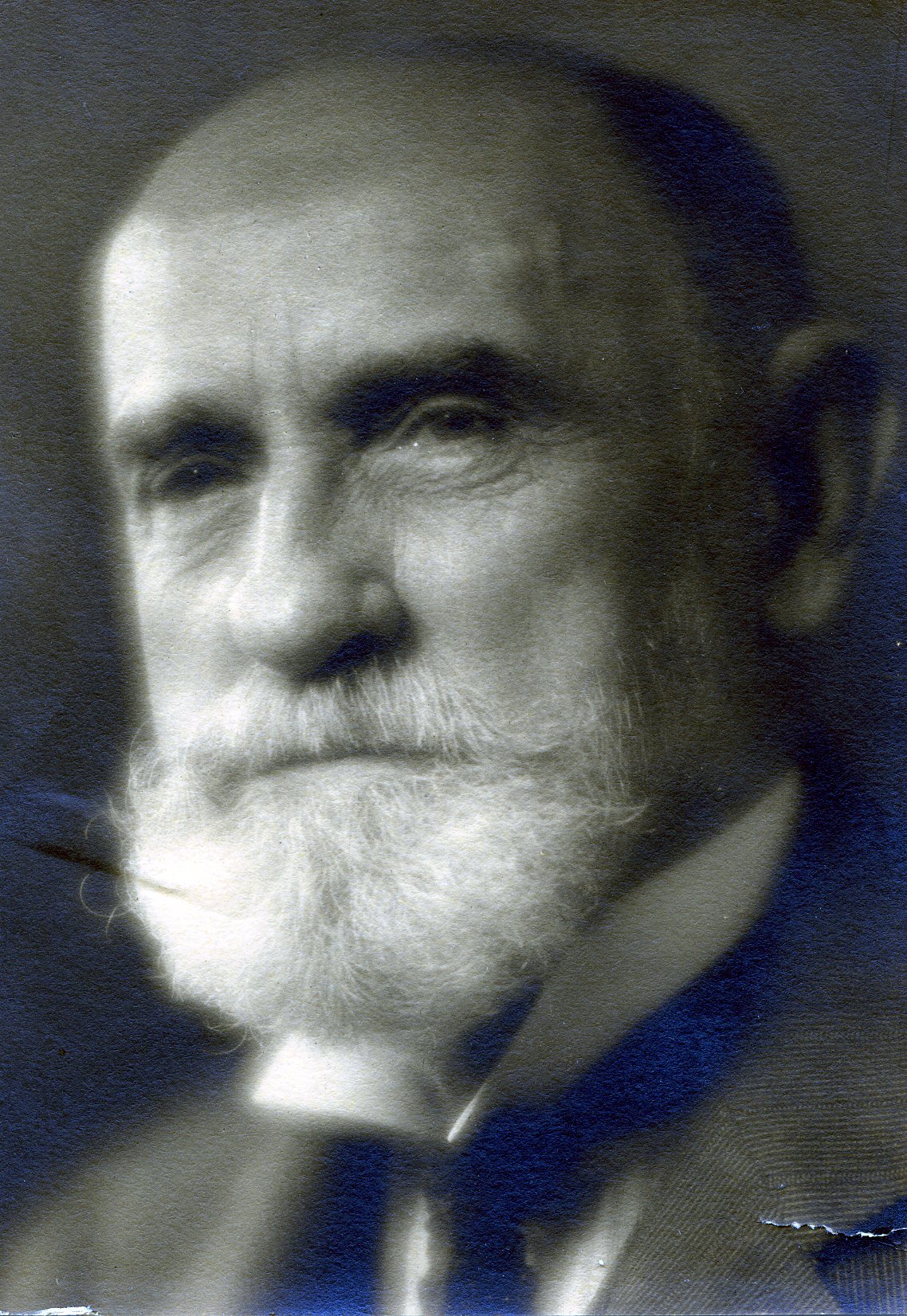

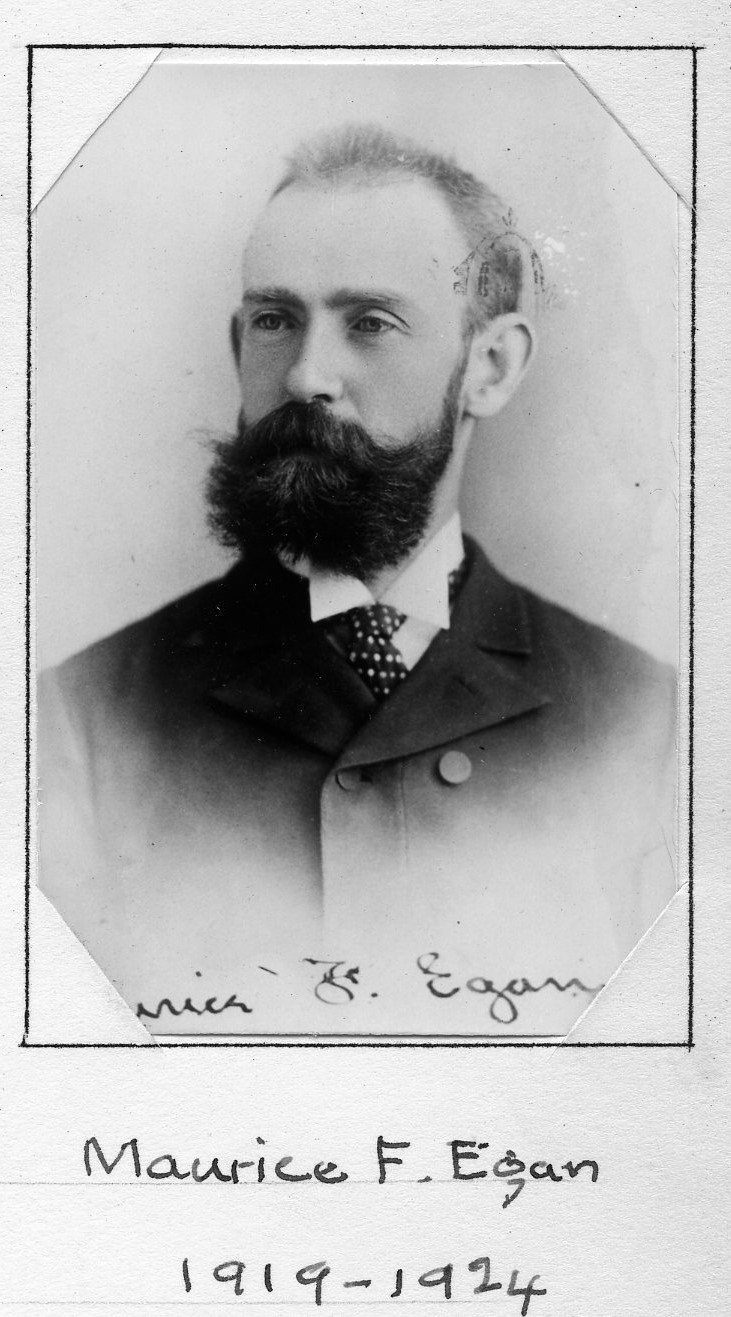

Man of Letters

Centurion, 1919–1924

Born 24 May 1852 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Died 15 January 1924 in New York (Brooklyn), New York

Buried Old Cathedral Cemetery , Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Proposed by Robert Underwood Johnson and Henry van Dyke

Elected 6 December 1919 at age sixty-seven

Century Memorial

That the Century’s representation in the field of American diplomacy, past and present, should have been exceptionally large, is a natural result of the American government’s fortunate tradition of selecting for its envoys at important foreign posts men of culture, of social quality, of literary rather than political training. In older days and in somewhat critical diplomatic circumstances, two of the former presidents of the Club [George Bancroft and Elihu Root] represented the United States with brilliant success at the most important European courts. A long list of other ministers and ambassadors is contained in our roll of members past. The minister to Belgium during the German invasion [Brand Whitlock] and the two Ambassadors to Italy [Thomas Nelson Page and Robert Underwood Johnson], during the war and during the post-war reconstruction, are on our roll of living members [sic: Page had died in 1922]. In personality and achievement, Maurice Francis Egan held high place in this notable company.

