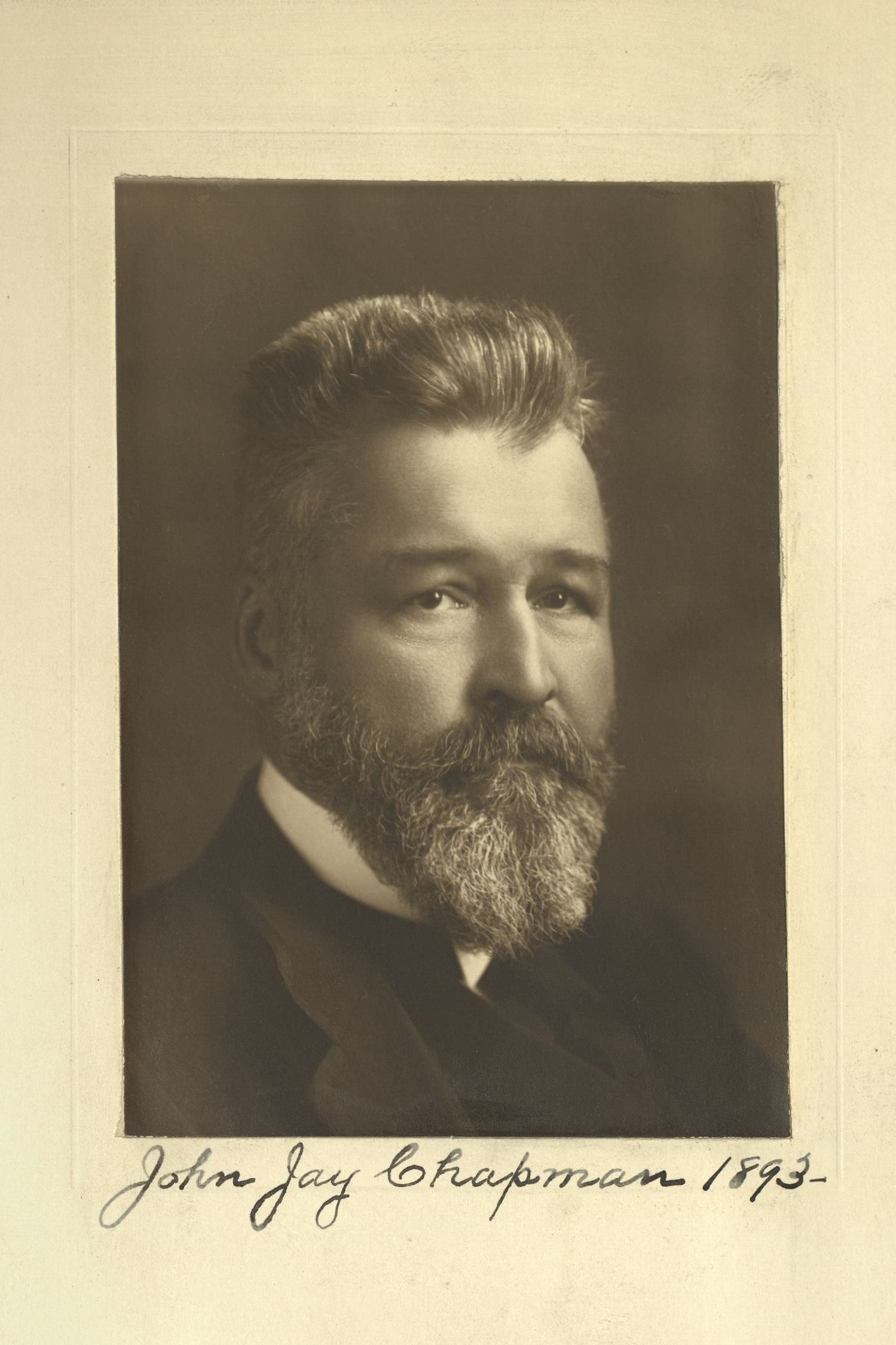

Lawyer/Writer/Poet

Centurion, 1893–1933

Born 2 March 1862 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 4 November 1933 in Poughkeepsie, New York

Buried Saint Matthew’s Episcopal Churchyard , Bedford, New York

, Bedford, New York

Proposed by Edmund R. Robinson, Henry Holt, and Gustav H. Schwab

Elected 3 June 1893 at age thirty-one

Archivist’s Note: Grandson of John Jay; nephew of William Jay, Edmund R. Robinson (his proposer), and William H. Schieffelin; cousin of William J. Schieffelin; father of Conrad Chapman

