Author

Centurion, 1886–1929

Born 21 February 1852 in New Orleans, Louisiana

Died 31 March 1929 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Edward Eggleston, Richard Watson Gilder, and Edmund C. Stedman

Elected 2 October 1886 at age thirty-four

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

The occasional lament, that club life in the Century nowadays is not what it used to be, is based ordinarily on absence of the dozen sociable groups which, in older pre-war days, invariably crowded of a Saturday night around the little second-floor tables; tossing back and forth the ball of conversation, humorous or serious, on literature, art, politics, science, and matters of general human interest. The Saturday night commemorated in Turner’s drawing that hangs on the Club-house walls, and strikingly recalled by the Club’s first moving picture—the assemblage in which some notable conversationalist was sure to be the centre of one group, some well-known painter or writer or scientist the centre of another, with the happy privilege for the undistinguished Centurion of moving from group to group and receiving in each a cordial greeting—this is now largely tradition and reminiscence. Prohibition may have had something to do with disappearance of the old-time Saturday night; increasingly general observance of the out-of-town week-end has had more. Yet a chance assemblage of good talkers in the after-luncheon or after-dinner group of the Graham Library, the Club’s enthusiastic response to the “special dinners” on monthly-meeting nights, the jovial troop of New Year’s Eve, bear witness that at least the old Century spirit of convivial intercourse survives.

In those old-time gatherings, as in the exchange of conversation around the dining-table, Brander Matthews was an outstanding figure. Always in his own characteristic vein, Matthews was the embodiment of entertaining talk and reminiscence. He would have found a ready place in the famous social clubs of other times. Dr. Johnson’s club might have irked him; for Matthews disliked monopoly of talk or arrogance of judgment, and himself never indulged in either. But he could certainly have capped epigrams with Shakespeare and Ben Jonson at the Mermaid; indeed, the drift of Matthews’ favorite ideas would have fitted him instantly into that celebrated circle. Like the Elizabethans, Matthews had little interest in political affairs, not much in problems of society, none at all in economics. But on his own peculiar subjects, notably the drama and the English language, his background was extraordinary. He knew the Elizabethan stage as if he had lived in the reign of the great queen, and his knowledge was not the critic’s judgment of varying versions or disputed texts, but intimate acquaintance with scenery, stage expedients, and program personnel. Sometimes this intimate knowledge disconcerted his interlocutors. A fellow-Centurion, having watched with delight Jimmy Powers’ highly amusing portrayal of the tapster in The Players’ presentation of “Henry IV.,” remarked to Matthews on its illumination of a scene which, read in the text, seems pointless and superfluous; adding, with some little triumph of discovery, that Shakespeare surely must have had a Jimmy Powers in his company at the Globe and must have written the scene for him. “Yes,” Matthews responded, reflectively; “that was Kemp.”

This fund of knowledge regarding stagecraft in the larger sense, historic and contemporary, Matthews was able so to impart to his classes at Columbia in dramatic art that he sent out from his courses some of our most ingenious and imaginative playwrights. Yet, curiously enough, Matthews himself achieved little, and made little effort to achieve it, as dramatic critic. Some of his own impressions of dramatic performances were a bit surprising. In his published reminiscences, he avowed his most vivid recollection of great moments on the stage to be identified with Booth as Richelieu, not Hamlet; Ellen Terry as Beatrice, not Portia; Irving as Mephistopheles, not Mathias in The Bells. His own strongest literary ambition, Matthews confessed, was “to write plays and have the perilous pleasure of seeing them performed.” He had that perilous pleasure, but the half-dozen plays from his pen which reached the foot-lights won only conventional reception. As with his similar efforts in the field of short-story writing, plan and mechanism were always admirable, but vivid human interest, conception of human mentality in a dramatic situation, insight into the depths and heights of human character, seemed to have been denied him. Perhaps the reason was his own greater interest in the externals, rather than the imagination and philosophy, both of the stage and of everyday life.

Disappointment of his highest professional ambition never embittered Matthews; rather it stirred his abundant and effervescent sense of humor, even at his own expense. He himself told appreciatively of the manager who returned one of his manuscript plays, with the remark that “I like the people in your piece and the talk is excellent, but I don’t care much for the plot; can’t you use those characters and that dialogue for another story?” He narrated with particular relish the imaginary incident in which the chance acquaintance of an aspiring playwright had accepted a pass for the first-night presentation. At the end of the first act, as Matthews used to tell it, the holder of the dead-head ticket applauded loyally though the rest of the audience was silent. At the end of the second act the friend applauded and the others hissed. At the end of the third, the friend went out to the box office and bought a ticket; then, returning, hissed on his own account for the rest of the performance.