Previously known to the public only as a prolific author, a trenchant critic and a teacher of English literature, Egan became our minister to Denmark in the Roosevelt administration, retaining his post through the administrations of Taft and Wilson. In the somewhat provincial atmosphere of Copenhagen, he was able instantly to acquire that intimate place in the inner diplomatic circle which fell to John Quincy Adams at the Russian court of the first Alexander and to John Bigelow at the unostentatious court of Prussia, before the old king had been promoted Emperor. The time came when the Danish government’s perfect confidence in Egan, a result of his genial manners, strict integrity, wide acquaintance and sturdy common sense, was of the highest service to the United States. Placed on the very threshold of a threatening Germany, it was through his patient, wise and tactful effort that Denmark’s three Caribbean islands, which Captain Mahan had described as including “one of the great strategic points in the West Indies,” whose proposed cession had for fifty years been a sore spot in diplomacy and on which the German government had long cast covetous eyes, were peacefully transferred to the government at Washington.

Even before the war, and far more positively after 1914, Egan was impressed with the necessity of acquiring for our Government this potential Heligoland, confronting Cuba, Porto Rico and Florida. The task was difficult. The people of the islands had indeed voted approval of the purchase many years ago, but Denmark had its own colonial pride and a smouldering mutual resentment had been left by our Senate’s refusal, after long delay, to approve the purchase treaty of 1868 which our own government had proposed and by the blocking, through a majority of one in the Danish parliament, of the similar treaty of 1902. Convinced in 1916 that the United States would be at war with Germany within a year, Egan again approached the Danish foreign minister. The conversation might have been a dialogue from Dumas: “Excellency, will you sell your West Indian Islands?” “It will require some courage.” “Nobody doubts your courage.” “The susceptibilities of our neighbor in the South—” “Let us risk offending any susceptibilities.” “You will never pay the price.” “My country is more generous even than she is rich; the transaction must be completed before—”. And the islands became American possessions, after a payment twice as large as Seward had conceded in 1867.

But Egan’s Danish mission was not always a bed of roses. It may be doubted whether even the checkmating of German war-time intrigue was quite as arduous a task as the awkward official duty which befell him when Henry Ford’s “peace ship” anchored at Copenhagen with its cargo of quarrelsome enthusiasts and bewildered philanthropists, on their way to Berlin to persuade the German emperor to withdraw his armies from the trenches in the face of the enemy. Probably Egan was helped out on that occasion by his abundant sense of humor. But humor could not help him out when Doctor Cook arrived in 1909 at Elsinore and was welcomed by official Denmark as the discoverer of the North Pole.

Egan’s account of his experiences in that extraordinary affair betrays a mixture of reminiscent amusement and reminiscent mortification. The Danish court was heaping laurel-wreaths on Cook; the Danish University was conferring degrees. Exactly how could the American minister to Copenhagen, Cook’s compatriot, throw cold water on those ceremonies? “All that I knew,’’ Egan wrote, “was that he had been the associate of Admiral Peary, lived in Brooklyn, and was a member of very good clubs; the only indication that made me suspect that Dr. Cook was not scientific was that he spoke most kindly of all his—may I say it?—step-brother scientists.” Besides, Egan insisted in his latest apologia for the episode, “the coming of Dr. Cook was a godsend to the Danish government, which was approaching a political crisis; the Cook controversy made such a diversion that the question between those who wanted to defend Denmark and those who were unwilling to spend more money for forts on the German side, was almost forgotten.” But Egan also confessed to admiring envy of the deftness with which another public man slipped out of the dilemma, when President Taft “merely answered Dr. Cook’s telegram of announcement by congratulating him on his ‘statement’ that he had discovered the North Pole.”

Alexander Dana Noyes

1925 Century Association Yearbook