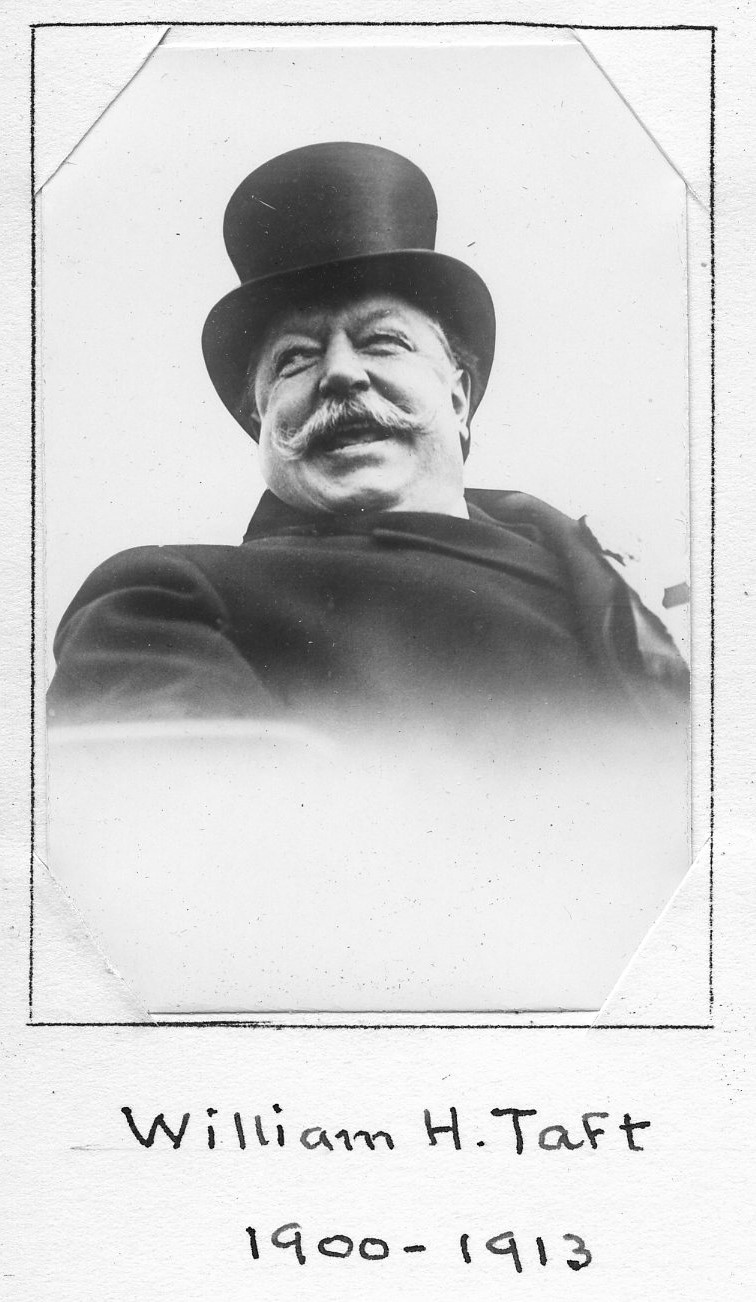

Professor, Yale University/U.S. President/Chief Justice of the United States

Centurion, 1913–1930

Born 15 September 1857 in Cincinnati, Ohio

Died 8 March 1930 in Washington, District of Columbia

Buried Arlington National Cemetery , Arlington, Virginia

, Arlington, Virginia

Proposed by John C. Spooner and Arthur T. Hadley

Elected 1 November 1913 at age fifty-six

Archivist’s Note: Brother of Henry W. Taft

Century Memorials

William Howard Taft was one of the very numerous individual links between the Century and the national government at Washington. Joining the Club only in 1913, some months after his presidential term expired, he was not in the series of Century members who occupied the White House during twenty out of the thirty-seven past years. But he was the first Centurion to fill the place of Chief Justice in the United States Supreme Court, and it is interesting to remember, not only that he found two other Century members on that bench when he was named for it in 1921, but that his own successor in the chief justiceship is still another Centurion.

