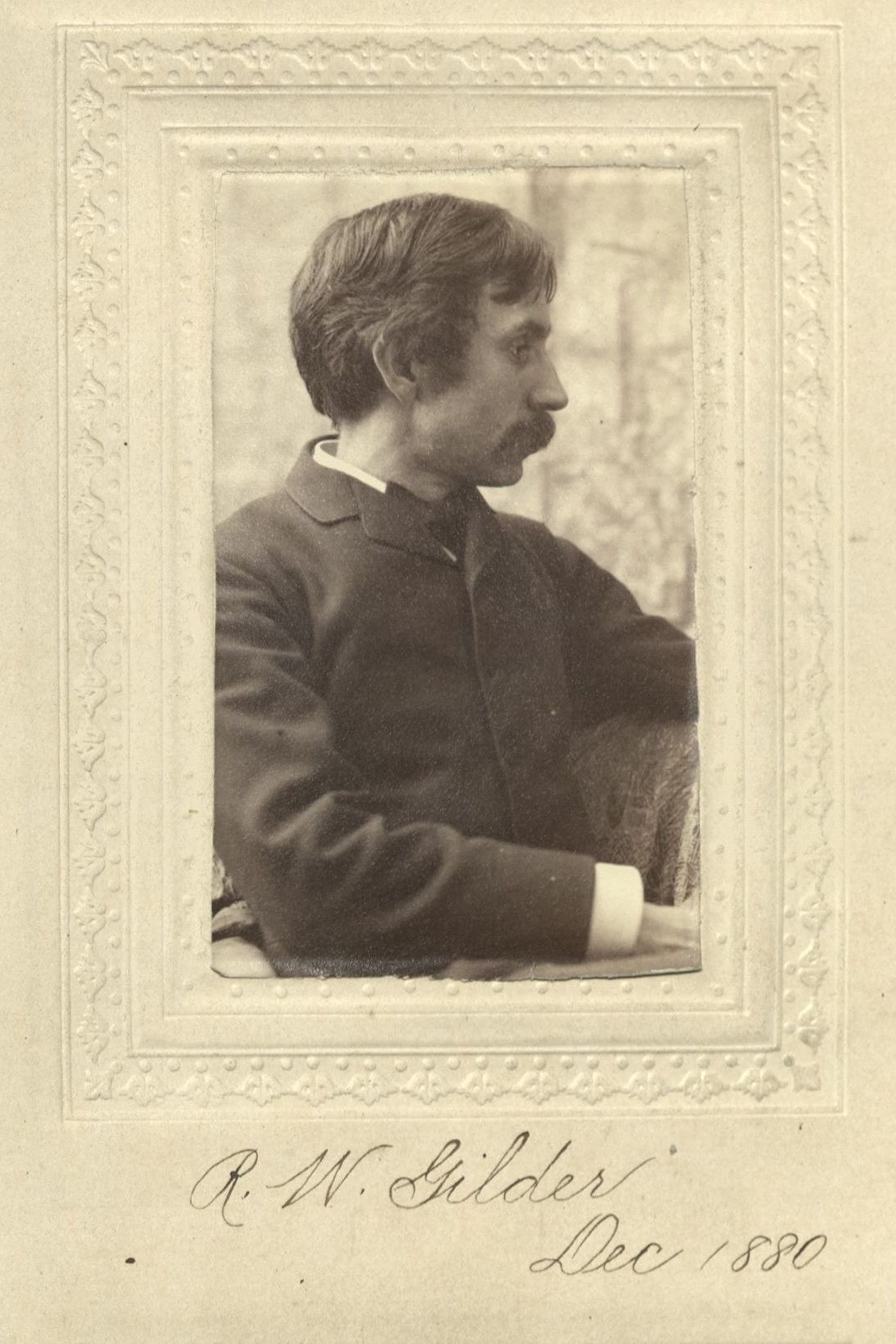

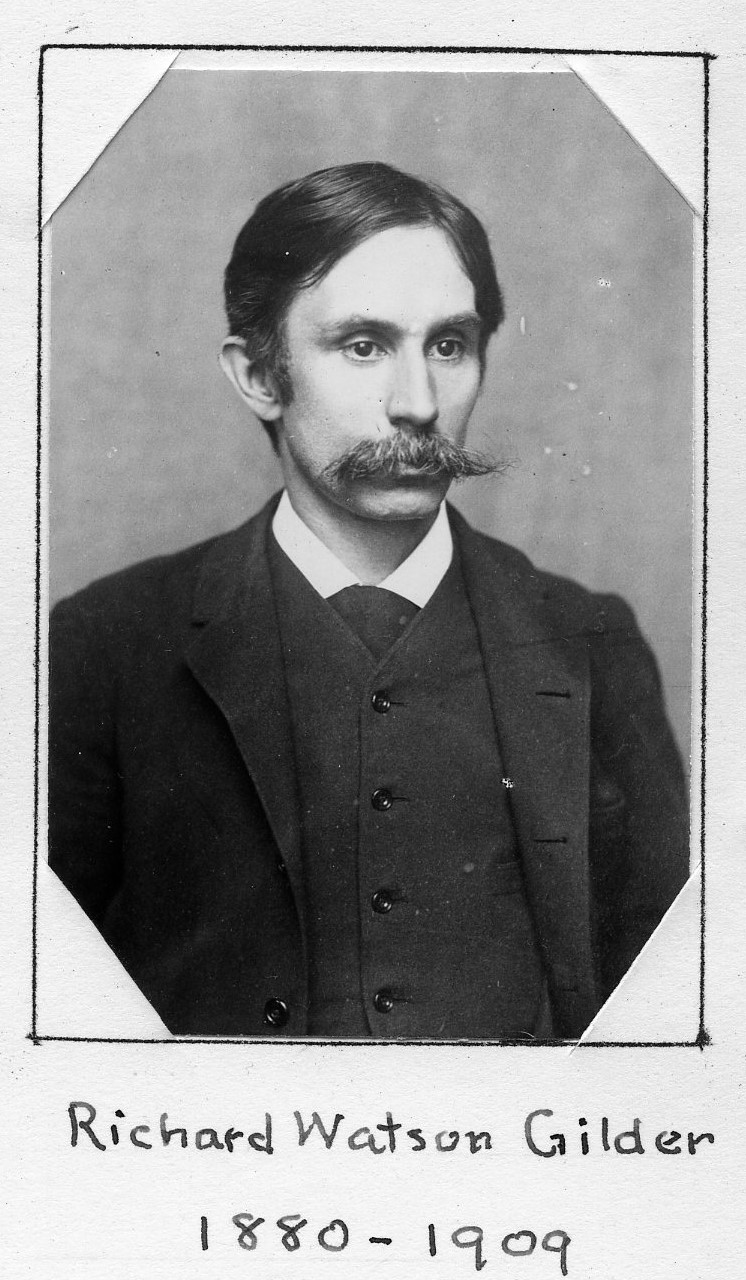

Editor/Poet

Centurion, 1880–1909

Born 8 February 1844 in Bordentown, New Jersey

Died 18 November 1909 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Bordentown Cemetery , Bordentown, New Jersey

, Bordentown, New Jersey

Proposed by Edmund C. Stedman and R. Swain Gifford

Elected 4 December 1880 at age thirty-six

Archivist’s Note: Brother-in-law of Charles de Kay; father of Rodman Gilder; grandfather of Richard Watson Gilder and Rodman Gilder Jr.

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

- William Sturgis Bigelow

- Clarence C. Buel

- Grover Cleveland

- Elgin R. L. Gould

- Ferris Greenslet

- John Fletcher Hurst

- Rudyard Kipling

- Henry Cabot Lodge

- Brander Matthews

- Charles E. Merrill

- Frederick Middlebrook

- John W. T. Nichols

- Franklin H. Sargent

- Benjamin E. Smith

Supporter of:

Century Memorial

Richard Watson Gilder had been a Centurion of the grand manner for nearly thirty years when he laid down his life at sixty-five; a full, strong life which he had offered on the altar of humanity. Men give in different ways; he gave in effort, in sympathy and in song, gave a fortune, a wealth, a personality of qualities partly inherited but largely acquired by the diligence which makes those faithful in few things the rulers over many things. Frail in body and sometimes in health, he feared no struggle, he shrank from no duty, the force was created in the using, and gentleness begat tenderness, which led to conviction and success.

He was proud of his ancestry, the pretensions of simple lives nobly lived where he was born, on the banks of the Delaware in New Jersey. His sire was a preacher, a teacher and a writer. The son learned type-setting from the local printer almost in infancy, and, soon after, the boy was setting the type of his own compositions in the school paper of his father’s new school in Long Island; with comrades he wrote and manufactured a campaign newspaper in the interests of Bell and Everett. The Civil War beckoned to both father and son, but higher duty in one case and poor health in the other checked both for a time. But, in the crisis of sixty-three, Richard volunteered and was a soldier so far and so long as to have been under fire. The father enlisted as chaplain and died in a small-pox hospital for soldiers. When mustered out Gilder was attracted toward both law and business, but narrow means turned the choice; he was for a time an employee of the railway, then a reporter and a newspaper editor and at last found rest for the sole of his foot in the office of “Hours at Home,” whence he almost immediately graduated into the managing editorship of that magazine which later became The Century, of which for nearly a generation he was editor-in-chief.