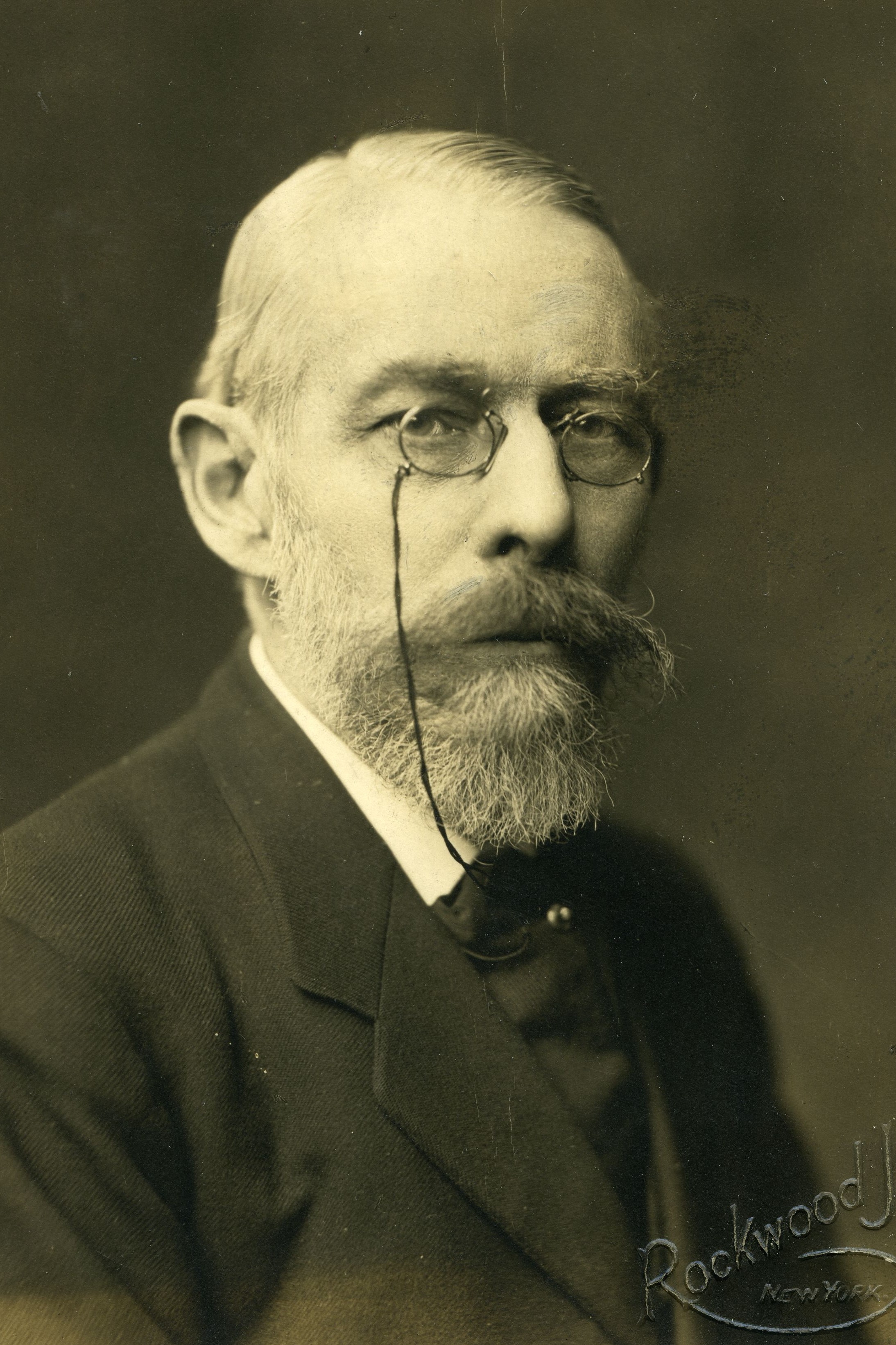

It is this genial play of humor, always as kindly as it was spontaneous, that his fellow-members will associate with Matthews. His extraordinarily wide and intimate professional acquaintance, his great vogue in foreign literary and dramatic circles, his election to the severely-exclusive Atheneum Club of London—a distinction which only three other Americans have achieved—these were only incidents of a career. But the personality which the Century will recall is that tall bent figure, hobbling on the inevitable stick, with the ragged reddish beard, the keen eyes, the low voice, and the face which was never expressionless except when Matthews reached the point of a humorous anecdote from his inexhaustible fund.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1930 Century Association Yearbook