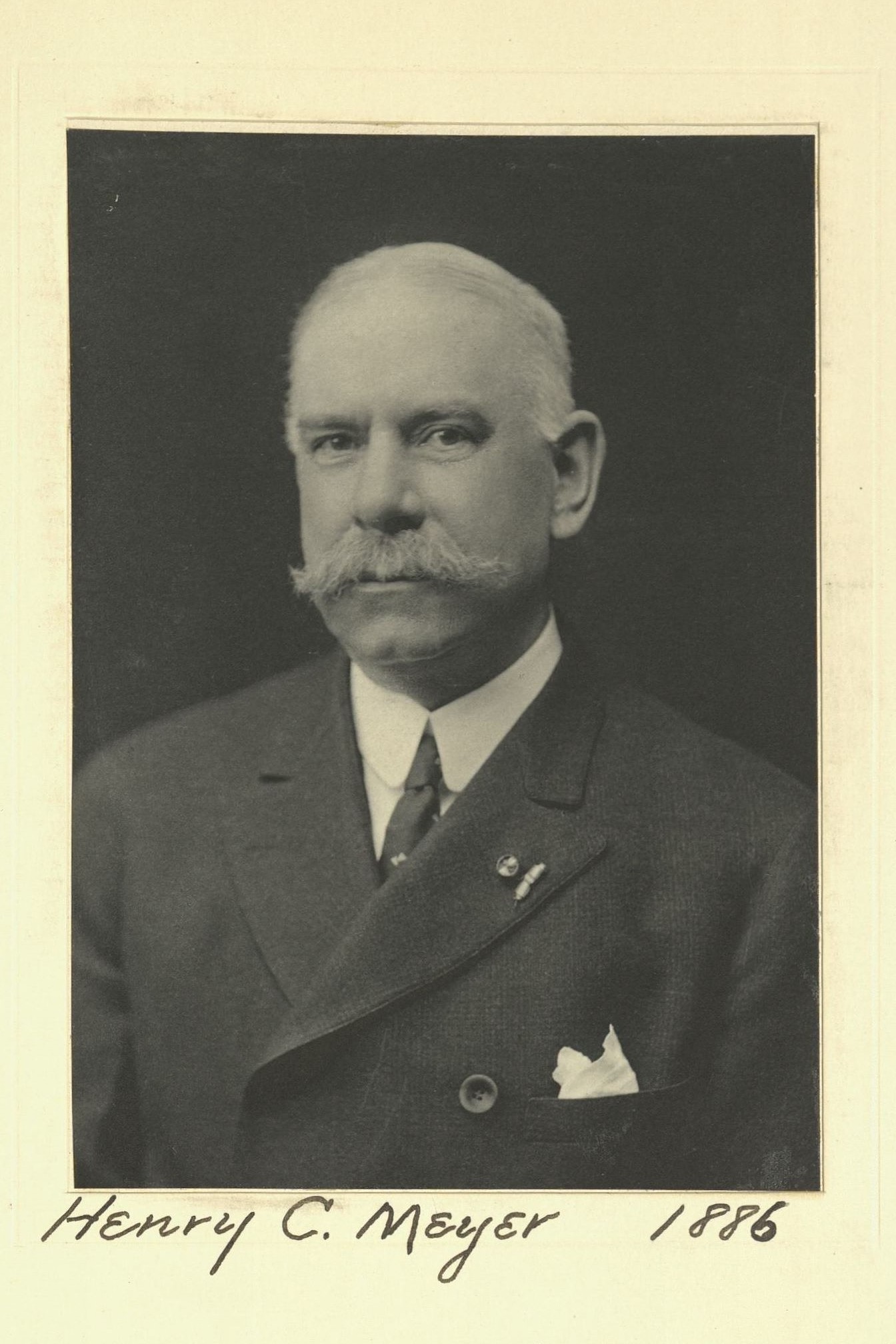

Editor

Centurion, 1886–1935

Born 14 April 1844 in Hamburg, Germany

Died 27 March 1935 in Montclair, New Jersey

Buried Rosedale Cemetery , Orange, New Jersey

, Orange, New Jersey

Proposed by Richard Morris Hunt and Richard T. Auchmuty

Elected 5 June 1886 at age forty-two

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

Henry Coddington Meyer was the last of our living membership who had seen active service in the Civil War. When Fort Sumter fell, the seventeen-year-old boy proposed his own immediate enlistment. His father having refused permission and having persisted in refusal, Meyer had himself sworn in for three years’ service without parental consent. Meyer’s father, as the Major afterward recalled, was exceedingly angry and his mother much distressed. A friend of the family amiably remarked, “It is too bad; that boy has gone to the devil.” With this not wholly auspicious household blessing, the boy began a gallant cavalry career. He fought at Antietam, at Fredericksburg, at Gettysburg and in the Wilderness; he was promoted successively to the posts of second lieutenant and captain, finally being brevetted major.

Even in his old-age reminiscence of war-time service, the Major had the happy faculty of describing personal incidents, often unimportant in themselves but throwing their light upon the period. On occasion he would recall to his later-day intimates how a fellow-soldier, bringing to the rest the news of McClellan’s removal from command, began to cry on making the announcement; how, serving on picket duty the night before the disastrous Union defeat at Fredericksburg, he could hear the enemy’s artillery moving to position and men making speeches to the troops; how Grant, riding along a road on which weary soldiers were asleep, forbade the officers to rouse them, changing his course and that of his staff to the adjacent field. Sometimes the Major could be persuaded to tell of his own single combat on horseback with an enemy cavalryman, under fire of Confederate foot-soldiers who blocked his way—a dilemma from which Meyer escaped only by jumping his horse over fence and ditch. Twice he was dangerously wounded; he carried in his leg for the rest of his life a bullet which in 1935, when the wind was in the East, gave him unpleasant reminder of 1864.

The war over, our Major went into the business of manufacturing household plumbing supplies. He and his family were attacked with virulent diphtheria. Examination of the premises, the Major wrote, “showed that our bedrooms were without protection from sewer-gas and that, though my business was manufacturing supplies for plumbing, gas and steam work, I had never taken the trouble to examine the drainage of our own house.” To impress his discoveries on other people, Meyer successfully established the monthly Sanitary Engineer, of which, under that and its later title of the Engineering Record, he was for twenty-five years the active and useful editor. Never being in the habit of doing things by halves, Meyer’s program went beyond mere editorial success. Once convinced that a large-scale sanitary reform was necessary, he personally undertook to bring the State legislature into line with his ideas. Any Centurion who remembers the Major’s pertinacity in conversation, his uncompromising defense of principles he believed in, his readiness to explain at any length the underlying facts, can imagine how he wore down the opposition of an Albany committee which insisted that the law as it stood was good enough. All but single-handed, he compelled the legislature to give the Health Department plenary power over plumbing and drainage in the city’s houses. He forced it to abolish the “deadly railway car stove,” and did so, not alone by citing the record of conflagrations after railway wrecks but through demonstrating convincingly, in his testimony at Albany, that the warming of cars by steam from the locomotive was entirely feasible. These were but two of the numerous reform plans of which, during the Eighties, the Major was the resolute protagonist. Even when he had withdrawn entirely from active work, he was fond of visiting Washington during session time and attending Congressional committee inquiries. The Century of today will picture him most clearly exchanging ideas and reminiscence with Major Putnam, Dr. Hills, John Tatlock, James Cromwell, and the rest of the Graham Library group of half a dozen years ago.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1936 Century Association Yearbook