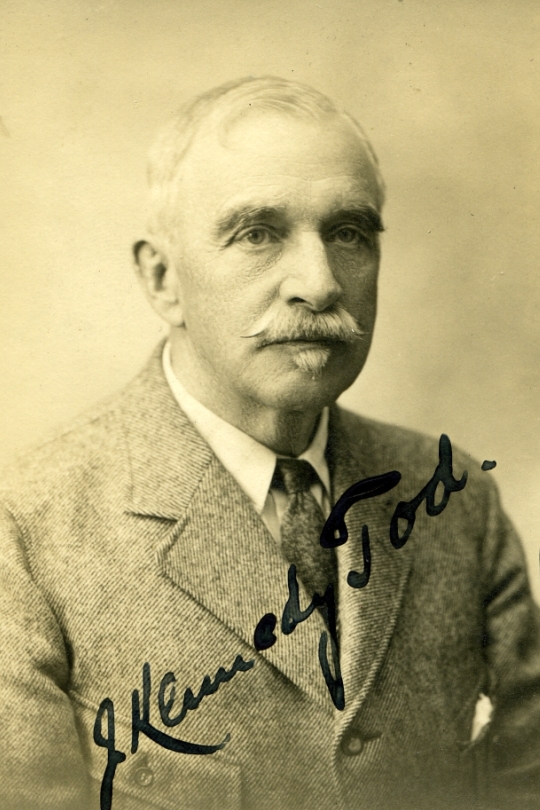

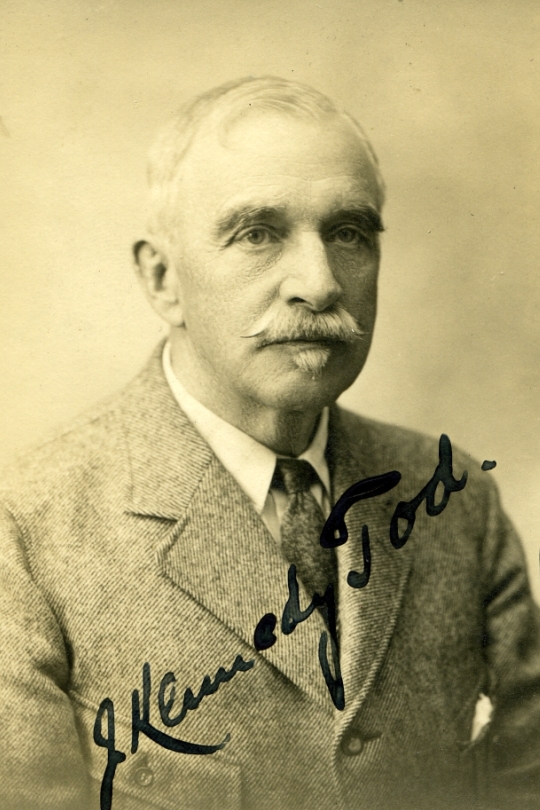

J. Kennedy TodBankerCenturion, 1886–1925

J. Kennedy TodBankerCenturion, 1886–1925 -

George W. VanderbiltGentleman/Art CollectorCenturion, 1889–1914

George W. VanderbiltGentleman/Art CollectorCenturion, 1889–1914 -

Edward A. WashburnClergymanCenturion, 1867–1881

Edward A. WashburnClergymanCenturion, 1867–1881 -

William F. WhitehouseLawyer/RailroadCenturion, 1887–1909

William F. WhitehouseLawyer/RailroadCenturion, 1887–1909