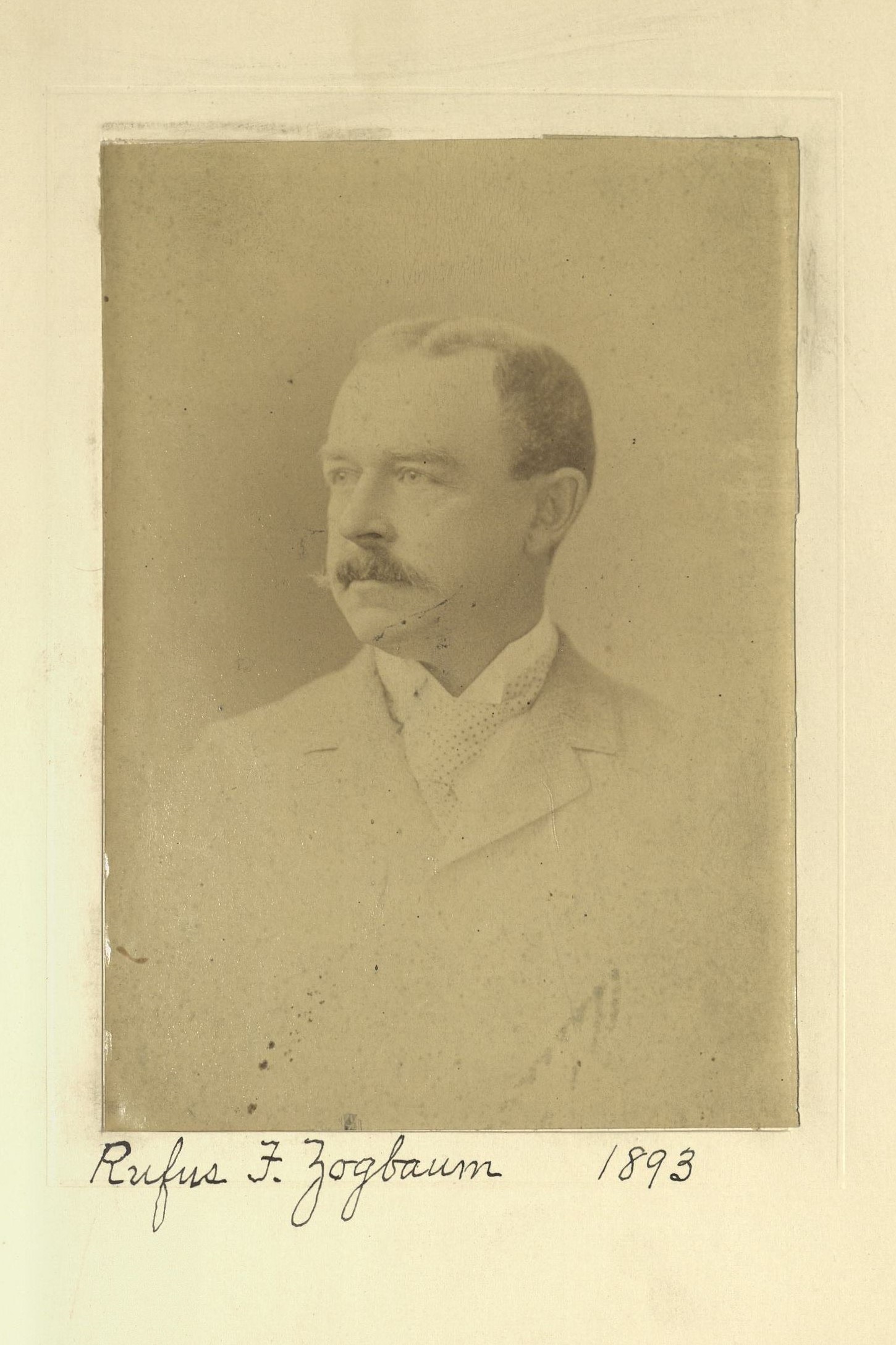

Artist

Centurion, 1893–1925

Born 28 August 1849 in Charleston, South Carolina

Died 22 October 1925 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Charles S. Reinhart and Francis Davis Millet

Elected 2 December 1893 at age forty-four

Archivist’s Note: Father of Harry St. Clair Zogbaum

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

One other very familiar figure at the Century’s dinner-table has left us in the twelvemonth. Most of his fellow-Centurions will remember Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum chiefly for his bluff and burly personality and his store of quaint anecdote; others will associate him with a curious career. He was distinctly of the army and navy, never in them. It was not at all difficult to imagine Zogbaum on the bridge, his weather-beaten face looking out from under the naval service-cap, and with the four bars on his sleeve, as he brought his cruiser into action. If in actual fact he only sketched the battle-ships and crew, the touch was singularly intimate, and the navy hailed him as its own. The Archibald Forbeses and Philip Gibbses who write for the press the story of the army at the front make up a distinctive group in the personnel of war. By their pencil, if not by their personalities, the men who drew the camps and battles of the Civil War for Harper’s Weekly and of the Russo-Turkish war for the Illustrated London News are associated with those campaigns in the public mind quite as intimately as the military staff. But Zogbaum was not of that company. Officers of the line, whose stiff professional tradition resented intrusion by the usual emissaries of the press, always had an outstretched hand for him. He knew the army better than an enlisted man could know it. Hopkinson Smith, half-enviously, wrote that Zogbaum was “familiar with everything about the service, from a buckle to an army blanket”; that “his delineation of army life and army equipment is as correct as an army manual.” The most delicate dedicatory compliment which Kipling could inscribe to Captain Bob Evans of the Iowa suggested that, while “Zogbaum does things with a pencil” and “I do things with a pen,” the principal contrast between the sea-dog and the landsmen was that “you sit aloft in a conning-tower, bossing a thousand men.” Kipling would not have put many illustrators into his picture.

The modern battle-ship, whose harsh outlines suggest to most people only regrets at the vanished romance of the navy, stirred Zogbaum’s imagination. His introduction to his volume of drawings of navy life remarks perfunctorily on the by-gone days of the frigate “with its tapering masts and towering sails,” but describes with admiration the “leviathans of steel and iron, more terrible in their capacity for destruction than the fabulous monsters of antiquity.” Whoever has seen his “Battle-ship in Action,” ploughing the sea directly towards the foreground of the picture, his “Night Evolutions” of cruisers manoeuvering in the moonlight, his “Evening Colors” with its suspended action on the deck but restless motion in the water, has had a glimpse of living things.

In spirit one of the ship’s company at sea, Zogbaum was in spirit a salt-water man on land. Some of us will remember his exasperation, after hearing Madam Butterfly at the Opera, for having wasted time at a performance in which an officer of the United States Navy was made to commit the solecism of wearing his uniform on shore leave. Members of Zogbaum’s family, after mentioning a visit to Newport, would explain that this did not mean the Newport of popular tradition, since Zogbaum spent his holiday on a bench in the dingy district by the wharfs, talking sea-lingo with the sailors.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1926 Century Association Yearbook