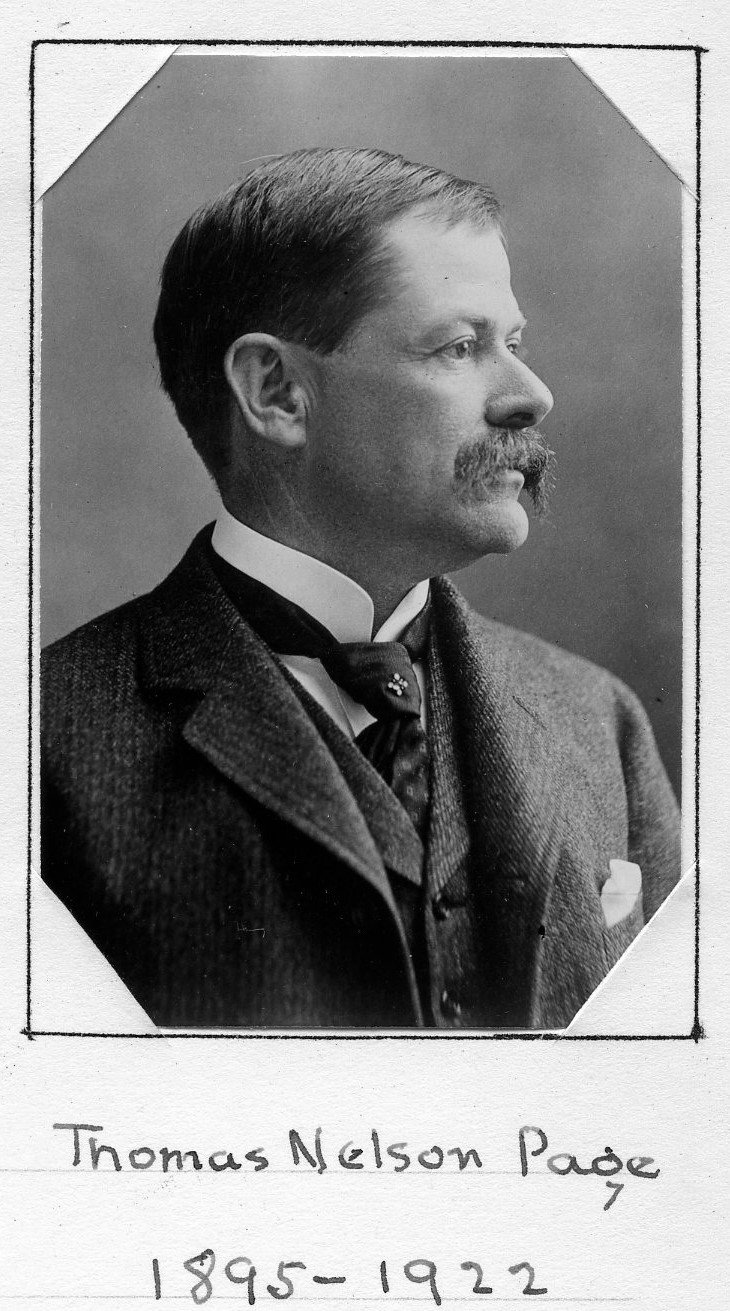

Author/Diplomat

Centurion, 1895–1922

Born 23 April 1853 in Beaverdam, Virginia

Died 1 November 1922 in Beaverdam, Virginia

Buried Rock Creek Cemetery , Washington, District of Columbia

, Washington, District of Columbia

Proposed by F. Hopkinson Smith, Edmund C. Stedman, and Francis Lynde Stetson

Elected 5 October 1895 at age forty-two

Century Memorial

Those numerous people who are alternately scandalized and plunged in despair because the lately belligerent European states have not yet succeeded, four years after the war, in living together in cordial amity and high prosperity, do not seem to be acquainted with the successive chapters of social and economic chaos, of reconstruction and at last, long afterwards, of reconciliation, through which our own South had to pass after the Civil War. The third of those chapters was not actually completed until twenty-five years after Lee’s surrender. Its completion was hastened by many occurrences of the later period; such, for instance, as the famous speech at the New England Society dinner of 1886 in which Henry W. Grady, picturing the new South and its new view of the future, put into words the friendly mutual feelings which were displacing the animosities of war. But for influence on the mind and imagination, nothing accomplished more in bringing about the spirit of reconciliation than the half-dozen short stories, with their tender reminiscence of the South of reconstruction days, which Thomas Nelson Page began to write in 1887 and which touched the heart of the Northern reader as no other appeal could have done.

For that achievement Page was fitted, not only by his graceful style and sure literary touch but by his personal associations. Only eight years old when Sumter was fired upon, he never saw actual service with the Confederate regiments. Probably his memory of the political hatreds of 1861 was as dim as the recollection which the German and Austrian boys of college age must nowadays have of the controversies of 1914. But he was old enough to remember, as a childhood memory would revive such pictures, the patriarchal Virginia society of pre-war days; to recall personal incidents before and after the battles—which indeed were fought within hearing of his father’s house—and to have a very personal share in the poverty and hard times that followed the war.

Here was the background for his stories. Had he grown up in South Carolina or Mississippi, Page might have been unable afterward to shake off the bitterness of sentiment with which those communities entered the conflict; but being a Virginian, it was possible for him to remember it with kindlier feelings, even though his own state had been the principal theatre of war. That he never looked at the Union with the eyes of an “unreconstructed” Southerner, that the romance of the war appealed to him far more strongly than its political or economic issues, are considerations which largely explain the particular place he holds in American literature and American history.

Scores of old friends, in and out of the Century Club, will recall Page’s genial temperament, hospitality, charm of manner and conversation. Probably no contemporary author had a wider circle of personal acquaintance north and south, in this country and in Europe, and his six years as Ambassador to Italy broadened his associations as they broadened his outlook on life and history. He had meant to publish his personal recollections of the Great European War, and they would have been full of interest. Yet it would have been even more interesting if he could have lived to observe with his sympathetic eye and describe with his sympathetic pen the plain people of Continental Europe in reconstruction.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1923 Century Association Yearbook