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

Fellow-Clubmen were apt to meet John Jay Chapman in the library, where the stout and slightly stooping figure, the earnest face, the half-read book tucked under the maimed left arm while the right hand filled a pipe from the deftly-poised tobacco-pouch, will always belong to memories of the place. If Chapman had lived in the Eighteenth century, his writings might have had a part in directing public opinion. Politics and economics did not interest him as they interested that period’s essayists and pamphleteers; but Chapman’s intensity of feeling, when applied to his own topics, was quite as great as theirs, and he easily matched them in mastery of style or originality of view. The constant unexpectedness of Chapman’s critical judgments was a delight. They were so attractively presented that even a doubting reader found himself, for the moment at any rate, assenting reluctantly. But Chapman had to divide his audience with the newspaper editorials and the radio broadcasts—which is one reason why his published judgments were read by an appreciative few. Even with them, it was mostly Chapman’s own personality which interested; perhaps because it puzzled. The London Times discovered in him a “combination of New York’s cosmopolitan liveliness with all those long-suffering New England pieties.” But that hardly draws the picture. The flavor of Chapman’s judgments and descriptions is really created by his mixture of frequently unsparing denunciation with the kindest possible feeling for the culprits.

Celebrities of past centuries received from him much the same treatment as distinguished contemporaries. That Dante appealed to his personal sympathies was plainly indicated by Chapman’s own description of the poet as “terrible in the Italian sense; that is to say, outspoken in the extreme.” Chapman’s English rendering of some passages from the “Commedia” reproduces the spirit of his poet as has been done by few translators. But he does not hesitate to dismiss as altogether untrustworthy Dante’s assignment of historic personages to their place in the hereafter. “Any endeavor,” so he thinks, “to bring these fancies into accurate relation with theology or history is fantastic.” Whether this verdict should apply to Dante’s reservation of a place in his Inferno for the French king who reduced the gold content of the currency unit, Chapman was probably not economist enough to discover. He gives place to nobody in appreciating Shakespeare; whose writings, he agrees, “touch on our life and mind at all points” and are “behind most of our critical perceptions.” Nevertheless, “although the world, after three centuries, goes on being fascinated by ‘Othello,’” it is “an odious play, false to life and without overtones.” “There never was a man like Macbeth, and there never could be.” Hamlet is “a philosophic gimcrack,” with “the mind of an elderly man set on the shoulders of a boy of eighteen and turned loose in a tragic situation.” Shakespeare and Dante would have argued out these things with Chapman; but Chapman would have held his ground, and both of them would have liked him all the better for it.

With his own contemporaries, Chapman applied his critical method joyously. Bernard Shaw is “a very powerful and remarkable being”; he has rediscovered some of the “psychological secrets of art” and has “revolutionized English acting.” But Shaw “does not know that there are things which cannot be made funny.” His popular success indicates the public’s appetite for “mustard at every course”; his plays are acclaimed because “we like the butter to be a little rancid” and because, to the audience of the day, humor “seems flat unless it contains just a little tang of doubt as to the fundamental truth of virtue and honor.” The strongest of all Chapman’s prepossessions—his ideas on the higher education of today—brings him in touch with developments at his own Alma Mater. True to his spirit of controversial sportsmanship, Chapman describes President Eliot as “sincere and spontaneous,” praises his capacity to “get things done,” and emphasizes Eliot’s “clairvoyance in the matter of character.” But he forthwith proceeds to explain that for Eliot “no ideals except ideals of conduct had reality,” that “literature and philosophy were names of things in bottles.” Higher education in fact has nowadays “almost no friends, no champion, no spokesman.” “The college degree in America, like the French assignat and the German mark, has become something to get away from.”

No one but Chapman could have written exactly this. If another man had done so, he would promptly be classified as pessimist or ranter. But with Chapman, controversial outbursts merely bring into stronger light his underlying good humor and his complete originality. His nature was essentially hopeful, his view of life not in the least unpleasant. Whoever came to know him personally found him kindly, non-contentious, quite as interested in the ideas of others as in his own. With such a club associate, conversation across the table was bound to be illuminating. It might be said, in line with the remark once made regarding another man of strong opinions, that it was intellectually more profitable and delightful to talk with Chapman and disagree with him than to agree with any one else.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1934 Century Association Yearbook