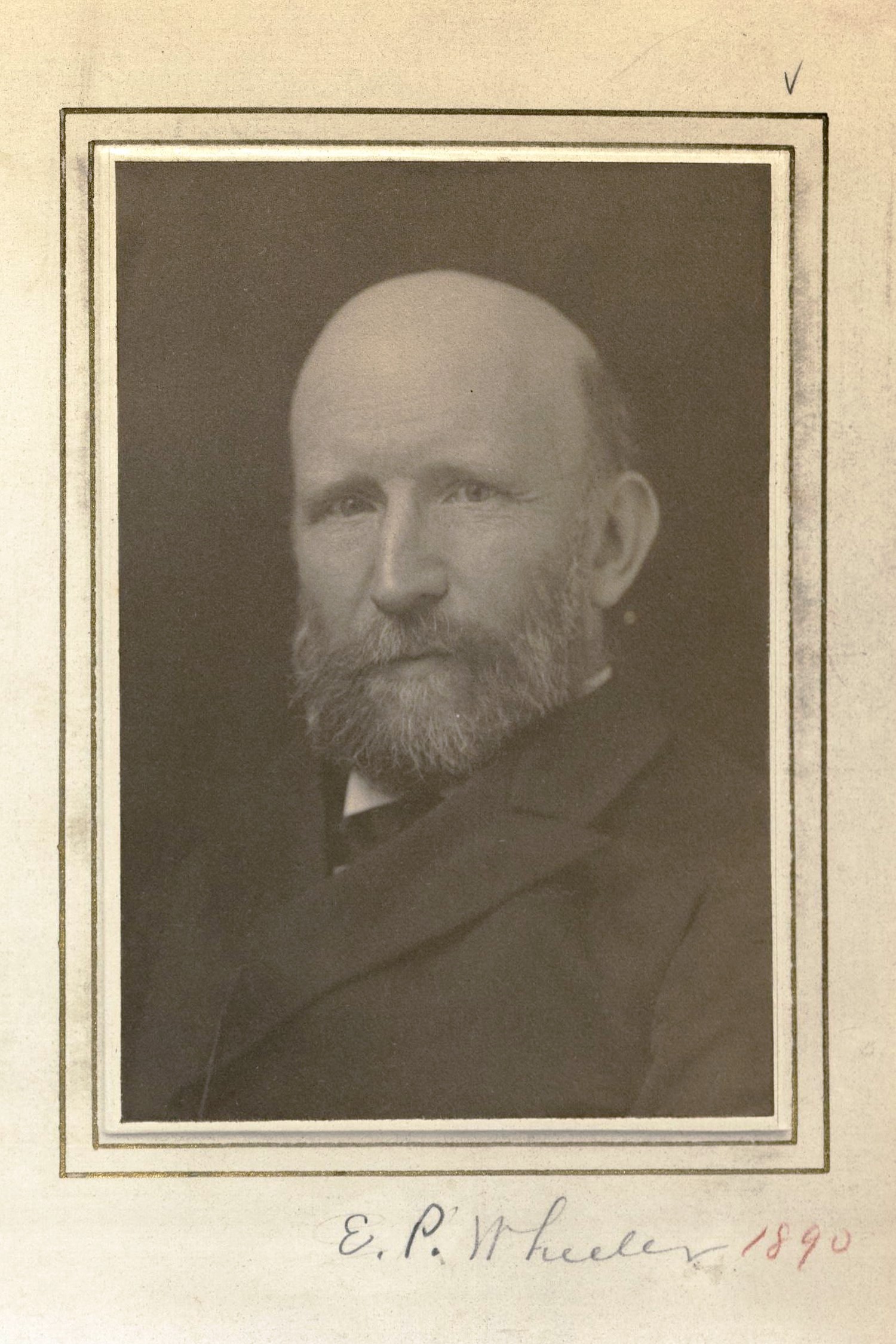

Lawyer/Civil Servant

Centurion, 1890–1925

Born 10 March 1840 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 8 February 1925 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Russell Sturgis and Henry A. Oakley

