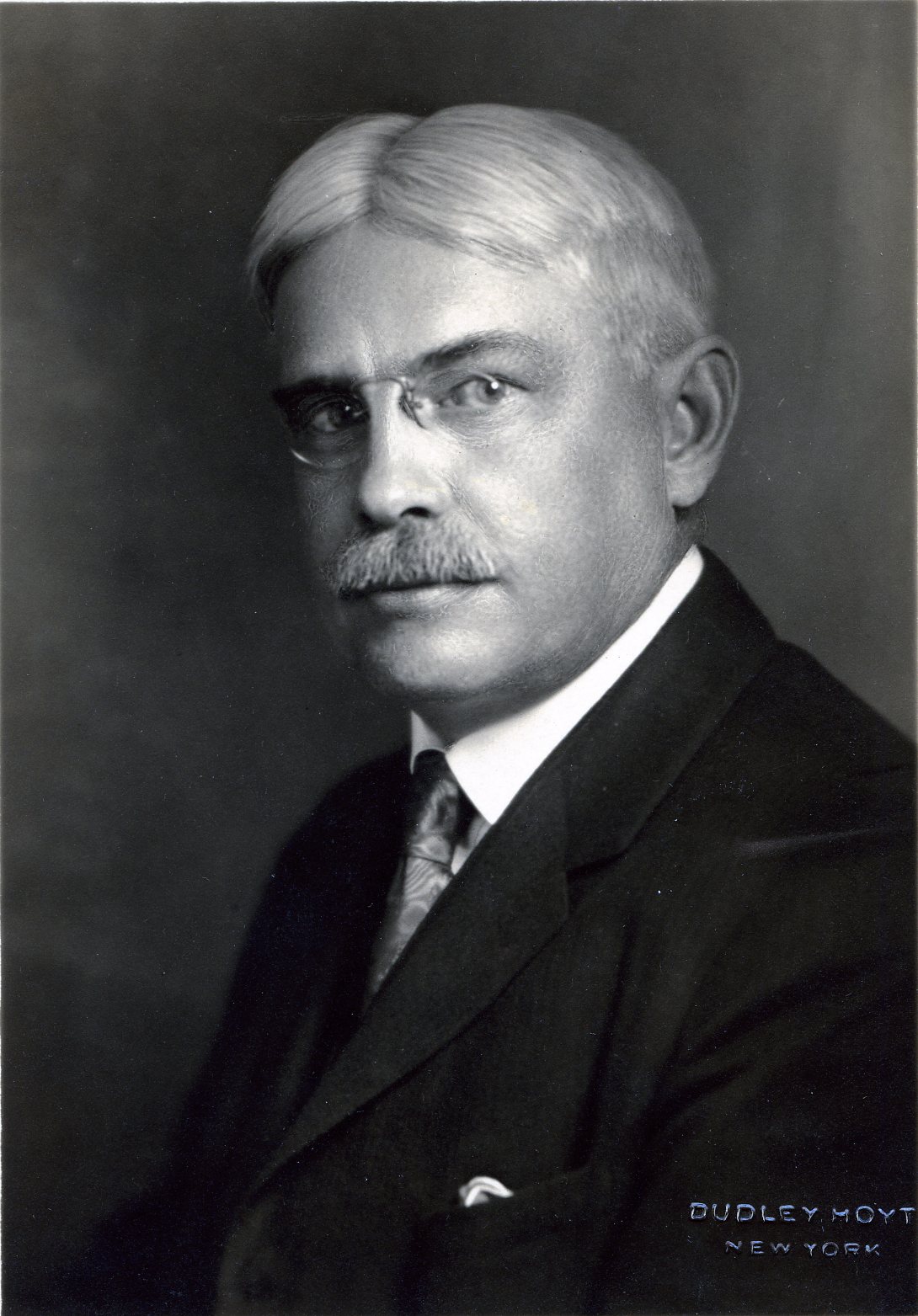

Professor of English Literature

Centurion, 1909–1933

Born 26 December 1871 in Houlton, Maine

Died 17 April 1933 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Forestdale Cemetery, Holyoke, Massachusetts

Proposed by Brander Matthews and Stephen H. Olin

Elected 6 November 1909 at age thirty-seven

Archivist’s Note: Brother of Edward L. Thorndike and Lynn Thorndike

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

It was the special preoccupation of Ashley Horace Thorndike to study Shakespeare the playwright in the light of Shakespeare the playhouse manager. To the long list of earlier Shakespearian commentators, the fact that the subject of their study should have directed the business of his theatre so efficiently as to enable him to retire with a competency from that precarious occupation, was admitted to be a puzzle; but they did no more than guess about it. Thorndike, while giving place to none of them in appreciation of the dramatist, approached the question as a problem in the history of a Seventeenth-century Frohman or Belasco. After all, Shakespeare the manager had to draw audiences to the Globe. His business was to ensure a “record run” if possible, and the taste or whim of Elizabethan play-goers shifted as frequently and as disconcertingly as did those of Sothern’s audiences. Thorndike examined all accessible records of the contemporary theatre, traced them along with the recorded changes in the period’s public mood, compared them with the corresponding changes in the themes of Shakespeare’s plays, and convinced the critics.

Why did “As You Like It” follow so quickly after Shakespeare’s plays of English history? Because popular taste for stage reproduction of past British politics had waned, and because the fickle public fancy was being caught by pastoral comedy and Robin-Hood impersonation. Why did “Hamlet’’ and the tragedies capture audiences which had been content with Rosalind, Falstaff and Sir Toby? Because other producers were drawing better houses with plays of conspiracy and revenge. Even “Measure for Measure,” a Shakespearian play quite unlike those which preceded it or followed, was, in Thorndike’s view, an experiment suggested by the not unsuccessful effort of competing managers to bring the sex-drama into vogue.

Above all, what caused Shakespeare abruptly to abandon in his closing years the highest themes of tragedy, and to enter the field of purely romantic drama? Thorndike gives evidence that public favor had been drifting from “Othello” or “King Lear” to the idyllic plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, and concludes that this was why the experienced author-manager forthwith deserted tragedy to regain the field against these younger innovators. “Cymbeline,” “Winter’s Tale” and “Tempest,” achieved the task. This extremely interesting venture into original literary criticism does not solve the whole of the Shakespeare mystery, but it throws light on a neglected side of it.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1934 Century Association Yearbook