Gilder was above all a poet, his nature was melodious, and he marched through life to the rhythm of his own verse. He collected his pieces first in 1875, and what he cared to preserve is in the volume published something more than a year ago. Posterity alone renders the final verdict, but we who knew him find inspiration in his lines. There is the love of man, reverence and trust in the Most High, the beauty of nature, human and material, the charm of relation between the inner and outer worlds, joyously expressed. The special mark of it all is aspiration; while force and wealth could not exalt the state, as he wrote in lines to Lowell: “One great name can make a country great.”

Editor and poet, he was also a fearless reformer. The poor of New York may rise to call him blessed, for, thanks to his efforts, their homes can never again be the stews they were before he marshalled the hosts of reform. To his commission our crowded quarters owe their parks, and by it careless landlords were forced to supply the water in tenement halls, which is an aid to cleaner living. Any menace to the city’s beauty aroused a scorn which dipped his pen in vitriol; any possibility of adding to its charm found in him an unwearied supporter. The mental and moral safety of little children, the civil service reform, the safeguarding of literary property: there was not a struggle for righteousness in which he did not deliver strokes of his battle axe. But his crowning glory is the insight with which he discovered ability and encouraged the rising craftsman of the author’s guild. Those who are wielding the pen in a coming generation will rise to call him blessed.

We miss him here; other like bodies enjoyed his presence, but here he gave his whole self. Others wondered sometimes, we understood always. To the gatherings here he turned, when weary, for refreshment; when wavering, for advice, and, when discouraged, for the sympathy which gave him new vigor. If anywhere his example and memory can serve as inspiration, it is to those who survive him here.

William Milligan Sloane

1910 Century Association Yearbook