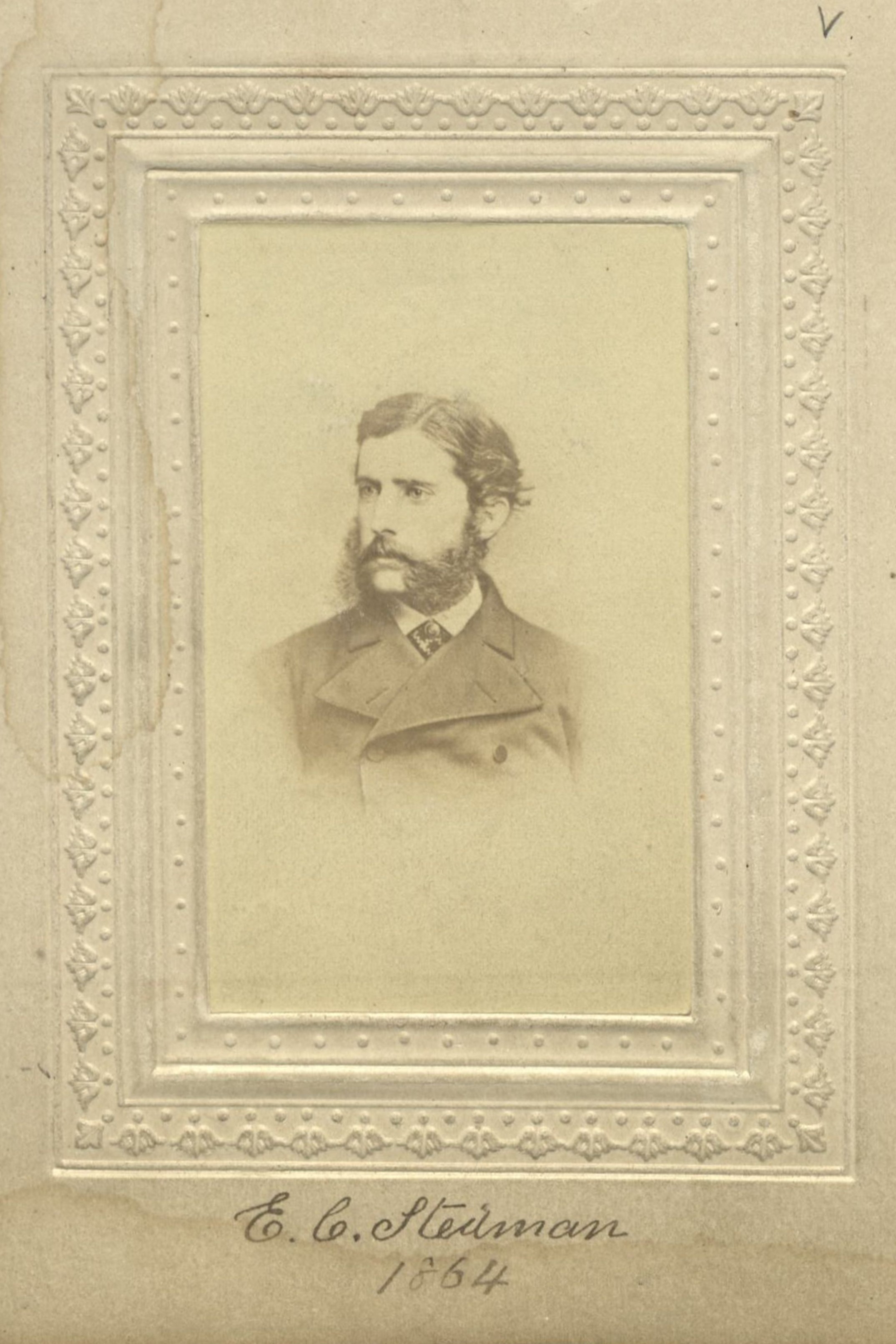

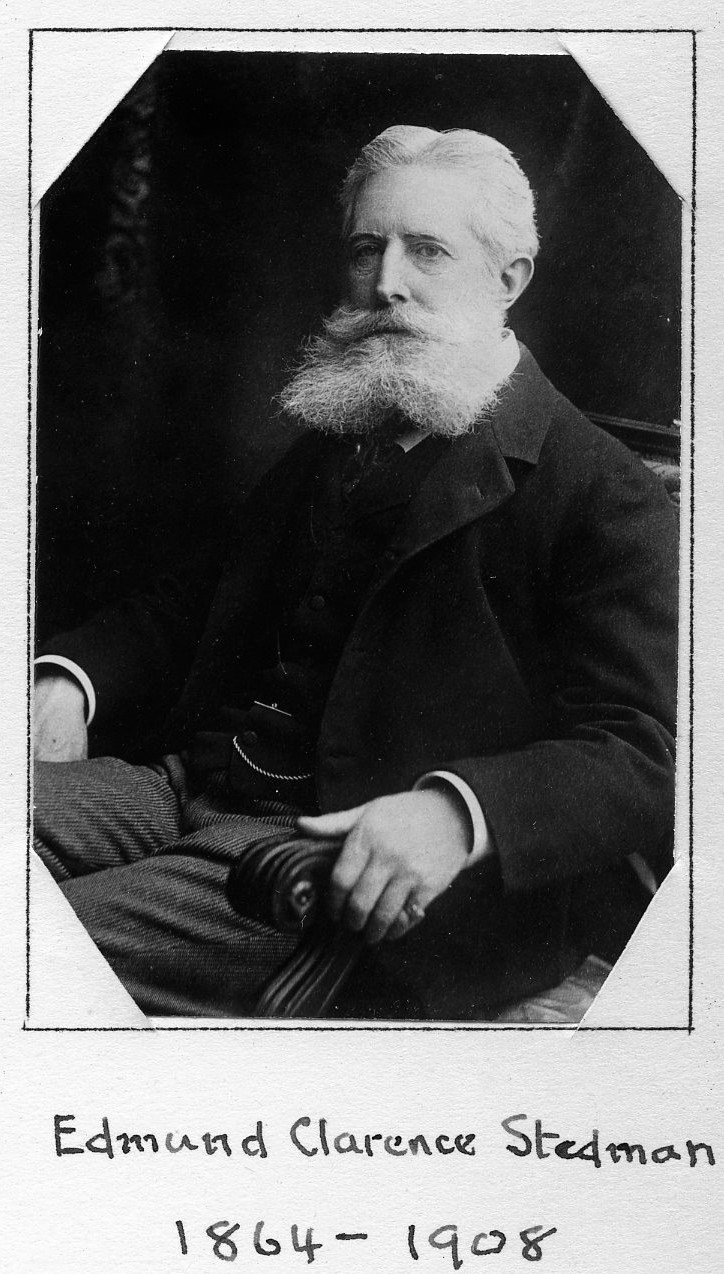

Poet

Centurion, 1864–1908

Born 8 October 1833 in Hartford, Connecticut

Died 18 January 1908 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Woodlawn Cemetery , Bronx, New York

, Bronx, New York

Proposed by James L. Graham Jr., Bayard Taylor, and Eastman Johnson

Elected 3 December 1864 at age thirty-one

Archivist’s Note: Second vice president of the Century Association, 1906–1908. Father of Arthur Stedman.

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

- Wilson Barstow

- Frank S. Bond

- Walter B. Chambers

- Moncure D. Conway

- Edward W. Dodd

- George Walton Green

- Levi Holbrook

- William Dean Howells

- Laurence Hutton

- Thomas A. Janvier

- Robert Underwood Johnson

- Hamilton W. Mabie

- Thomas Moran

- Thomas Nelson Page

- Anson D. F. Randolph

- Clinton Scollard

- J. Blair Scribner

Supporter of:

Century Memorial

Edmund Clarence Stedman was for forty-four years a loved Centurion. For us he was the one of his name and fondly we called him “Stedman,” dropping all the rest, as did those in other circles where he was pre-eminent; indeed the country and the world were indifferent to his given names and to the many suffixes and titles with which his full name had been adorned, for above all the honors which he wore so gracefully was the crowning honor of his life, his work, and his personality. He came of old New England ancestry, of a stock that battled for fatherland, that cultivated learning and poetry, that sent him to Yale as a matter of course, and which, at the crisis, comprehended perfectly the impetuous onset of a nature which made impossible the completed routine of academic life, or later the restraints of a local career. Like millions who live and die without a chance to quaff the full cup of leisure, in draughts that commingle the bitter and the sweet, he belonged to the ranks of labor: but unlike most of these he was one of the elect few who sweat and toil but who likewise breathe the sweet airs of Arcady. His record as journalist and war-correspondent, as financier and banker, as family guardian and bread-winner, was marked by trials and sorrows beyond what most are called to endure. Yet he rose in victory above them all and on the highway of literature, as poet, critic, companion, and guide, his talent marched cheerfully, unweariedly, successfully. He long outlived the conditions and the age which stimulated his early efforts; he survived his companions and friends: Curtis, [George] Ripley, Taylor, Stoddard, [Thomas Bailey] Aldrich and the others; he might have been a mourning, solitary man in the last period of his life. But no, there was honor to be won in the struggle for copyright, there was the throng of coming writers to be encouraged, there was the new age of aerial navigation to be imagined and brought under law, and above all there were the dear friends who thronged The Century and found the renewal of their powers in his talk, as he did in theirs. If present cheerfulness and the forward look be marks of youth, the latest epoch of his life was the youngest.

His place in literature was felt, I think, by himself, and those in his confidence, to have been virtually fixed in the age to which his life belonged and in which he was a type. Poetry was his vocation, criticism his avocation, and all the rest—the banking, merchandising, agitating for reform—was the struggle on which he spent the surplus energy which he seemed to gather from exertion and experience. Imperious ideals drew him on, but time and space and stern necessity both impelled the intellectual powers he used and set limits to the soaring of his fancy. He was strong and fearless in his thought, but he was cautious and conservative in its expression. His selection and criticism of contemporary verse in both English-speaking lands were so tactfully done that in his honest, unsparing judgments there was no sting. He was too frank to be biting or petulant. His quips, jests, and bon-mots were trenchant and accurately aimed, yet no one took them otherwise than in good part. In conversation, as in his studied verse, the transitions from grave to gay, from fancy to reality, were constant, and revealed the inner light that showed the way in his conduct of life.

Philosophies and dogmas were detestable to him; the personality of what he saw as a natural spirit, the links of passing times and phases with each other, and with the present, interested him chiefly. He liked to rehearse his own ancestry as well as any other New Englander, but he could not rest in the laurels of those who were gone; their example spurred him to ever greater exertion. So with the phases of his life: he had no time for vain regrets; his was the pensive melancholy which is creative and rebuilds before the earthquake shock has ceased. While therefore he was in a way cosmopolitan, he was far more metropolitan. The larger the town, the more parochial its divisions and the greater its self-assurance. There is an urban naïveté comparable to rustic credulity. This narrow complacency Stedman abhorred, yet he realized that New York was an epic of America, if not indeed the epic. Its heterogeneous multitudes, its gigantic passions, its concentration of power, its radiation of influence outward into all the earth—behind these all there must be a creative organism, elusive but real. This he sought diligently to find, and if it never revealed itself fully, it did at least partially as one manifestation of the world spirit, as both a descendant and a progenitor. Many of its avatars he sought to express.

But we celebrate him chiefly as the ideal Centurion. Admitted at thirty-one to the select company of older men who formed this association, his youthful vigor energized and realized the aspirations of his seniors. He was largely responsible, if not entirely, for the founding of this library and the establishment of the Committee on Literature. There was no honor he so highly esteemed as the opportunity to render service here, and he lamented the subtle changes which seemed to exclude from our membership the younger members of the literary guild, who maintained, as he felt, the sound tradition of the older American literature. But, impatient as he sometimes was, his devotion was strengthened with every year. He wrote our anniversary ode with tender insight; he was faithful in the performance of the special duties we imposed upon him; his dearest friends were the companions he found here, and his stately obsequies were conducted, as was fitting, by Centurions, with the delicate sensibility associated with family ceremonial.

William Milligan Sloane

1909 Century Association Yearbook