Justice Taft was only a casual visitor at the Century; where, however, he always found himself the centre of a friendly circle at the Club-house and where the atmosphere of cheerfulness and good humor that radiated from his portly presence invariably brightened the occasion. It has often been pointed out that Mr. Taft’s political career was unusual for the widely diversified range of responsibilities which almost half a century of public life imposed upon him. But in two other respects his career was wholly exceptional in our history. He was the only candidate of a partly in power who was ever elected president of the United States in immediate sequence to a great financial panic. He was the only president who was destined, after relinquishing that office, to hold another place of equal public distinction. There have been occupants of the White House—John Quincy Adams and Andrew Johnson are examples—who returned in a modest way to public life, even after their one-term service in the presidency had ended with popular rejection of them. But there is no other instance of a president who had been defeated for re-election, whose presidential term had been widely described as political failure, being subsequently raised, with unanimous popular approval, to another of the greatest offices in our government.

That this should have been possible with Mr. Taft was partly because of the people’s belief in his high individual qualities and absolute integrity; partly because of their feeling that he would have been more fortunate if, instead of becoming heir-apparent to the Presidency, he had accepted Roosevelt’s earlier proffer to him of a Supreme Court justiceship. But also, and by no means least, it was because of the engagingly human aspects of his personality, exhibited perhaps as much in his official mistakes as in his official achievement.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1931 Century Association Yearbook

Taft was born in Cincinnati into the powerful Taft family, the son of Alphonso Taft who served as Secretary of War under President Ulysses S. Grant. Taft graduated from Yale in 1878, and from Cincinnati Law School in 1880. He was appointed a judge to the Ohio Superior Court in 1887, and then to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in 1891.

In 1900, President William McKinley appointed Taft Governor-General of the Philippines, which had been ceded to the U.S. by Spain. As Governor-General, the rotund Taft once sent a telegram to Washington that read, “Went on a horse ride today; feeling good.” Secretary of War Elihu Root replied, “How’s the horse?” In 1904, Roosevelt appointed Taft to succeed Root.

After serving for nearly two full terms, Roosevelt declined to run in the election of 1908 and supported Taft, who won an easy victory over William Jennings Bryan. In his only term, he emphasized trust-busting as a main issue, supported by his Attorney General George W. Wickersham. He strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission, improved the performance of the postal service, and helped the passage of the Sixteenth Amendment. In 1910, Taft, an ardent baseball fan, inaugurated a presidential tradition by throwing out the first ball at the Washington Senators opener. (His half-brother Charles Phelps Taft later purchased the Chicago Cubs.)

Taft made six appointments to the Supreme Court including Edward Douglas White and Charles Evans Hughes. With these two Taft essentially appointed both his predecessor and successor Chief Justices, respectively. White was named Chief Justice in 1910. Hughes later resigned to run as the Republican Party’s presidential candidate in the 1916 election, which he would lose. President Herbert Hoover nominated Hughes to the Court as Chief Justice following Taft’s retirement.

Near the end of Taft’s first term, Roosevelt turned on his former protégé in one of the most dramatic political feuds of the 20th century. But Taft outmaneuvered the popular Roosevelt and seized control of the GOP. Taft had the backing of many former Roosevelt boosters, including Elihu Root, Henry L. Stimson, and Roosevelt’s own son-in-law, Nicholas Longworth. Out of the 14 Republican primaries held, Roosevelt won nine, and Taft won just three. Robert La Follette won the other two. Still, Taft won the nomination at the convention.

Roosevelt was forced to create the Progressive Party (or “Bull Moose”) ticket, splitting the Republican vote in the 1912 race, allowing Woodrow Wilson’s election. Taft won just the eight electoral votes of Utah and Vermont, making it the single worst defeat in history for an incumbent president seeking reelection.

Taft served as a law professor at Yale until President Harding made him Chief Justice of the United States, a position he held until just before his death in 1930. To Taft, the appointment was his greatest honor; he wrote, “I don’t remember that I was ever President.”

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)