Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

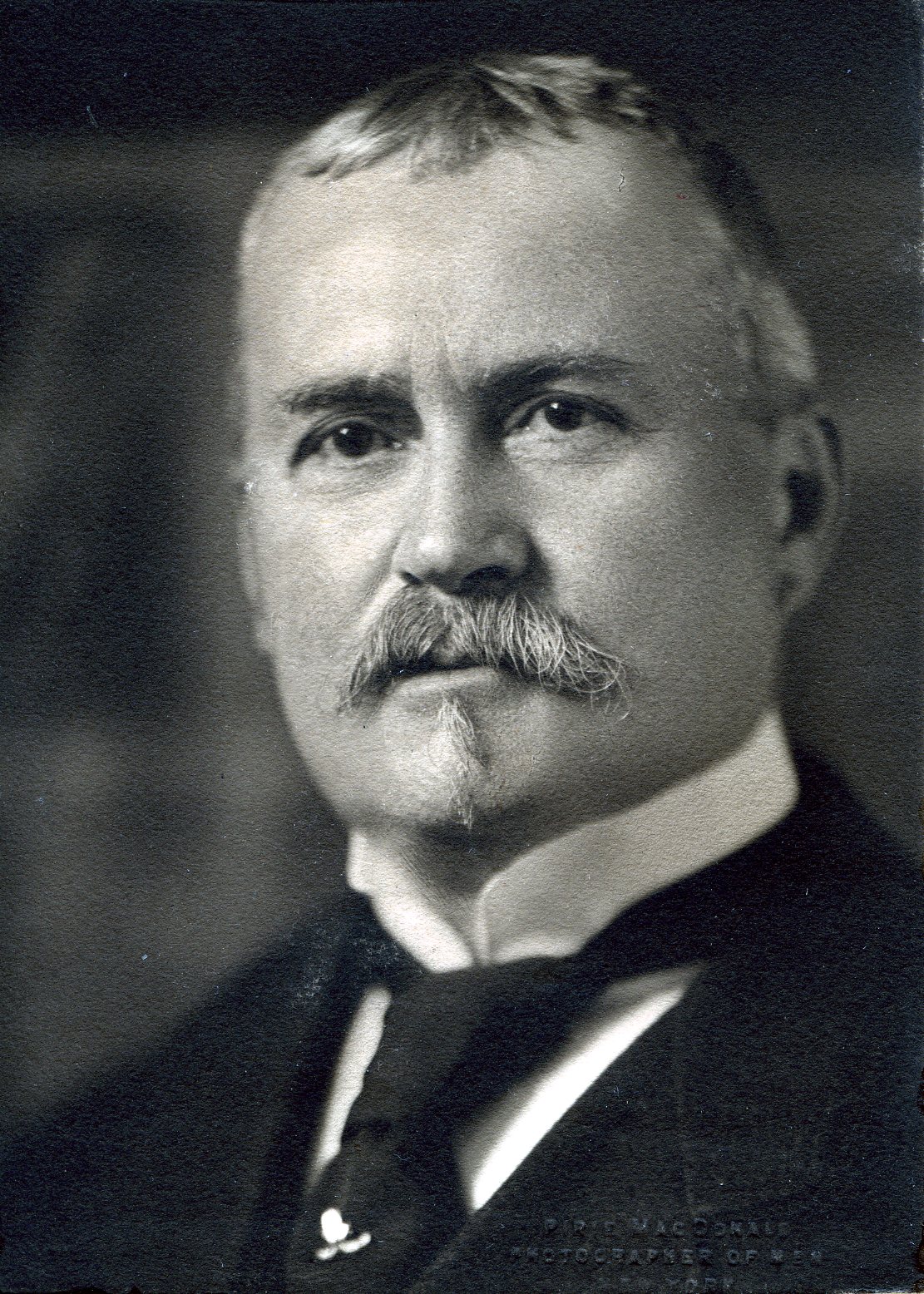

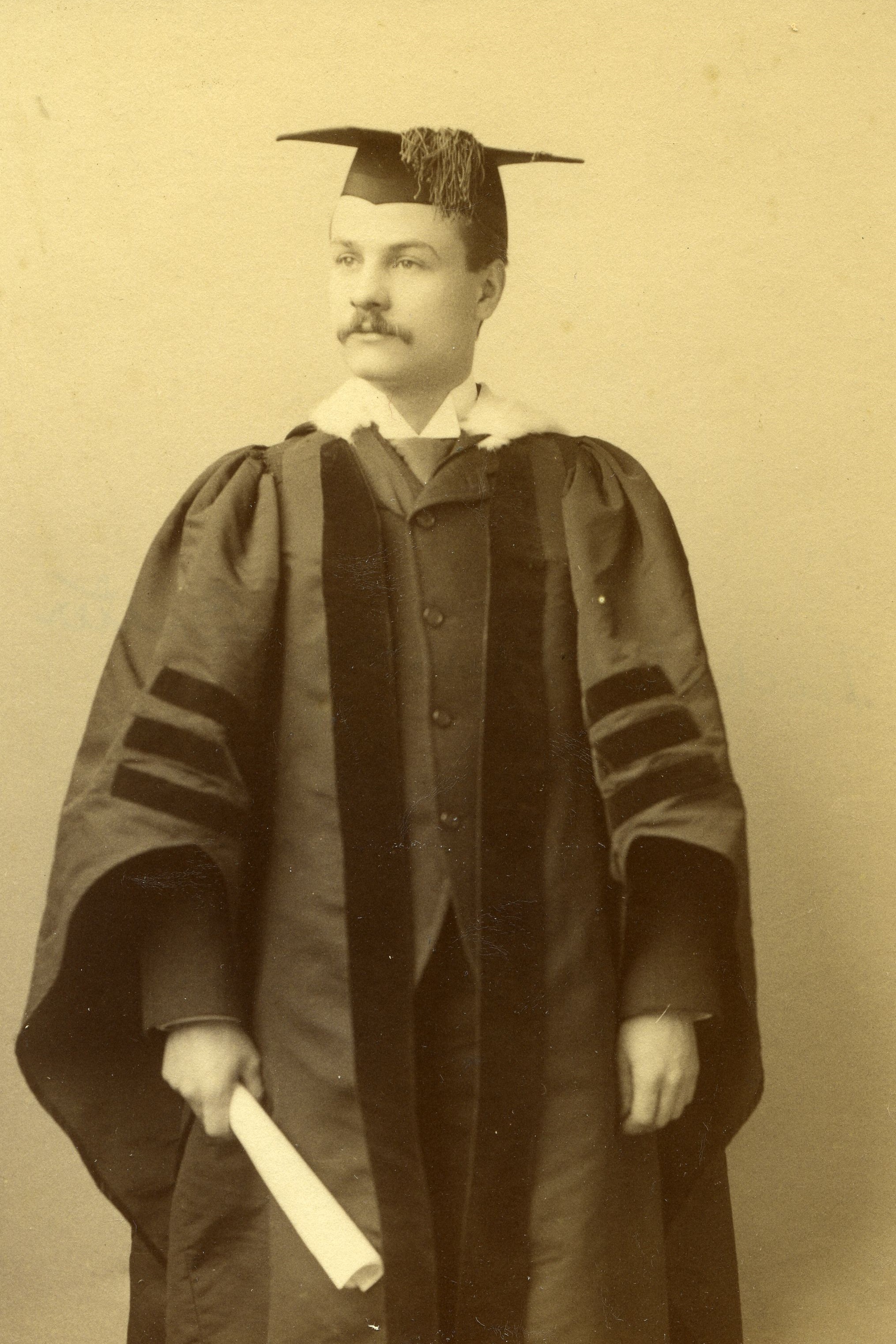

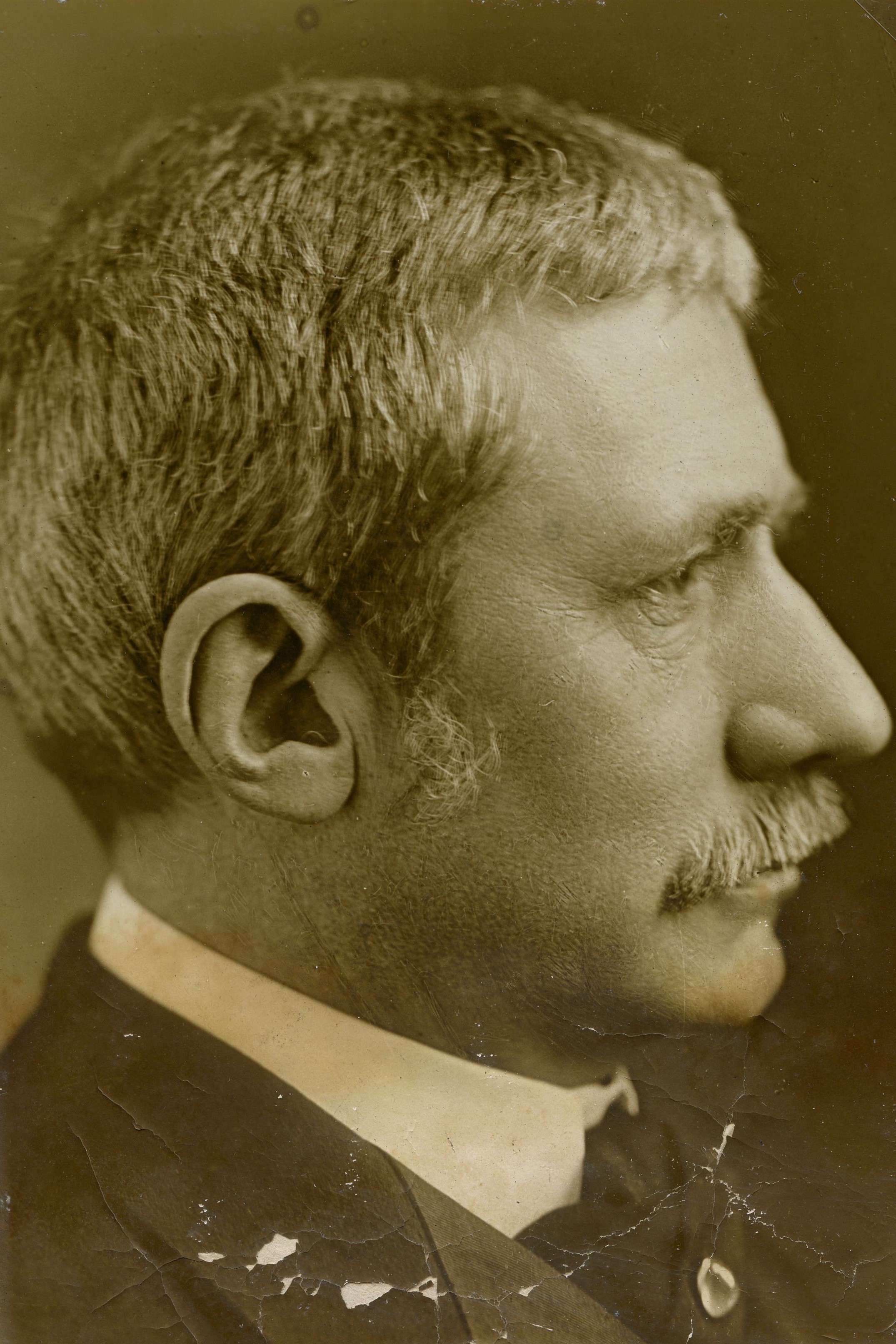

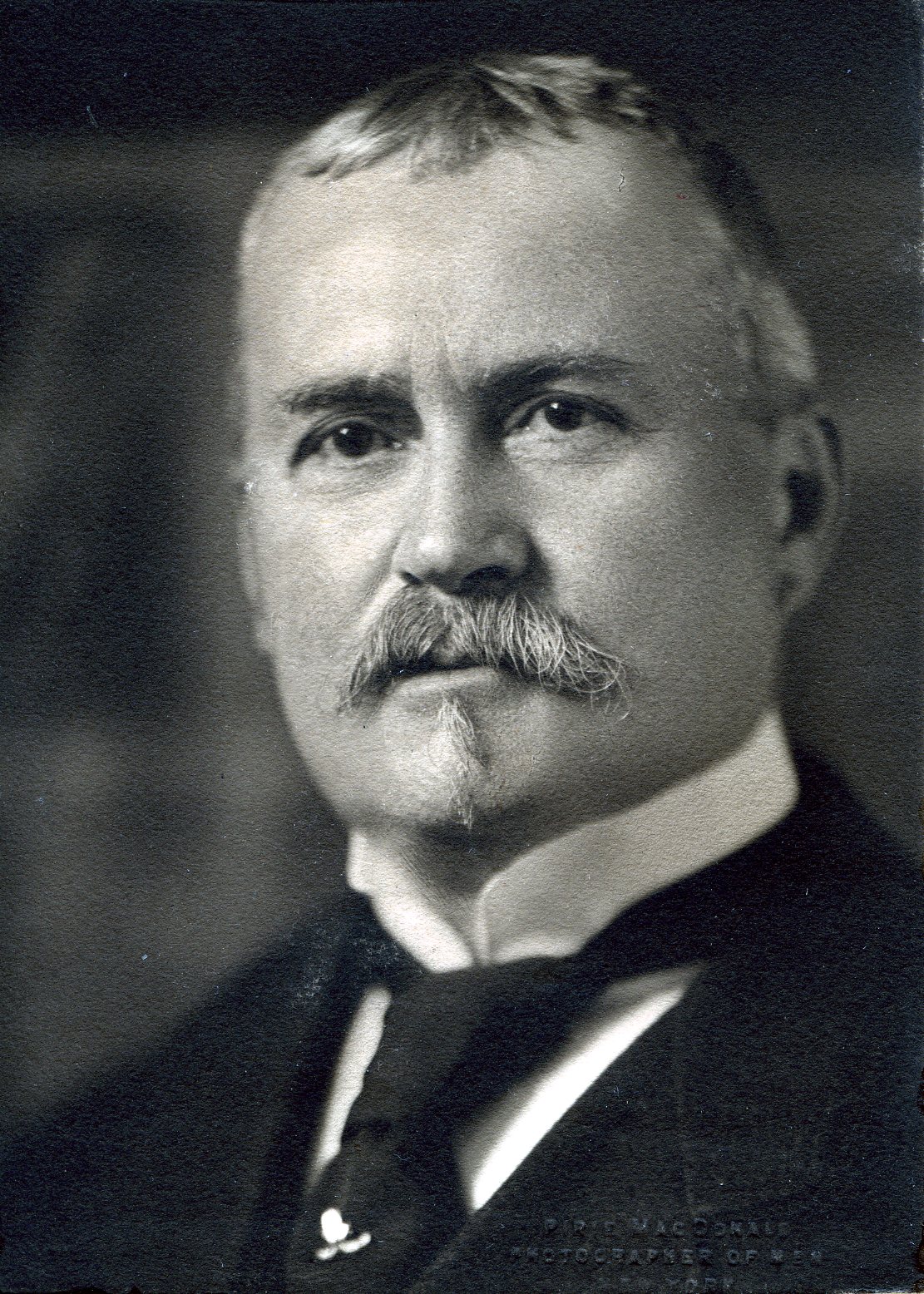

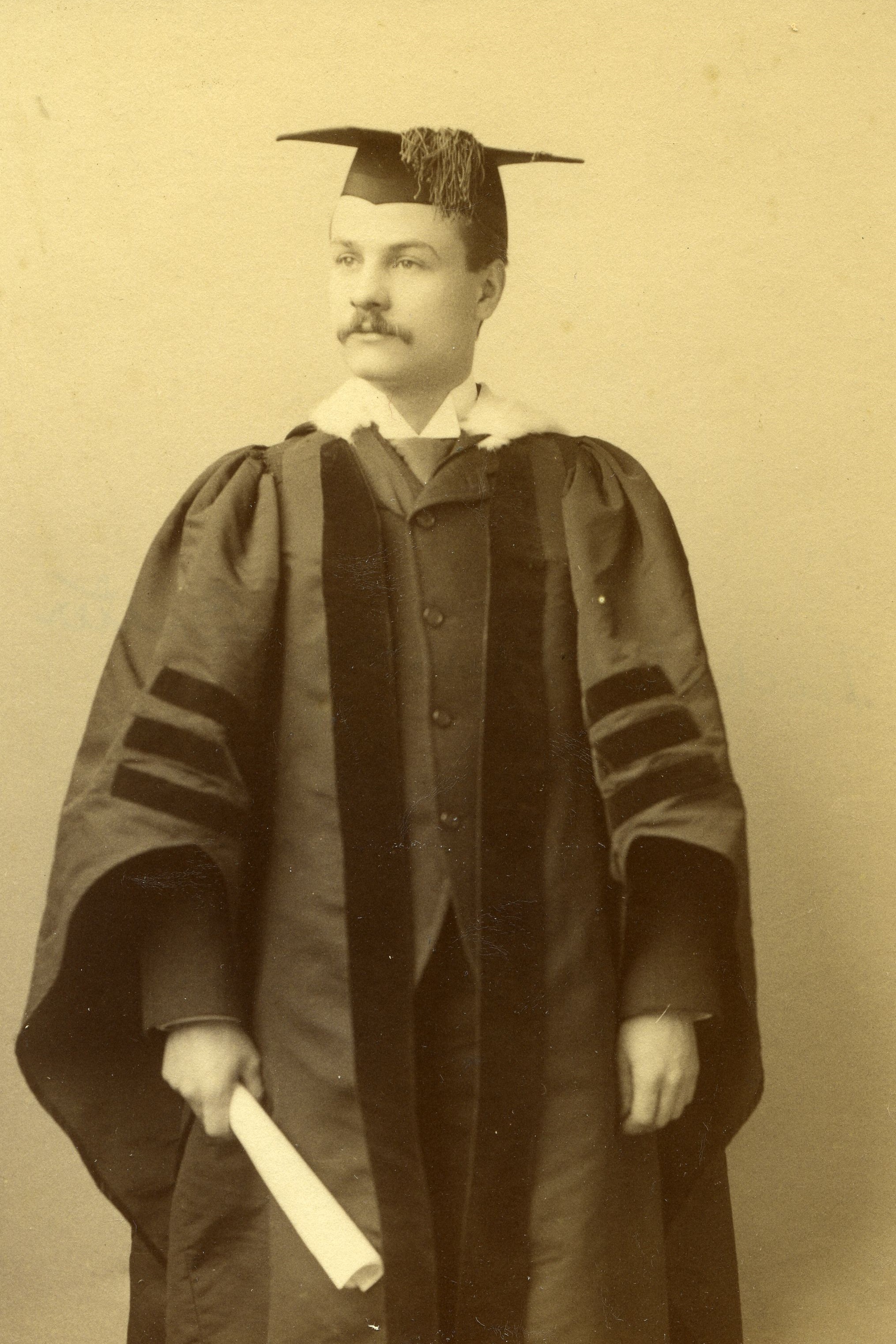

Elihu Root

Secretary of State/Secretary of War/U.S. Senator

Centurion, 1886–1937

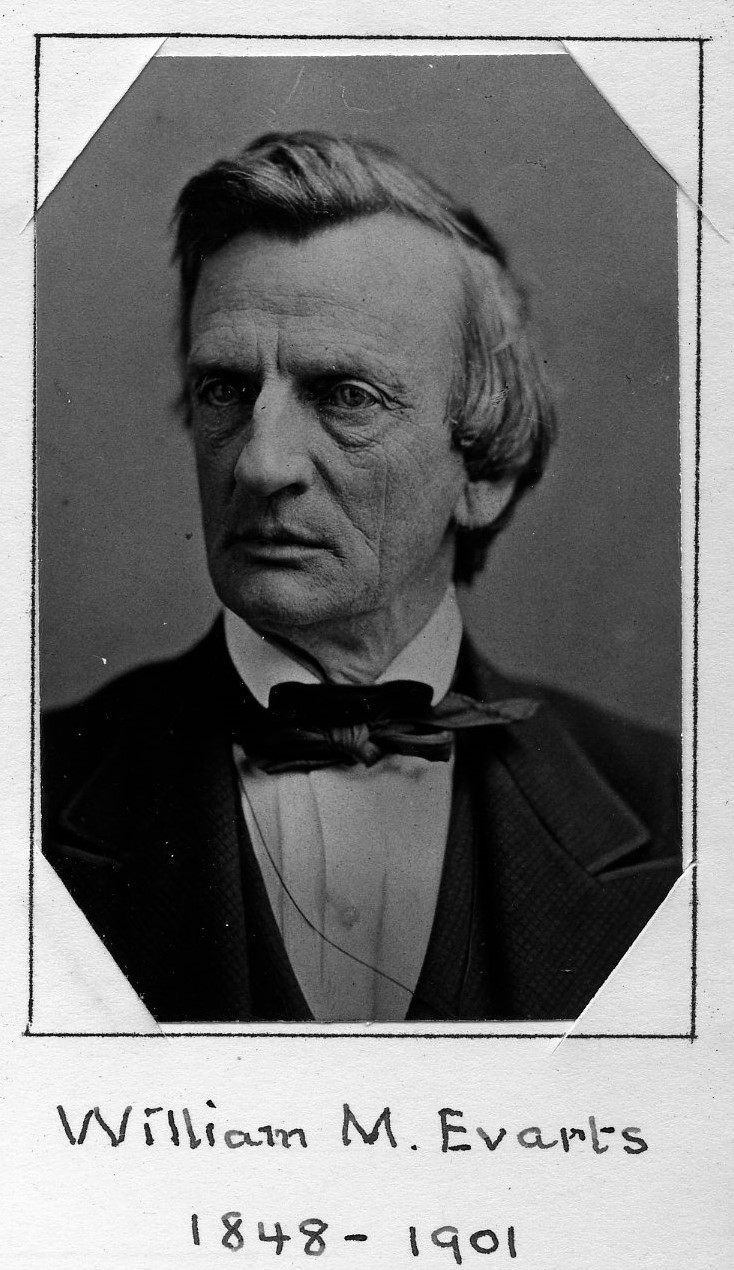

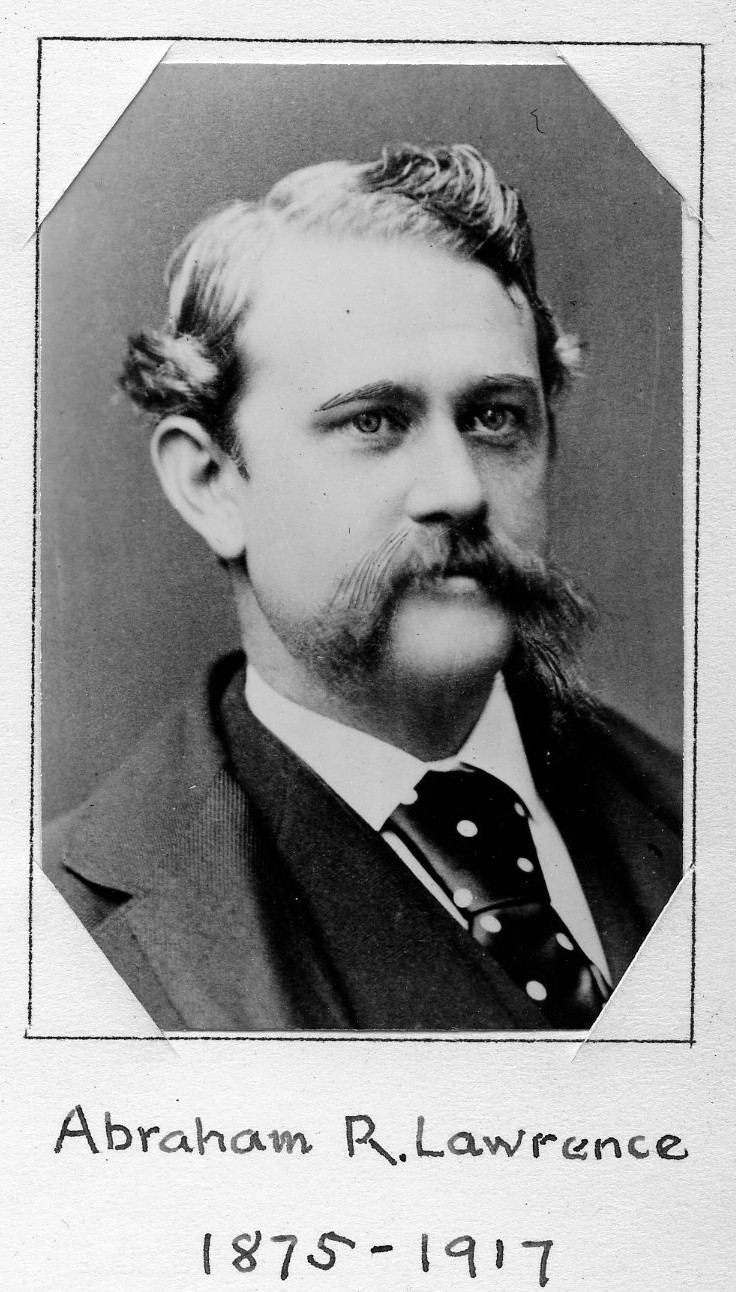

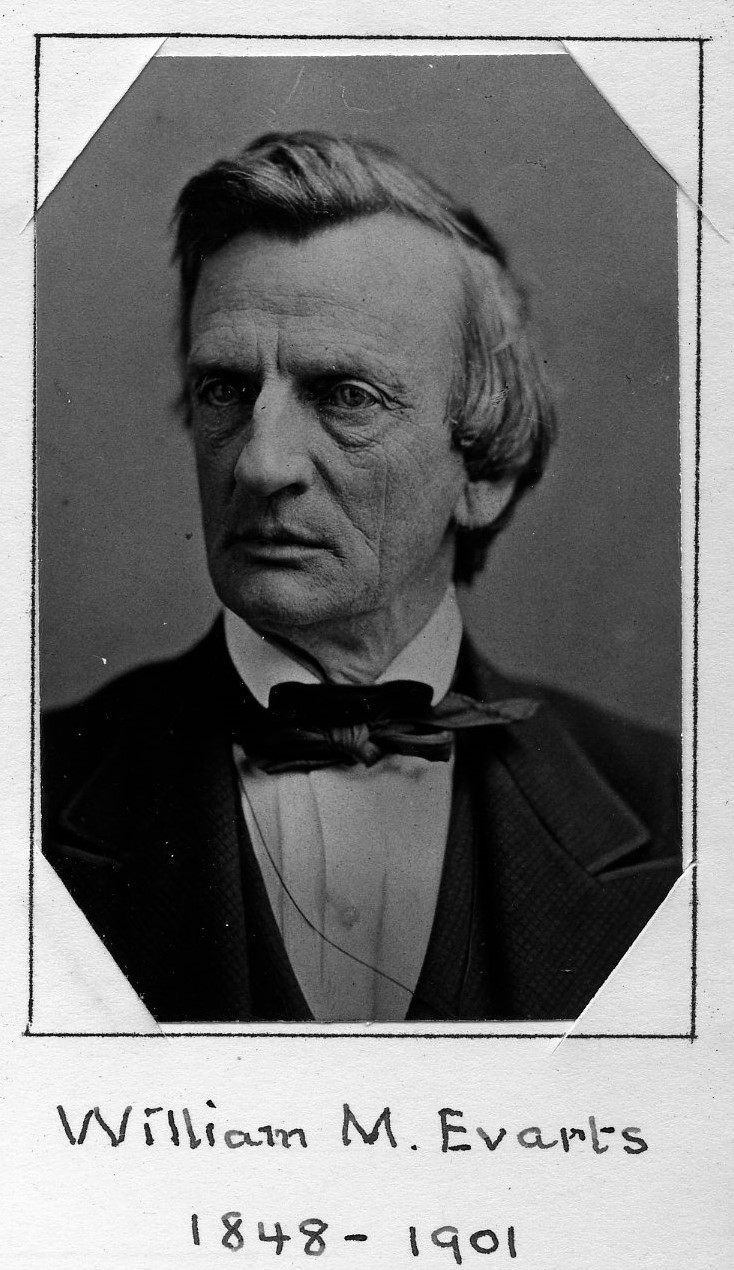

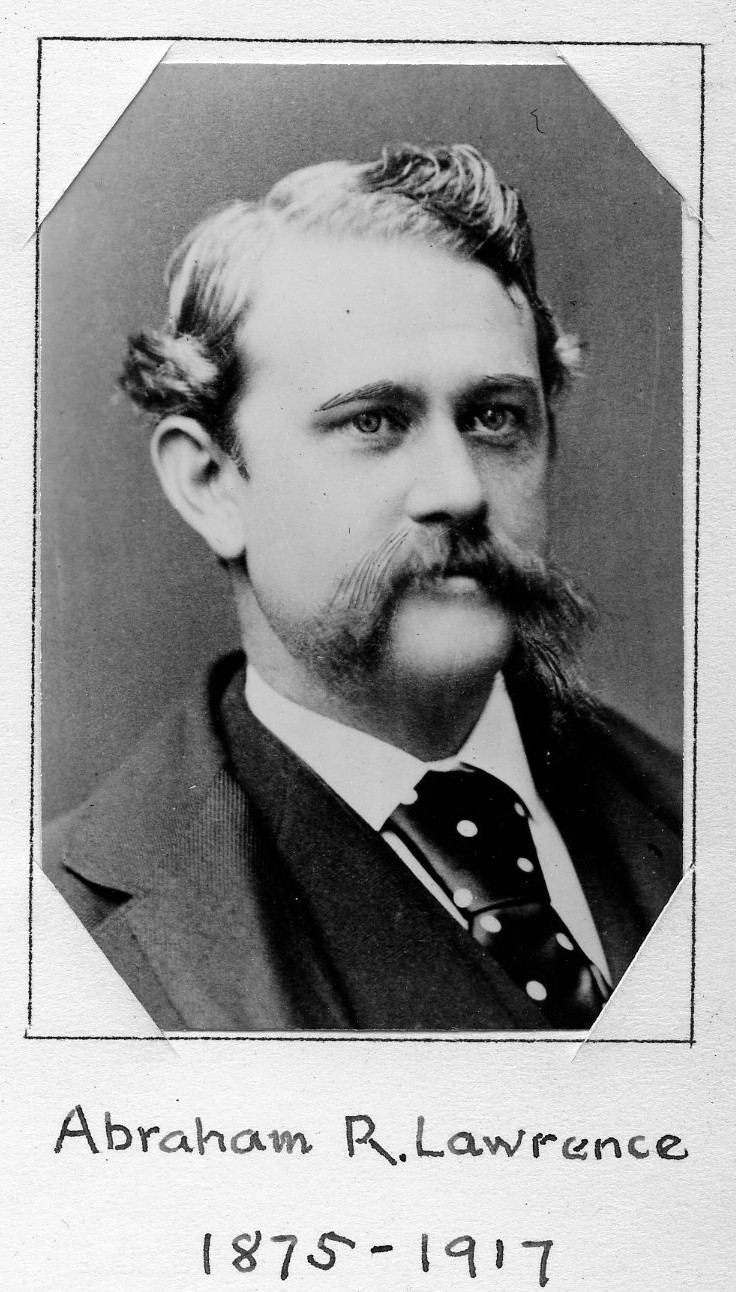

William M. Evarts and Abraham R. Lawrence

Clinton, New York

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age forty-one

Clinton, New York

Archivist’s Notes

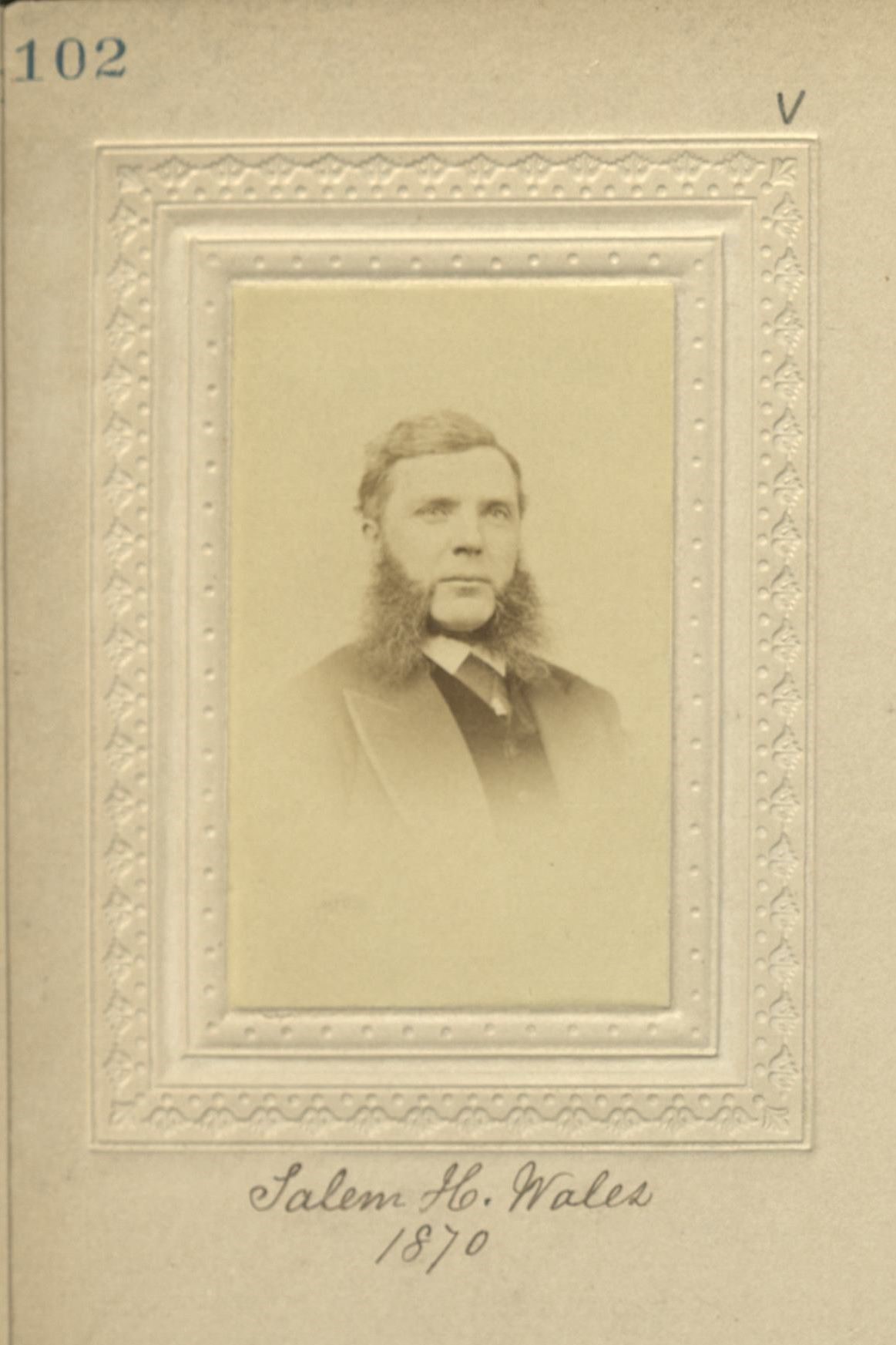

President of the Century Association, 1918–1927; designated an honorary member in 1928. Father of Edward W. Root and Elihu Root Jr.; son-in-law of Salem H. Wales; father-in-law of Ulysses Simpson Grant III. His presidential remarks at the Century’s seventy-fifth anniversary commemoration in 1922 may be viewed at Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Century Association.

Available Digital Resources

Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Century Association

