Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

Henry van Dyke

Clergyman/Author

Centurion, 1888–1933

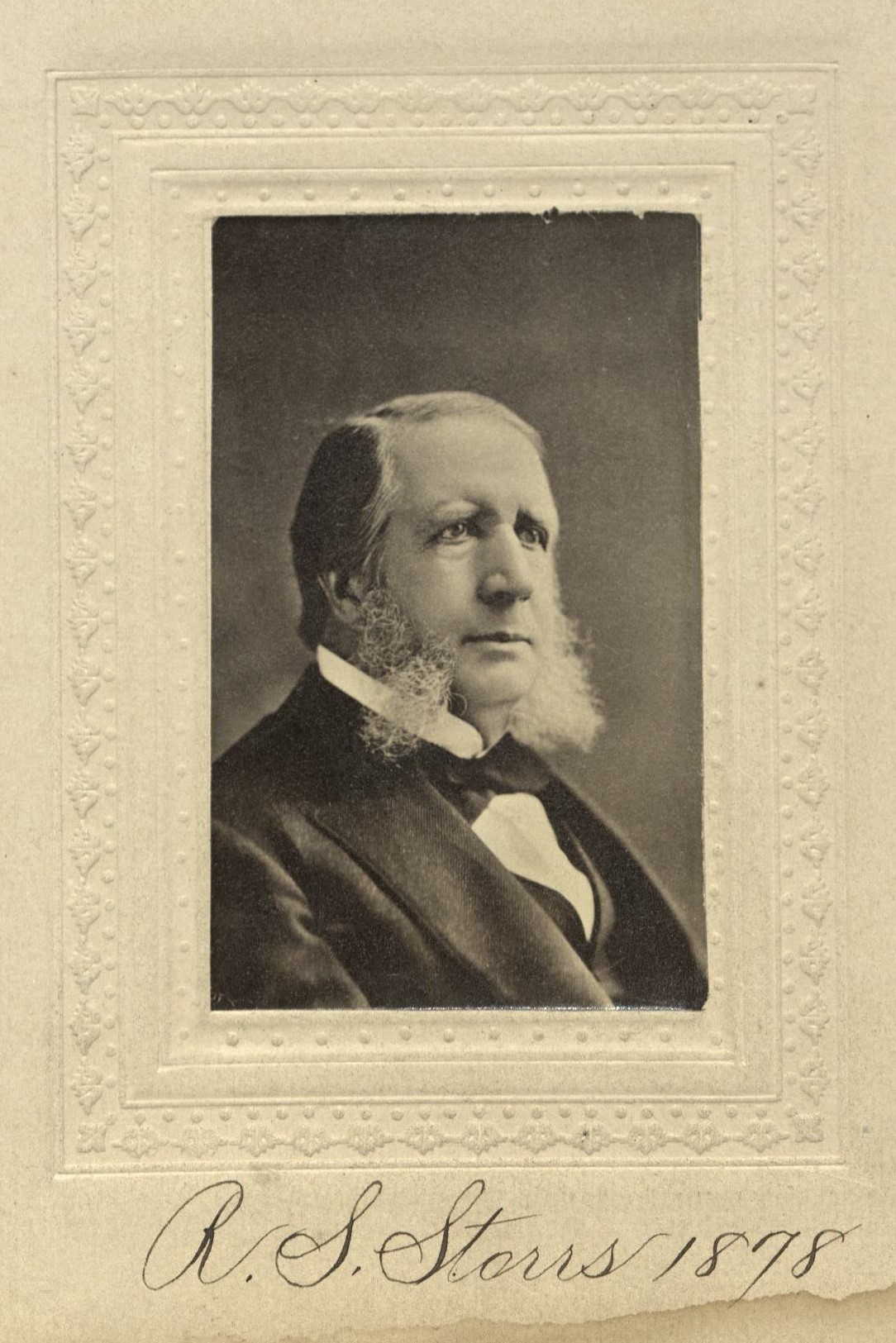

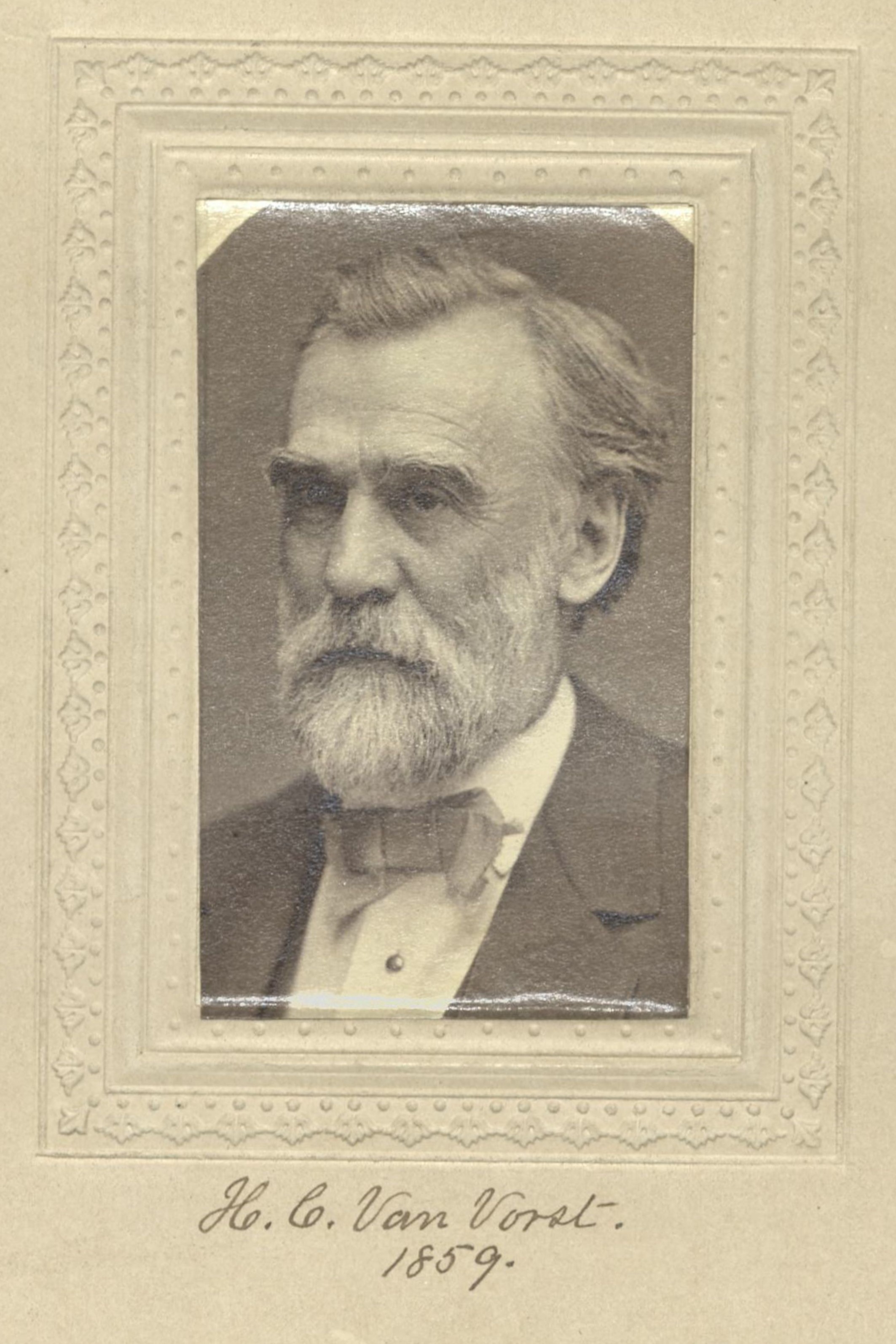

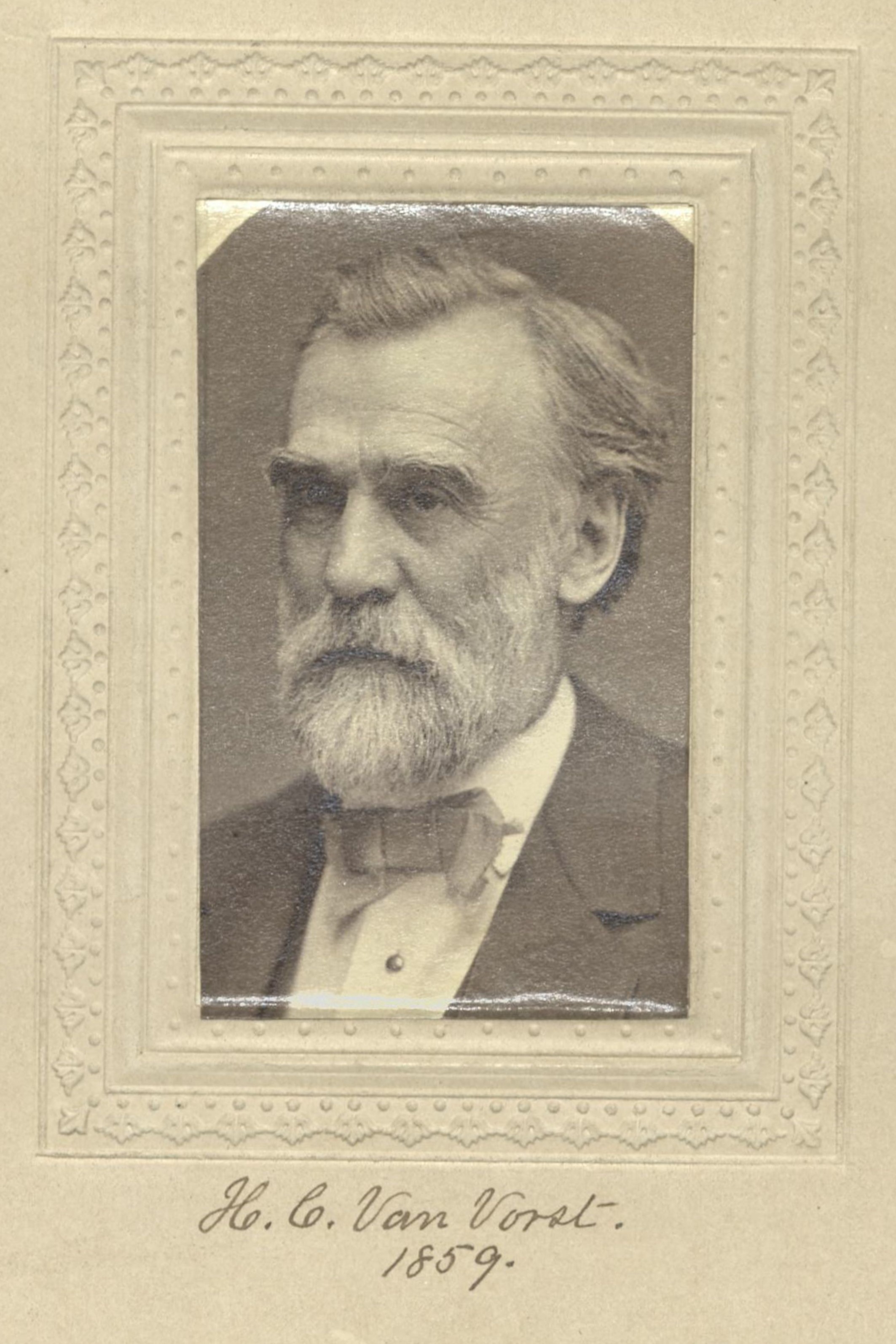

Hooper C. Van Vorst and Richard S. Storrs

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Princeton, New Jersey

Age thirty-five

Princeton, New Jersey

Archivist’s Notes

Brother of Paul van Dyke

Century Memorial

Centurions whose place at the dinner-table happened to be next Henry Van Dyke, and who listened to his thoughtful remarks on men and things, did not always know of the slumbering fire in their quiet fellow-clubman’s mind. As pulpit orator and teacher of English literature, Van Dyke had gained wide esteem; his culture, his imagination and the clearness of his judgment ensured it. His poetry was always graceful, sometimes inspiring. Isaak Walton would