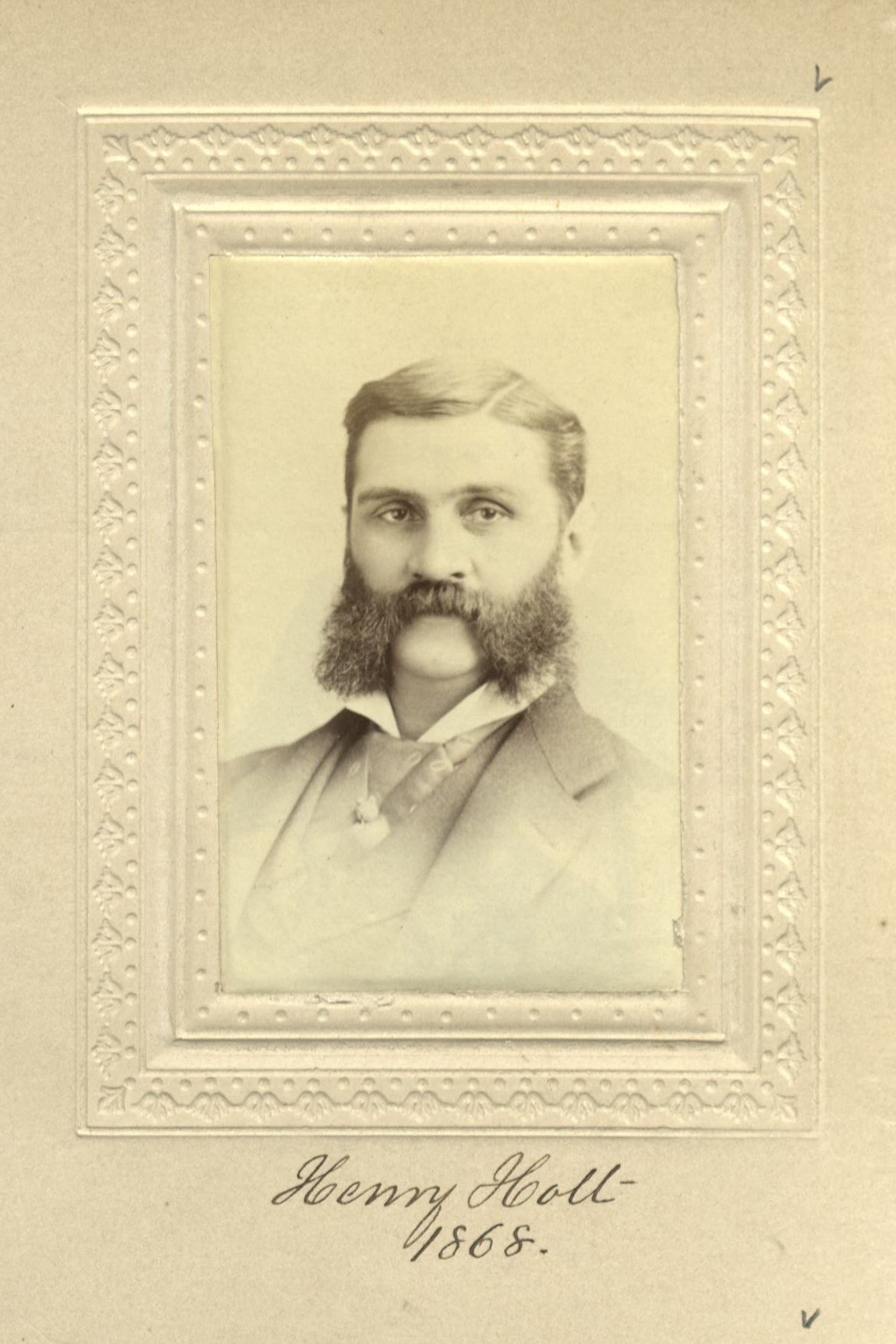

Publisher/Author

Centurion, 1868–1926

Born 3 January 1840 in Baltimore, Maryland

Died 13 February 1926 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by George P. Putnam and Henry R. Winthrop

