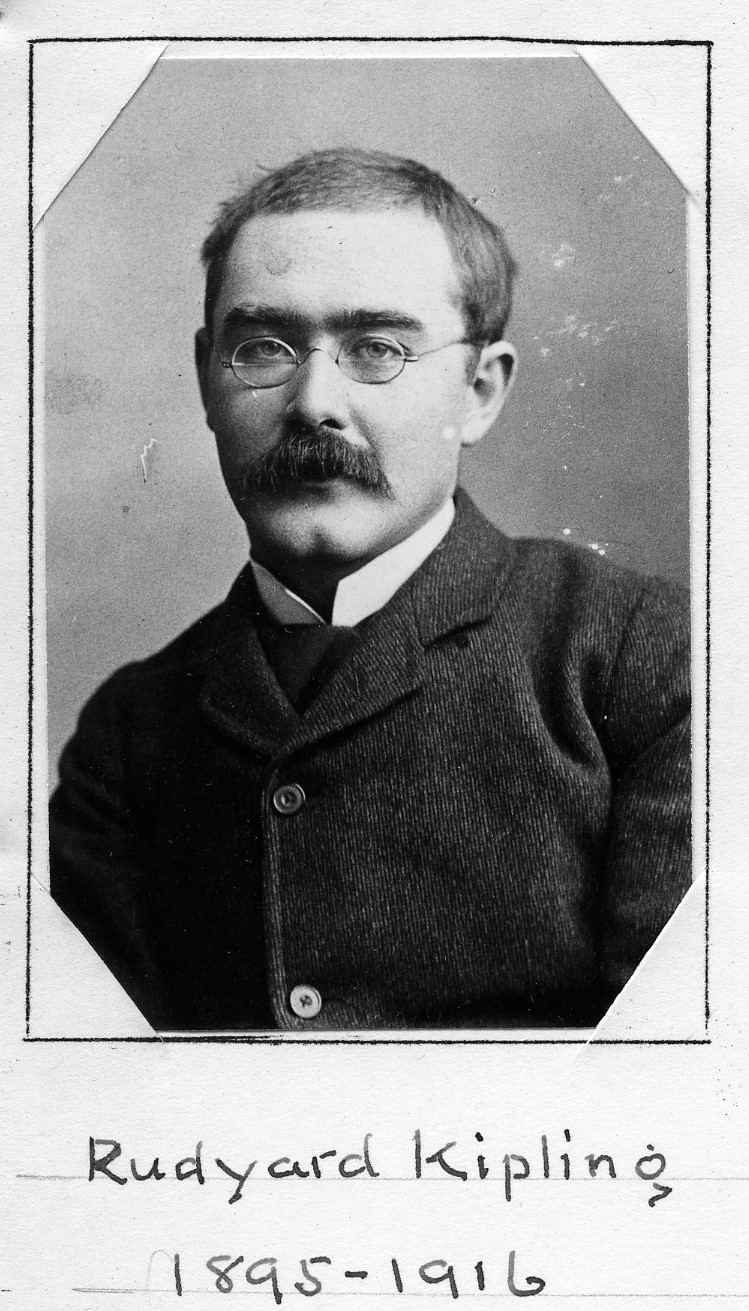

Author/Poet

Centurion, 1895–1936

Born 30 December 1865 in Mumbai, India

Died 18 January 1936 in London, England

Buried Westminster Abbey , Westminster, Greater London, England

, Westminster, Greater London, England

Proposed by Lockwood de Forest and Richard Watson Gilder

Elected 2 November 1895 at age twenty-nine

Archivist’s Note: Grandson-in-law of Joseph N. Balestier

Century Memorials

It would not occur to many present-day Centurions to associate Rudyard Kipling with the Century. Even to older club-men, his place in recollection is that of an East Indian who, in the later Eighties, suddenly burst into ballad and folk-lore. To the younger generation, he is an all but forgotten British writer, whose poems and stories mostly repose in dust-covered volumes on the upper shelf. Yet Kipling had his turn at America and the Century. He had been a fellow-member of ours during forty-one years; only a dozen of our living non-residents joined the club before him. The interesting record stands upon the Century’s older-time books that Rudyard Kipling was proposed by Lockwood de Forest, seconded by Richard Watson Gilder, endorsed by John Hay, Edmund Clarence Stedman, Frank Dempster Sherman, John Kendrick Bangs, Henry Rutgers Marshall and Augustus Saint Gaudens; that he was elected to membership in November, 1895.

