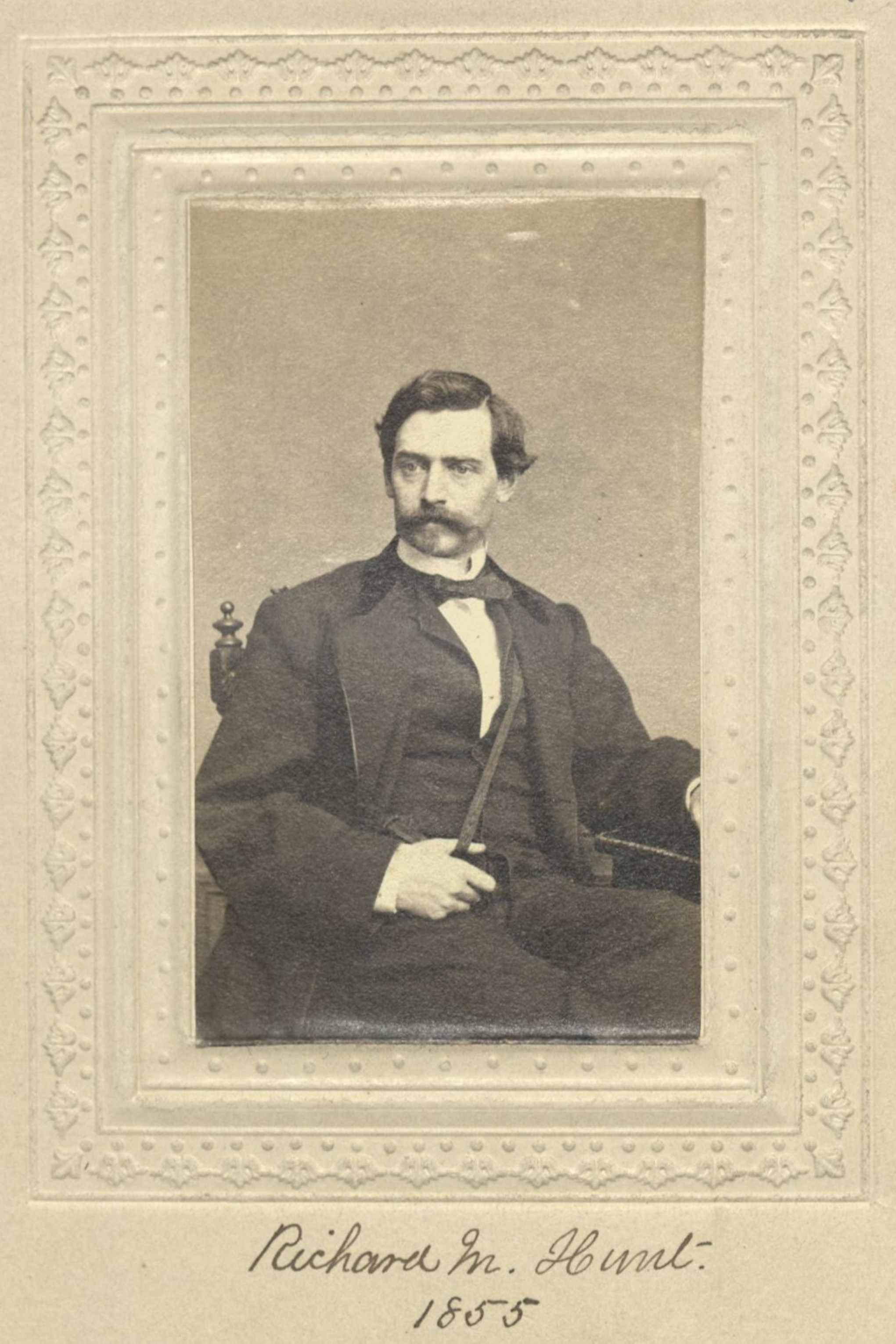

Architect

Centurion, 1855–1895

Born 31 October 1827 in Brattleboro, Vermont

Died 31 July 1895 in Newport, Rhode Island

Buried Island Cemetery , Newport, Rhode Island

, Newport, Rhode Island

Proposed by Henry D. Sedgwick

Elected 1 December 1855 at age twenty-eight

Archivist’s Note: Brother of Leavitt Hunt; father of Richard H. Hunt; grandfather of Richard C. Hunt

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Supporter of:

Century Memorials

It is unnecessary to suggest to any member of The Century the loss it has sustained by the death of Richard M. Hunt. He was so conspicuous a figure in our membership, and conferred such a distinction upon it, that, even to those not honored with his acquaintance, his death brings a sense of personal loss, which, to his intimate friends here, is irreparable.