have liked to fish with him and exchange those ideas on the philosophy of life that complete anglers are expected to possess. But once away from church or lecture room or woods and streams, Van Dyke approached the questions of the day without conventional restraint. In the matter of religious creed, his contribution to popular controversy was a declaration that he himself was not a “Fundamentalist” and had been unable to discover what a “Modernist” was. The Eighteenth Amendment he discussed, not very patiently, as a moral and political absurdity. Calvinist ancestry did not interfere with his characterization of the “Anti-Catholic drive” in the campaign of 1928 as unscrupulous and base, a deliberate revival of religious intolerance for political advantage. Of the “new-school” fiction and drama of the early post-war period, he remarked contemptuously that it was as crude from the literary viewpoint as it was coarse from the viewpoint of good taste. When the Swedish Academy in 1930 voted the Nobel prize to Sinclair Lewis, Van Dyke described the award as mortifying to America, and suggested that the Academy must be badly versed in English.

It might be imagined that an independent thinker with this capacity for unsparing comment would have had his say at once on Germany’s conduct in the crisis of 1914. But Van Dyke’s situation was peculiar. In 1913 President Wilson sent him to represent the American government in the country of his ancestors. Accepting the mission to Holland as a charge for promotion of world peace, he presently found himself, through force of unexpected circumstances, in a distinctly warlike mood; yet he could not, at that neutral court, very well declare his personal judgment on the merits of the conflict, the duty of the United States, or the behavior of German armies. For a moment it seemed possible that the whirlwind of events would bring the German invaders into Holland, imposing on Van Dyke the task that befell Brand Whitlock in Belgium. Like Whitlock, he could then have spoken out concerning the exploits which present-day apologists describe as a display of natural irritation on the part of friendly visiting troops, maltreated by the Belgians. As it was, Van Dyke condemned himself to silence. It is fair to say, however, that when in 1917 he relinquished his diplomatic post and came back to America, he made up valiantly for the lost time of the four preceding years. This incisiveness of public speech was the quality of a poet and essayist whose writings breathe the spirit of gentle kindliness, of love for nature and for man in contact with her. But that is the paradox of humanity.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1934 Century Association Yearbook

