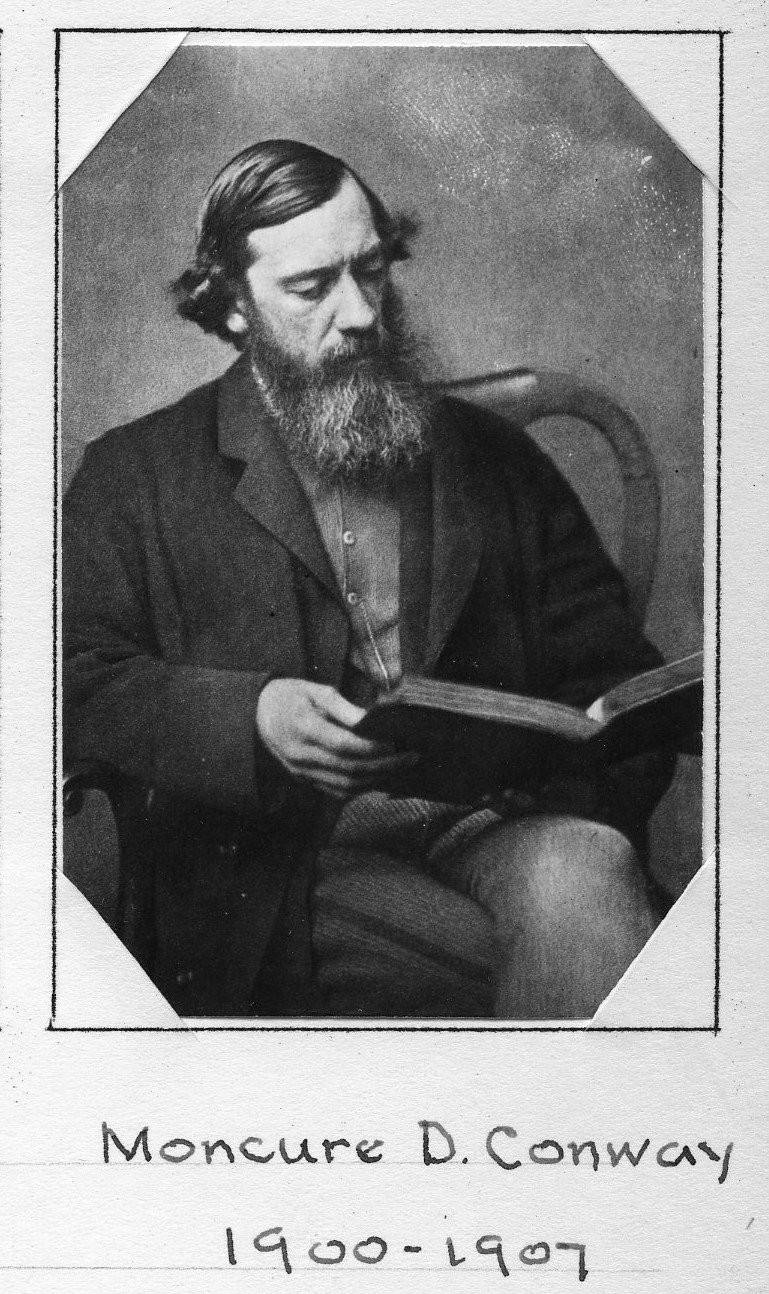

Author

Centurion, 1900–1907

Born 17 March 1832 in Stafford County, Virginia

Died 5 November 1907 in Paris, France

Buried Kensico Cemetery , Valhalla, New York

, Valhalla, New York

Proposed by Eastman Johnson and Edmund C. Stedman

Elected 1 December 1900 at age sixty-eight

Archivist’s Note: Father of Eustace Conway; elected after his son

Century Memorial

Moncure Daniel Conway was seventy-five when his full and varied life was ended. He was chosen to our membership only when age counselled rest, and entered it with the twentieth century. Born in Virginia, educated at Dickinson College, a student first of law and then of theology in two schools, he was a Southern man with Northern training, finding little rest for the sole of his foot amid the swelling waters of upheaval and convulsion in church and state during the years of his early manhood. Curious, industrious, versatile, and critical, there were few paths of belief and experience which he did not explore, and on some he walked fearlessly to the conclusions of his own logic. Many lean on inheritance and historic continuity for the test of truth and the guidance of life. Not so with Conway; he stood alone if must be, and sacrificed if necessary his very heartstrings on the altar of his personal convictions. As an apostle of liberty he found himself an abolitionist, a liberal Christian, and at last a radical. He was never without a reform on hand, his motto was that of [Daniel] O’Connell: agitate, agitate, agitate. In the South he agitated for common schools and for the freedom of the negro, abandoning his home and his birthright for the defence of a fugitive slave. With all his powers he upheld the right as he saw it in pulpit and on platform; in Great Britain he pleaded for many years the Northern cause, in season and out, with all classes of society. He was editor, exhorter, preacher, author, lecturer, traveller, and reformer; everywhere he penetrated beneath the surface and brought forth friendships and opinions which were remarkable and characteristic. He was undismayed and pronounced in his judgments of men, of politics, and of religion to the very last. Throughout his connection with us, as in other walks of life, he had the charm of originality, a grace of manner that won friends, and a sense of finality which perpetuated interest in his personality. He loathed war and loved peace, he criticised but never scoffed, he was radical but never fanatical, individual but never eccentric. The published record of his life by himself is a document of the nineteenth century.

William Milligan Sloane

1908 Century Association Yearbook