Descended from a family of the best New England stock—famous for the artists it has produced—gifted by nature and trained under the most distinguished masters of his art in France, giving in his youth evidence of his power by his work on the pavilions of the Tuileries, he became by universal recognition the leading architect of America, and as such received honors from abroad, rarely conferred, and the highest appreciation at home.

In the work of his profession, which leaves its impress upon a country for all time, he was its foremost and most inspiring figure. Many beautiful structures attest his taste, his learning, and his intensely artistic spirit; but those who knew his career and its surroundings more intimately will best remember him by the ambitions that he excited in others, by the wonderful vitality that he imparted to the whole art movement about him, and by his absolutely unselfish devotion to the best interests of the profession that he adorned.

The American Institute of Architects, of which he was the founder and for a long time President, is not the least of his contributions to its service. He was broad minded, manly and generous in his associations with his professional brethren, ever ready with advice and assistance to those who sought it, untainted by professional jealousy, and of such conspicuous fairness and ability that his decision was sought and accepted as final in the strenuous competition for great architectural work.

He was one of the old-time members here, and bore about him the traditions of our golden age. He was a man of genius and of heart, and in those qualities of both, whereby the great army of his friends knew him, he was one of the unique and charming personalities of his time. Peculiarly happy in his domestic life, and occupying an enviable social position, association with him was as refreshing as the breath of the northwest wind. Always the centre of an admiring group—cheery, picturesque, eager and eloquent, pouring out a torrent of language, accompanied by exclamation and gesticulation, when words failed, he lifted his listeners from their feet with his enthusiasm, and they walked with him above the earth.

The country owes him a large debt of gratitude for his contribution to its art, in any branch of which he would have excelled. But he has left no monuments to denote his strength and power to posterity, equal to the growth which it has made during the last quarter of a century, which is inseparably identified with his own career.

Farewell, old friend! Life has lost a large share of its sunshine now that you are gone. Lofty aims and great accomplishments for you are ended, and the world is poorer for your going.

Henry E. Howland

1896 Century Association Yearbook

Hunt was a preeminent figure in the history of American architecture. According to New York Times critic Paul Goldberger, he was “American architecture’s first, and in many ways its greatest, statesman.” Hunt sculpted the face of New York City, including designs for the facade and Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and many Fifth Avenue mansions lost to the wrecking ball. He founded both the American Institute of Architects and the Municipal Art Society.

Hunt was born in Vermont and, following the early death of his father, his mother took the family to Europe, where they remained for more than a decade. The aspiring architect Hunt became the first American to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He later supervised work on the Louvre Museum, which was being renovated for Napoleon III, and he designed the Pavillon de la Bibliothèque.

After his return to America in 1855, Hunt founded the first American architectural school at his 10th Street studio building. One of his first students, William Robert Ware, went on to found the first two university programs in architecture: MIT in 1866, and Columbia in 1881.

Hunt’s greatest influence was his insistence that architects be treated, and paid, as legitimate and respected professionals equivalent to doctors and lawyers. He sued one of his early clients for non-payment of his five percent fee, which established an important legal precedent. He brought the first apartment building to Manhattan, and set a new grand style of houses for the social elite and millionaires of the Gilded Age.

After Hunt died in 1895, the Municipal Art Society asked sculptor Daniel Chester French and architect Bruce Price to design a memorial for him, which is installed in the wall of Central Park across from today’s Frick Museum. Following Hunt’s death, his son Richard Howland Hunt took over his practice.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)