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

Wilton Merle-SmithClergymanCenturion, 1902–1923

Wilton Merle-SmithClergymanCenturion, 1902–1923 -

William R. RichardsClergymanCenturion, 1903–1910

William R. RichardsClergymanCenturion, 1903–1910 -

Dean SageLumber/Book CollectorCenturion, 1899–1902

Dean SageLumber/Book CollectorCenturion, 1899–1902 -

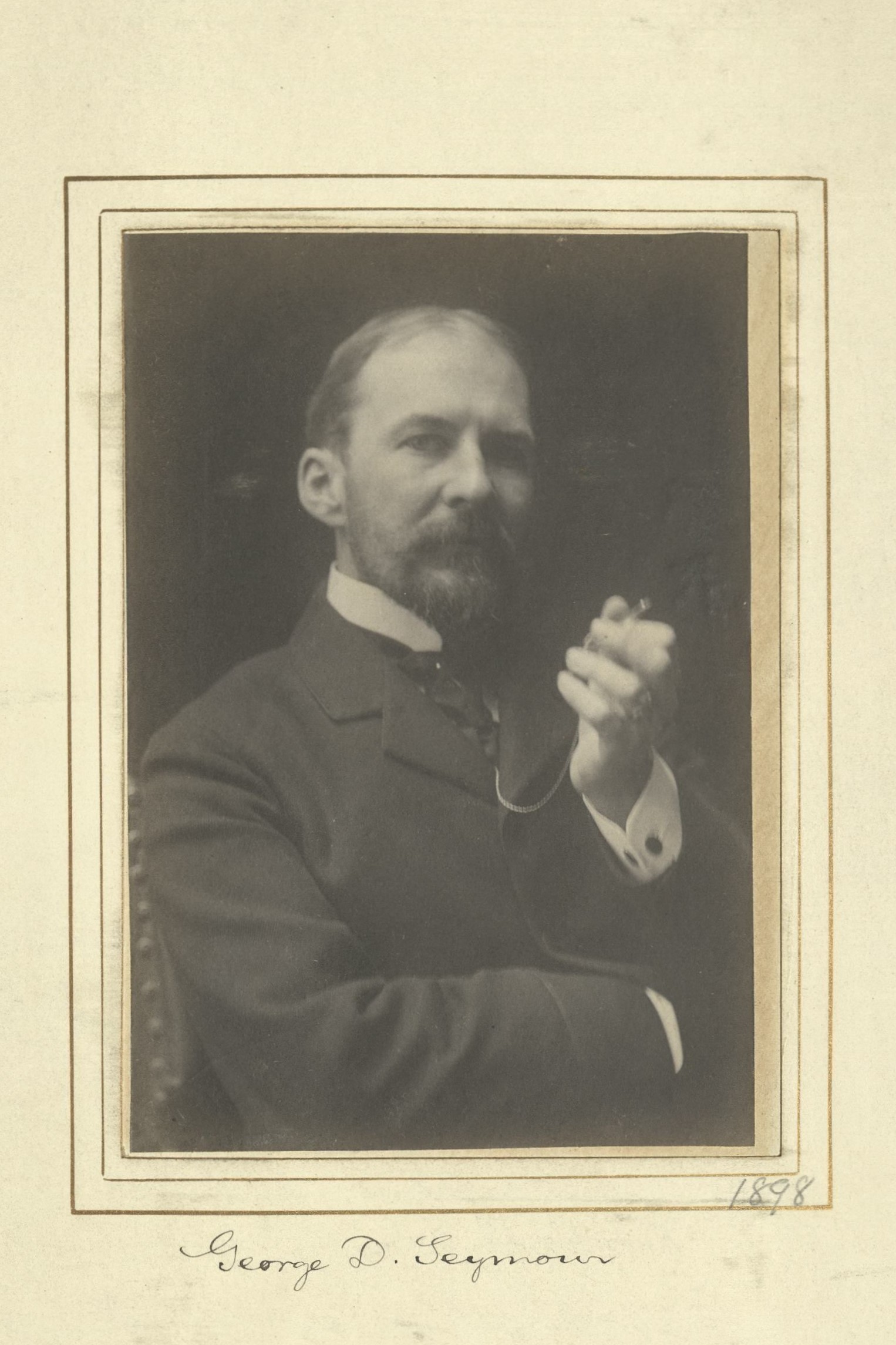

George Dudley SeymourLawyerCenturion, 1898–1945

George Dudley SeymourLawyerCenturion, 1898–1945 -