All of those sponsors for Kipling’s membership have long since passed to the permanent Absent List; their own names read like recital of the Club’s older traditions. Yet there was a time, not long before the dawn of the Twentieth Century, when Kipling used to sit regularly with a few chosen spirits at the corner table in the dining-room. He lived in this country long enough to have qualified as American citizen, but that was certainly not his wish. His poems, written during thirty-three years, were so many that the inclusive published collection of them required a book of 773 pages. But among them perhaps only one strikes off his impression of America, and that was not accepted by our people as a compliment. There was some truth in its lines regarding the American of 1894, a quarter of a century before the Prohibition Amendment, describing

“The cynic devil in his blood

That bids him mock his hurrying soul;

That bids him flout the Law he makes,

That bids him make the Law he flouts.”

But Kipling was no more merciful to his own people’s foibles than to ours. England also, notwithstanding Kipling’s patriotic outbursts of 1899 and 1914, could not miss the sting of the lines which concluded his famous “Recessional,” published at the Victorian Jubilee:

“For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy people, Lord.”

But Kipling was not England-born any more than America-born; his was always the colonial viewpoint, which lacked the conventional.

By rather common judgment, he should have been Poet Laureate of England during many years. Possibly Kipling’s own idea of that office, as Tennyson was said to have described it, was as a post which ought to have been abolished along with that of Court Jester. His own expressed opinion was that he had been disqualified by his lines on a long-past unnamed English king, to the effect that

“He ruled the land with an iron hand,

But his mind was weak and low.”

The British public, however, regretfully though quite unanimously, ascribed rejection of his name to his ballad of the Nineties, in which the cockney soldier advises people to

“Walk wide of the Widow at Windsor,

For ’alf of Creation she owns,

We ’ave bought her the same with the sword

an’ the flame

An’ we’ve salted it down with our bones.”

This was not Victorian age propriety.

But Kipling will retain his place in English literature—perhaps more surely as time goes on. Nobody else has voiced as clearly and spontaneously as he the spirit of the England in the later Victorian Era. No poet of our times has given to the English-speaking public, even those who have forgotten the origin of the lines, such phrases as “The white man’s burden,” “There’s no discharge in the war,” “I’ve taken my fun where I found it,” “The tumult and the shouting die,” “Lest we forget,” “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Exactly what would have been Kipling’s tribute of verse to the recent extraordinary episode of the middle-aged king who resigned his throne because he was entangled in a matrimonial compact with an American divorcee, one can only guess.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1937 Century Association Yearbook

Kipling was born in Bombay, British India, and when he was six, he and his younger sister were sent from his beloved Bombay to Southsea (Portsmouth), to be cared for by a couple that took in children of British nationals living in India. He stayed there six years, recalling it decades later with horror. After attending school in Devon, Kipling obtained a newspaper job in Lahore (now in Pakistan). Writing at a furious pace, Kipling published seven collections of short stories before leaving India in early 1889, eventually settling in England.

In London, Kipling met a young American writer and publishing agent, Wolcott Balestier, who subsequently died of typhoid fever in 1891 just after he and Kipling completed the novel Naulahka. The New York Times obituary noted that he was the grandson of Joseph N. Balestier, “one of the founders of the Century Club” [sic: Balestier did not join the club until 1856, nine years after its founding]. In January 1892, Kipling married Wolcott’s sister Carrie Balestier, whom he had met a year earlier. Henry James gave the bride away.

The couple settled on a farm near Brattleboro, Vermont, not far from the Balestier family estate. With the birth of their first child, the family relocated to a cottage nearer to Carrie’s brother, Beatty, and Kipling named the house Naulakha (correctly spelled) in honor of Wolcott. Naulakha was built by Henry Rutgers Marshall. Within four years, he produced the Jungle Books, a novel (Captains Courageous), and a profusion of short stories and poetry. In 1896 the Kiplings moved to Devon, England, and in the first decade of the 20th century he was at the height of his popularity. In 1907 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, the youngest writer ever to receive the award. Kipling kept writing until the early 1930s and died in January 1936. He joined the Century in 1895 and remained a member for 41 years.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)