After his death, a series of memorial addresses delivered at the clubhouse by Nicholas Murray Butler, Royal Cortissoz, and Henry L. Stimson was published as Elihu Root, President of the Century Association 1918 to 1927: Addresses Made in His Honor at the Clubhouse, April 27, 1937.

Century Memorials

The high place occupied by Elihu Root, not only in his profession and in the conducting of public institutions but in the national government at Washington, was forcefully described at the Century’s memorial meeting last April. The speeches on that occasion by Dr. Butler and Colonel Stimson, the letter from Mr. Newton Baker, testified to what Root’s army reorganization meant in our subsequent effort during war, and to the deep impression made on our foreign relations by his three-and-a-half years as Secretary of State under Theodore Roosevelt. It was recalled also how our national legislation was affected when he served for six years as United States Senator from New York; our state and civic framework when he sat in the New York State Constitutional Convention, and the nation’s view of its own fundamental problems when, advanced in years and retired from public activities, Root talked or wrote as an Elder Statesman to whom everybody listened.

All this the Century knew. In it, the Club of which he was for ten years President took individual pride. Yet the picture of Root which his fellow-members will retain is not primarily that of diplomatist and statesman, but of an intimate Club associate who was always in the chair at monthly meetings and who invariably lent to the occasion an atmosphere of mingled efficiency, dignity and humor. President Cortissoz, speaking at the April memorial gathering, touched on these qualities. He properly recalled Root’s response to Wickersham, who had asked him how, with his multifarious engagements, he managed always to be present at scheduled monthly meetings of the Club or its Managing Board. Root quietly replied that, when he was elected President of the Century, he reserved to the Club, in his memorandum-book for a coming year, every date on which either of those occasions fell. He remarked, as even the punctilious Wickersham somewhat wonderingly recalled, that the question arising when named for such an office was not whether to accept it as a distinction requiring only actual service if convenient, but whether to accept at all unless the way was clear for performing every duty of the place and being present at every stipulated date. That Root was exceptionally equipped as chairman of a meeting, great or small, every one knew from his political