Elected 4 October 1890 at age fifty

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

Of some men, though not of many, it may be said that they are the embodiment, in career as in personality, of a past political era. The “Mugwump movement” is to the present generation almost as shadowy a tradition as was that of the Hunkers and Barnburners to this generation’s grandfathers. Everett Pepperell Wheeler never called himself a Mugwump. As a lifelong Democrat, indeed, he could hardly qualify under the usual political definition, which was a voter who had abandoned the Republican party of the eighties because the ideas and principles which attracted him were supported only by the Democratic platforms and candidates of the day. Nevertheless, there were few of the Mugwump characteristics which were not conspicuously Wheeler’s. His whole career embodied what the Mugwumps themselves called putting their own convictions of public welfare above party regularity, but what the party oracles of the day contemptuously described as the “holier-than-thou attitude.” Wheeler was thus described by the phrase-makers of his own party, long before the Mugwumps came upon the scene, and in his case, as in theirs, the irritation of party leaders was driven to white heat by his calm acceptance of the scornful description. Politically, they were not as holy as he was; he knew it, though he had left it for them to say. Scorn and resentment in the ranks of party regularity were a delight to the militant Mugwump, and so they were to Wheeler.

Having helped to found the Civil Service Reform Association in 1877, Wheeler was presently confronted with the angry comment, repeated with high approval in official Washington, that Civil Service reform was “the colossal fraud and humbug of the age.” It cheered him immensely; it was proof of the stubbornness with which party leaders hugged the spoils-system to themselves, and it meant a fight worth fighting. Nothing could so faithfully have reflected the old-time Mugwump twist of mind as Wheeler’s explanation of the appearance of 1500 members of the bar in the “Cleveland parade” up Broadway, just before the election of 1884. Regular party men declared, not without seeming plausibility, that this regiment of lawyers was made up of Democrats masquerading as independents; that the pretense of a spontaneous demonstration by the bar for the Democratic candidate was a piece of impudence; that it was merely expression of individual party feeling. But Wheeler answered the challenge with true Mugwump particularity. He wrote to the newspapers that the 1500 responsible lawyers who participated in the parade “did this in order publicly to advise our clients that we had studied the ‘Blaine letters,’ that we were convinced as lawyers that he had sold his official power and influence for railway bonds and that, if president, he would do the same thing again.” No reply could possibly have been more provoking, three days before election, than this calm and didactic version of the matter. Any Centurion who knew him in later days can picture Wheeler writing it.

Not as a political free-lance, but repeatedly as a party insubordinate, he fought his political battles relentlessly; never asking anything for himself and never knowing when he was beaten. “Tariff reform” was in Wheeler’s eye a formula for timorous minds; he preached free trade unreservedly, from the seventies onward. When he disapproved a public policy he always came into the open to oppose it, even if such action brought unpleasant notoriety. Not everybody, even if he held Wheeler’s opinion in the matter, would have cared to conduct as its president during a term of years, as Wheeler did, the activities of the Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. He stood for sound money through the successive phases of greenbackism and free silver coinage; nobody ever had reason to doubt where to find him in any revival of the old delusion with a new face. His manner of fighting was shown by his participation in organizing the Bar Association in 1869, when the Tweed Ring ruled New York, and by his share the next year in starting, through that organization, impeachment proceedings against the corrupt judges whom the Ring controlled. Charles O’Conor said at Albany to Wheeler and his colleagues, “You must kill them or they will kill you.” This must have delighted Wheeler.

Yet, with all this militant reforming instinct, Wheeler was never the harsh and sour Puritan man-at-arms. His judgment of statesmen of the opposing party was surprisingly humane; McKinley, he remarked, “developed more steadily than any other public man that I ever knew.” But so was his appraisal even of the political rogues whom he was hunting down. When the conflict between Cleveland and Tammany was at its height with Wheeler on the side of Cleveland, and some one remarked on the respectable appearance of the Wigwam’s delegation at Chicago, Wheeler volunteered the explanation that “there are a great many very good citizens in Tammany.” William M. Tweed himself “was in many respects a man of broad intelligence.” Here, after all, is something of the political philosopher as well as the political reformer.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1926 Century Association Yearbook