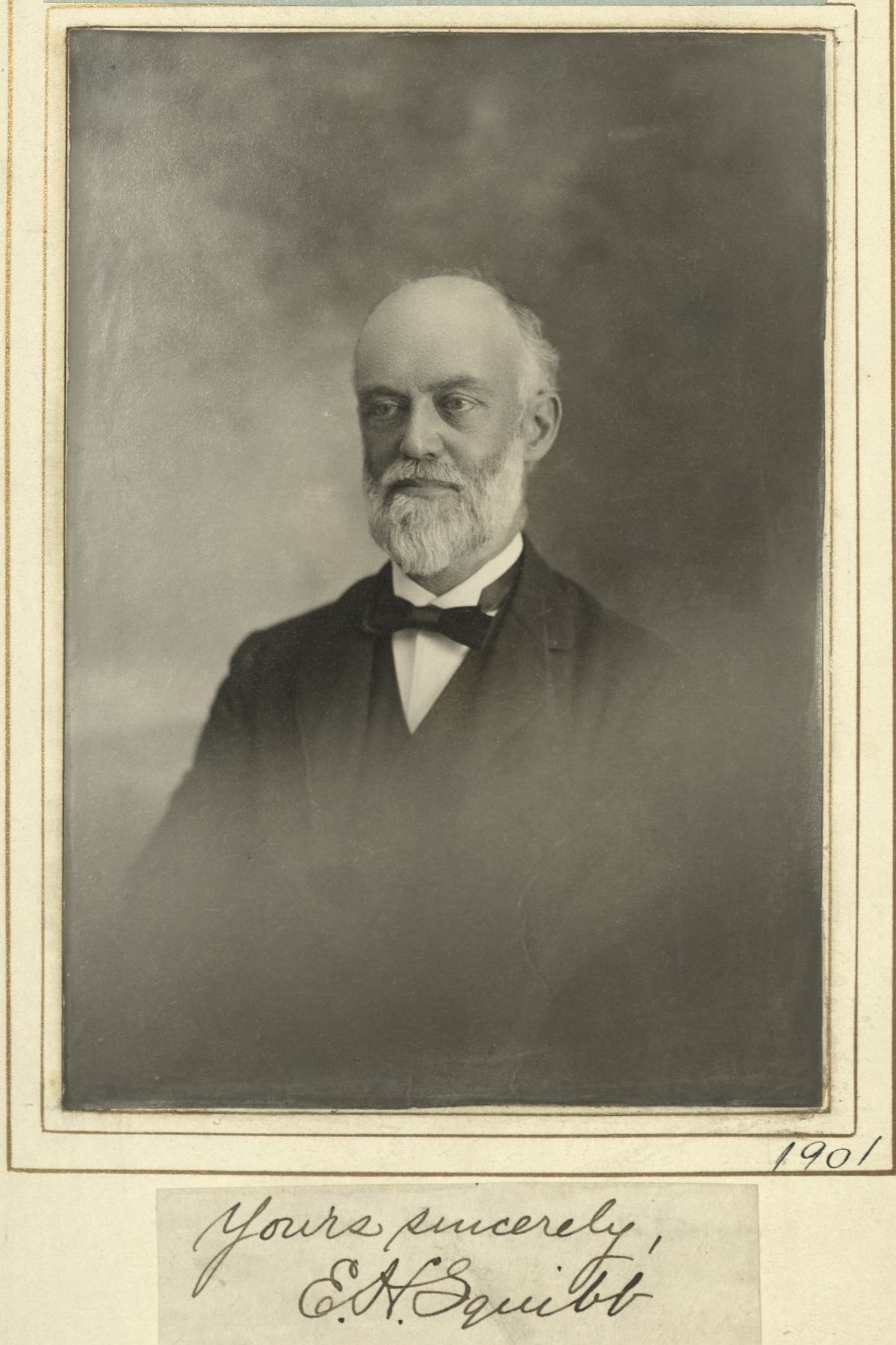

Edward H. SquibbChemist/PhysicianCenturion, 1901–1929

Edward H. SquibbChemist/PhysicianCenturion, 1901–1929 -

Richard S. StorrsClergyman/Civic AffairsCenturion, 1878–1900

Richard S. StorrsClergyman/Civic AffairsCenturion, 1878–1900 -

Hooper C. Van VorstLawyer/JudgeCenturion, 1859–1889

Hooper C. Van VorstLawyer/JudgeCenturion, 1859–1889 -

Walter A. WyckoffAuthor/ProfessorCenturion, 1899–1908

Walter A. WyckoffAuthor/ProfessorCenturion, 1899–1908