achievement—notably his conducting of the tumultuous Republican National Convention in 1912. But no Centurion will have forgotten the quickness with which the Club’s monthly business was dispatched by him or, particularly, the Chairman’s handling of Club discussion. Necessarily, many of the speakers for or against a motion were to the chairman personally unknown. But Root never inquired of a fellow-officer what was the member’s name; he recognized him in a sympathetic manner which somehow invariably convinced the Centurion who had risen, that the chairman knew him and was interested in what he had to say.

Perhaps the Board of Management of his day will still more vividly remember Root the dinner-table companion. His easy conversation, subtle humor, store of reminiscence will not soon be forgotten by his colleagues. He had a way, peculiar to himself, of giving a wholly unexpected turn to conversation. Eleven years ago, when Root privately made known his purpose of resigning from the Century’s presidency, after a shorter term than many of his predecessors, one of his fellow-officers remonstrated. Root replied, “I have served already longer than Choate or Bigelow.” His companion protested: “That is no fair criterion. Both of those Century presidents died in office.” “Well, of course,” Root rejoined, reflectively, “there is that avenue of escape.” In the casual talk of Board meetings, Root’s judicious but never arrogant expression of opinion—usually stated after every one else at the table had spoken—seemed to belong altogether to his personality. Of Al Smith, notwithstanding their opposite political affiliations, he was an outspoken admirer; he had watched and met the New York Democrat when a State Constitutional Convention was wrestling with complicated public problems. Root placed Al Smith far in the forefront of men whose intellectual honesty and political capacity were important to the country. His judgments were not always thus indulgent. When the Board meeting happened to fall on the day of William J. Bryan’s death, individual impressions of Bryan’s career and personality had been declared by most of the diners; after which, all of them looked at Root inquiringly. Root paused for a moment, shook back his hair with a characteristic gesture, then remarked, quietly: “Well, gentlemen, I have seen much of Mr. Bryan, and I consider him one of the most ignorant public men that I have ever met.”

What Elihu Root thought of the Century was shown not only by his frequent presence in the dining room, or by the fact that his membership had been third longest on our resident list, or by his tribute to the Club’s past history at its seventy-fifth anniversary, but by the striking fact that, even in his latest years, he invariably came in person to the Club to select the cigars which he always sent at Christmas-time to his fellow-trustees at Hamilton. It is a personality which will be long and affectionately remembered; not less so, certainly, in that Root will remain hereafter a part of our national history. Root was a League-of-Nations adherent. If, as was at one time Washington rumor when the war ended and the Versailles conference had been called, Wilson had asked Elihu Root to serve as member of the American delegation and to participate in discussing terms of peace with the wily and seasoned European diplomats, the course of contemporary history might have been different.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1938 Century Association Yearbook

Root was born in Clinton, New York, where his father was a professor at Hamilton College. At age 19, Elihu graduated first in his class at Hamilton before graduating from the NYU School of Law in 1867. Root married Clara Frances Wales and they had three children: Edith, who married Ulysses S. Grant III; Elihu Root, Jr.; and Edward W. Root.