Elected 4 April 1868 at age twenty-eight

Archivist’s Note: Brother of Charles Holt

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

- Gerome Brush

- Edward L. Burlingame

- John Jay Chapman

- Charles W. Colby

- Frederick M. Corse

- John W. Cunliffe

- Gano Dunn

- Fabian Franklin

- Franklin H. Giddings

- Daniel C. Gilman

- Abraham Jacobi

- Vernon Lyman Kellogg

- Othniel C. Marsh

- Raphael W. Pumpelly

- Herbert Putnam

- Edwin T. Rice

- W. Symmes Richardson

- Robert Livingston Schuyler

- Joseph Lindon Smith

- William G. Sumner

Supporter of:

Century Memorial

A long vista of the Century’s traditions—indeed, a long chapter of the intellectual and literary history of New York City—is presented in Henry Holt’s career. At the time of his death, his 58-year period of consecutive membership in the Century was with only one exception the longest on the active list; had he lived two months more, it would have been the longest. He was admitted to the Club in 1868, and was antedated among his living associates only by Mr. Weir’s sixty-two years. Yet he never, like some of our elder members of bygone days, lost touch with the Club because the associates of his prime were gone. A true laudator temporis acti, he could not concede that the Cenrury [sic] of his old age was quite to be measured with the group that came together, half a century before, in the rusty Fifteenth Street clubhouse. But it was true club affiliation which, up to the last, invariably directed his steps to the sociable knots in the reading-room after a monthly meeting, where the circle of younger men opened instantly to admit the white-bearded veteran with his slow and whimsical speech and his fund of anecdote, as ready then as in the seventies to match impressions on questions of the day. The impressions were well worth listening to, as every Centurion knew. The man was bound to have a richly-stored mind and memory who had begun in Civil War time to edit and publish the works of distinguished writers, who had been in close professional touch with Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, John Fiske, Edward L. Youmans and Francis A. Walker, who had turned the reading public’s attention into new literary and scientific channels at a moment when he was also meeting demand for fiction by the pioneer venture of republishing, in attractive and low-priced form, the best tales of forgotten masters of story.

The Century, however, loved Henry Holt far more for his utter originality of character than for his professional distinction. No one else looked in quite the same way as he on the ways of life and the way of living. His octogenarian memoirs are a mine of delightfully unexpected viewpoints, as naive as they are original. Even recalling his boyhood days and his narrow escape from being voted down as poet for his class at Yale, he sees that it happened “partly because I was in some respects a very disagreeable fellow.” He cannot let other people shape his habits for him. He is warned against working late at night: “In the courage of my convictions I worked all night through the ensuing winter and gained 23 pounds.” He likes tobacco, but had concluded that it was bad to use it between-meals. “Since then I have seldom smoked before dinner, but after dinner I have smoked all I wanted to; usually four or five cigars, sometimes a dozen”—a fair-sized achievement in these degenerate days. Always fond of good cheer, and recalling appreciatively “the son of the president of the American Temperance Society who said champagne had been his salvation but that he hadn’t told his father so,” the octogenarian philosopher concludes didactically that “when a man reaches the Scotch whiskey age, he’d better stick to that.” Reminded perhaps that such ideas on the conduct of life are anachronistic under the Eighteenth Amendment, he admits that his advice may come too late; yet “I don’t feel quite sure that Prohibition will last long.”

These are not the confessions of Lucullus. At the table, Holt was an ascetic. “Two of the greatest curses in my life,” he writes, “have turned out blessings,” and one of them is the fact that his thorn in the flesh, a life-long trouble with the digestive organs, had domesticated him to a Spartan diet of which he strongly approves. The other is the curse of sleeplessness, which invites his appreciative notice from the fact that “in those hours many of my nearest approaches to good thinking have been done, many of my least futile plans have been formed, and many of my least tedious passages have been written.” The picture is appealing for its very oddities; not least so in a man whose robust personal character faced the larger troubles of life with an uprightness and rectitude that endeared him even to other men whose convictions he rejected.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1927 Century Association Yearbook