After 30 years in private practice, he was appointed Secretary of War by McKinley in 1899, serving till 1904 under McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. He was concerned about the new territories acquired after the Spanish-American War and worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans. He wrote the charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the U.S. from Puerto Rico. Henry L. Stimson, himself a later Secretary of War, said of Root, “no such intelligent, constructive, and vital force had occupied that post in American history.”

In 1905, President Roosevelt named Root to be the Secretary of State after the death of John Hay. On a tour to Latin America in 1906, Root persuaded those governments to participate in the Hague Peace Conference. He worked with Japan to establish the Root-Takahira Agreement, which limited Japanese and American naval fortifications in the Pacific.

Root served a term in the Senate from 1909 to 1915. In June 1916, he was drafted for the Republican presidential nomination but declined, stating that he was too old to bear the burden of the Presidency. The nomination went to Charles Evans Hughes, who lost the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Root’s initiatives are remarkable. He helped create the Permanent Court of International Justice; he was the founding chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations; he was the first president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; he helped found the American Society of International Law; he was among the founders of the American Law Institute; and he also helped create the Hague Academy of International Law. In 1912, Root received the Nobel Peace Prize.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

Edwin BaldwinLawyerCenturion, 1907–1926

Edwin BaldwinLawyerCenturion, 1907–1926 -

Francis Marion BurdickProfessor, Columbia Law SchoolCenturion, 1897–1920

Francis Marion BurdickProfessor, Columbia Law SchoolCenturion, 1897–1920 -

Nicholas Murray ButlerEducator/DiplomatCenturion, 1890–1947

Nicholas Murray ButlerEducator/DiplomatCenturion, 1890–1947 -

William M. EvartsLawyer/Public ServantCenturion, 1848–1901

William M. EvartsLawyer/Public ServantCenturion, 1848–1901 -

Abraham R. LawrenceJudgeCenturion, 1875–1917

Abraham R. LawrenceJudgeCenturion, 1875–1917 -

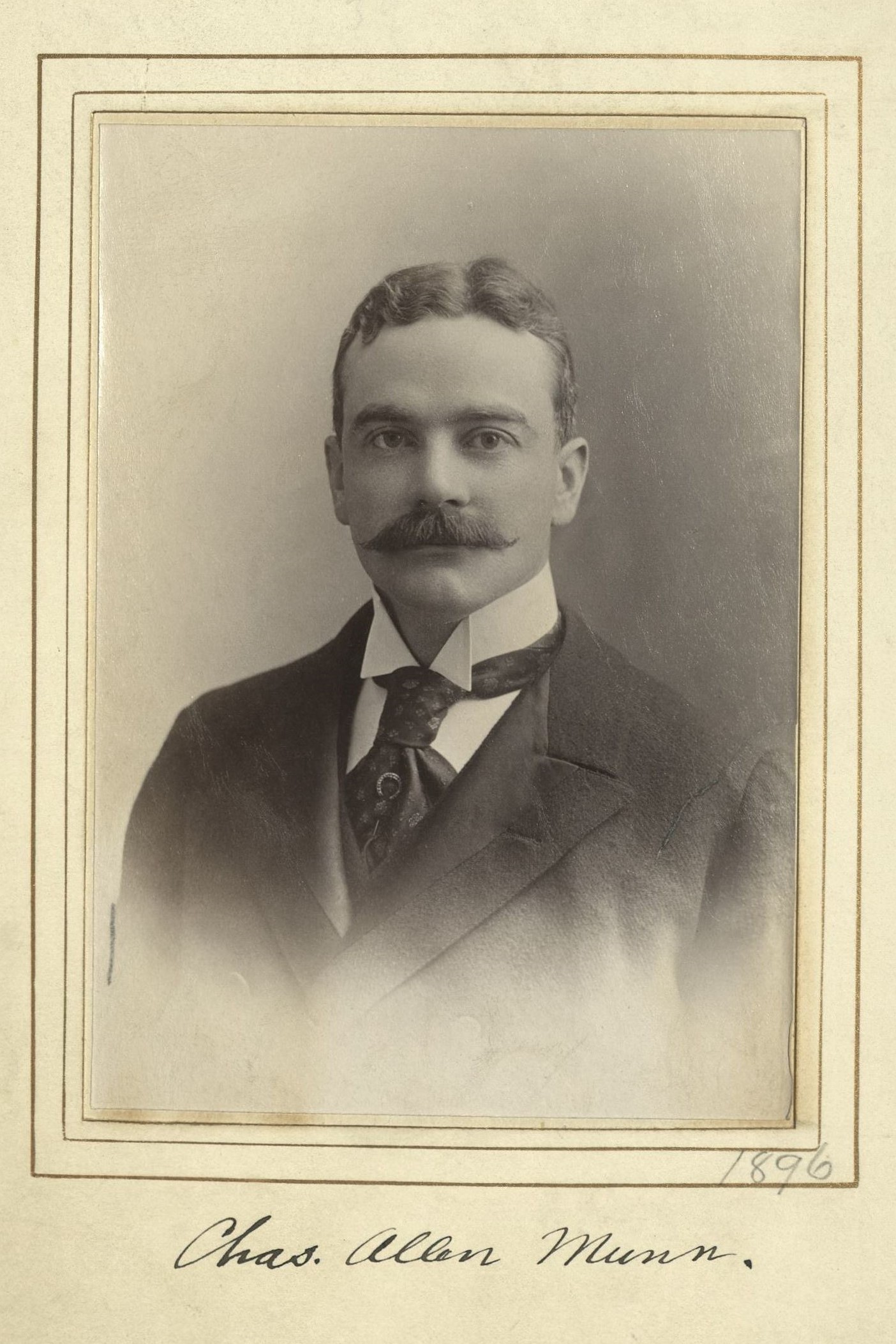

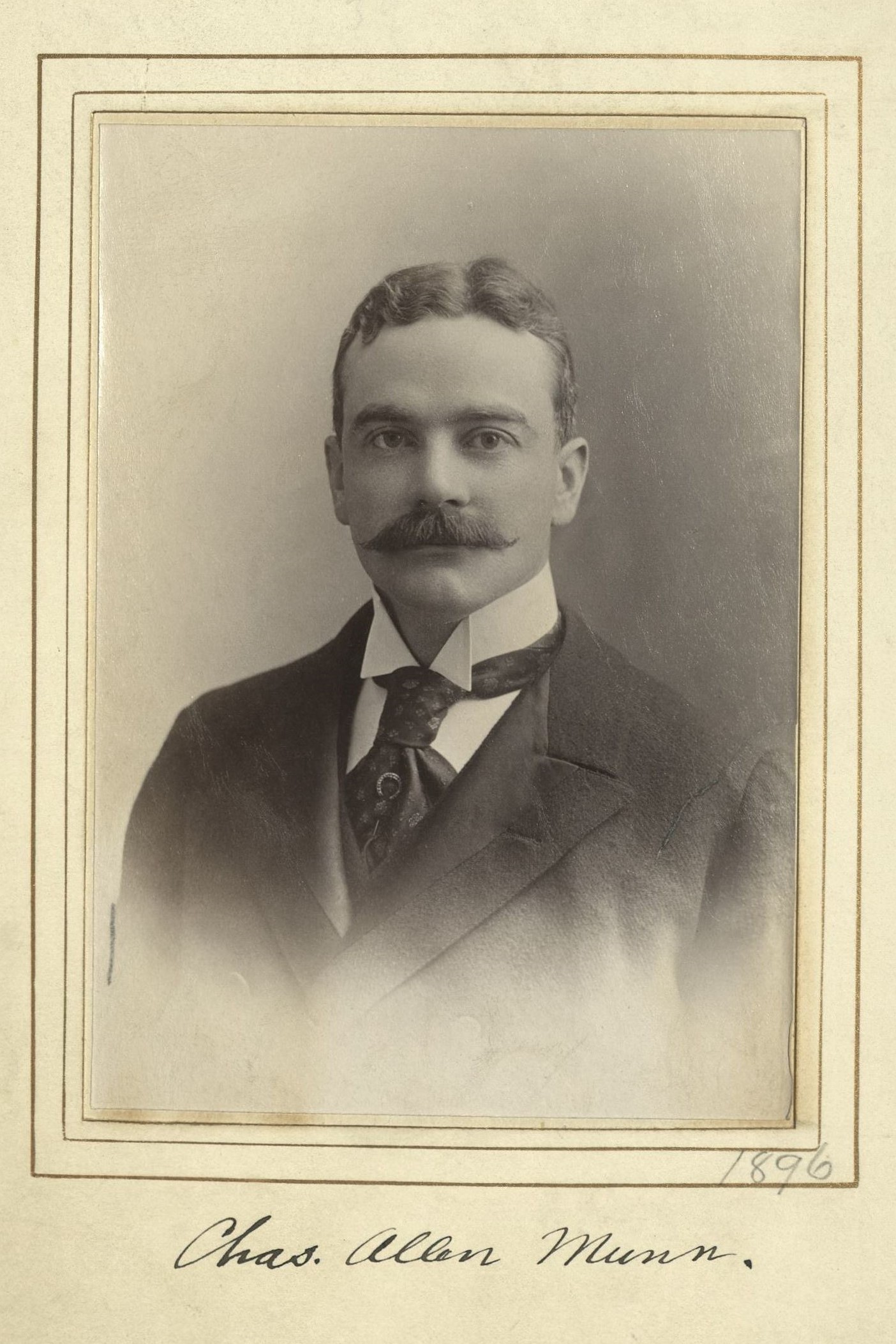

Charles A. MunnPublisherCenturion, 1896–1924

Charles A. MunnPublisherCenturion, 1896–1924 -

William M. SpackmanRailway Business/FinancialCenturion, 1896–1925

William M. SpackmanRailway Business/FinancialCenturion, 1896–1925 -

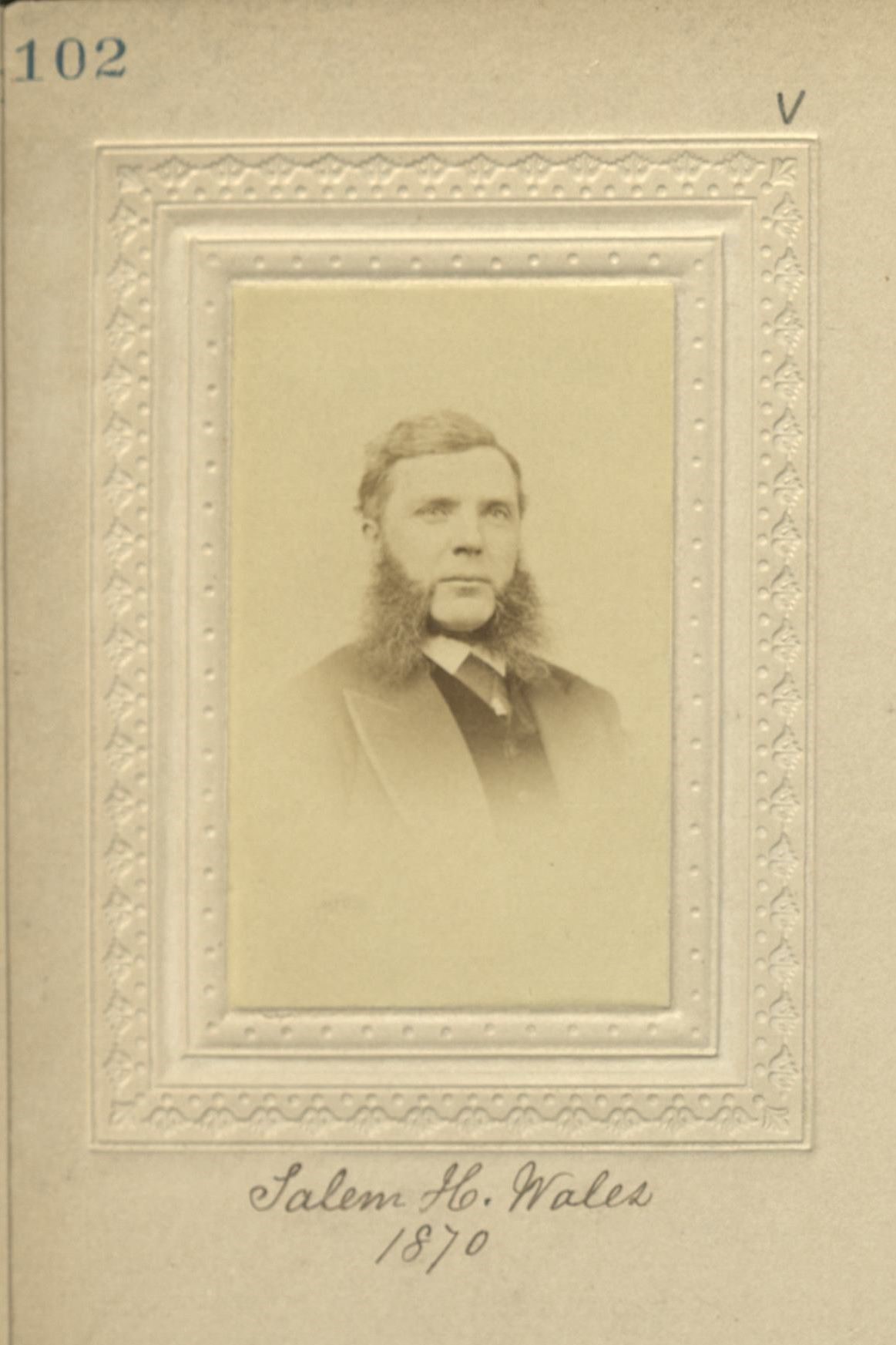

Salem H. WalesEditor, Scientific American/Public ServantCenturion, 1870–1902

Salem H. WalesEditor, Scientific American/Public ServantCenturion, 1870–1902