Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

Alfred Hoyt Granger

Architect

Centurion, 1909–1939

John Galen Howard and Cass Gilbert

Zanesville, Ohio

Roxbury, Connecticut

Age forty-two

Chicago, Illinois

Century Memorial

A Centurion painter who, fifty years ago, knew Alfred Hoyt Granger—architect of public buildings and vast railroad terminals—when they were art students on the Left Bank of the Seine, says: “We had adjoining rooms in the Hotel de France et Lorraine in the Rue de Beaune, conveniently near the bouquinistes of the Quai Voltaire. The hotel was frequented largely by Bonapartists—even the furniture was Empire. Granger, whom I liked from the start, had such good manners and was so invariably well dressed that he was somewhat looked down upon by the gang I ran with. The more broadminded among us were willing to attend the teas that he gave now and then in his room. His distinguished looking, white-haired mother presided over the tea table before a cheerful open fire. Much later, I used to see Granger at the Century, after he had built up a great architectural practice throughout the Middle West. I found him just as well-dressed, and with just as charming manners; but there was also an air of force and achievement that naturally was lacking in the old days of the Rue de Beaune.”

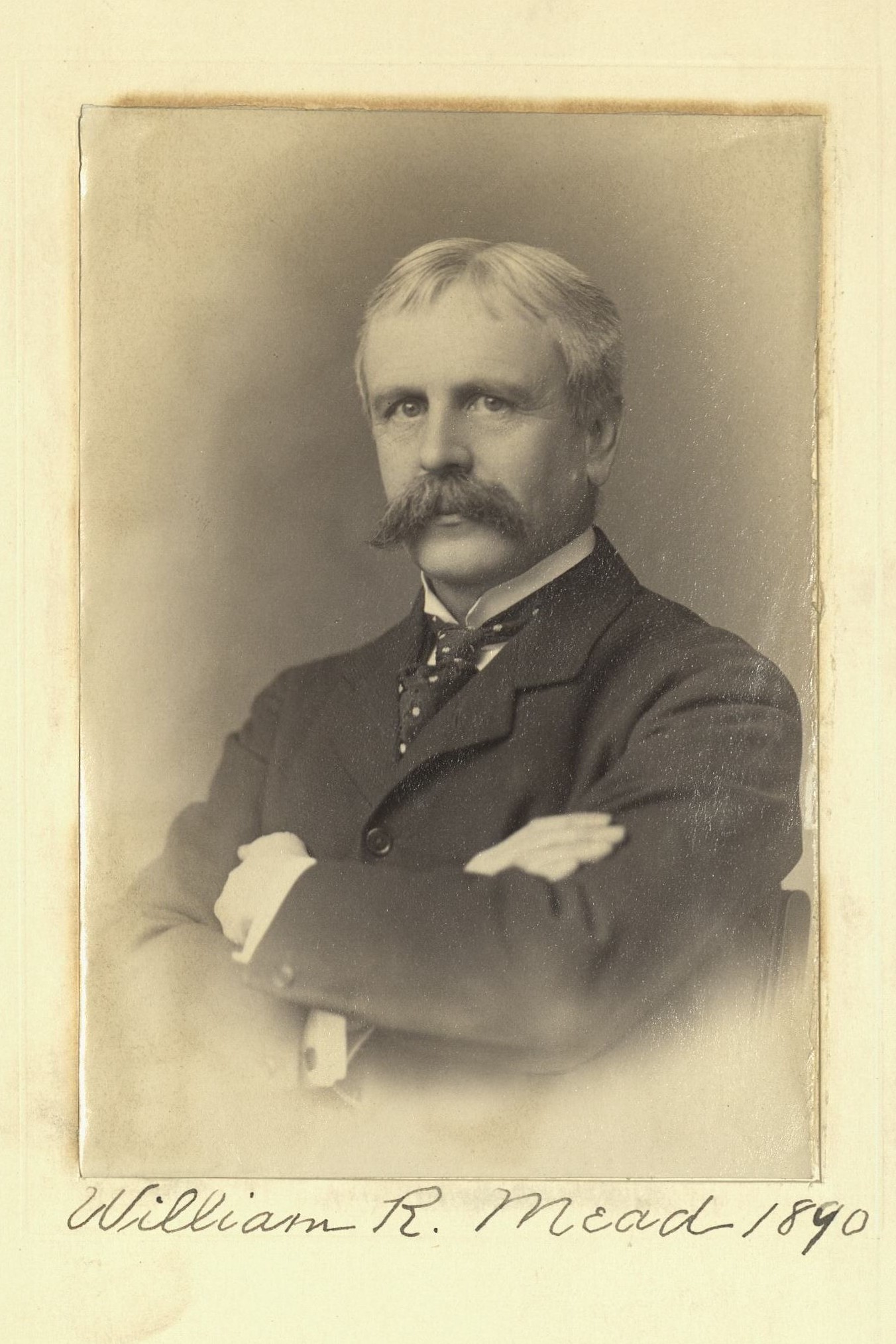

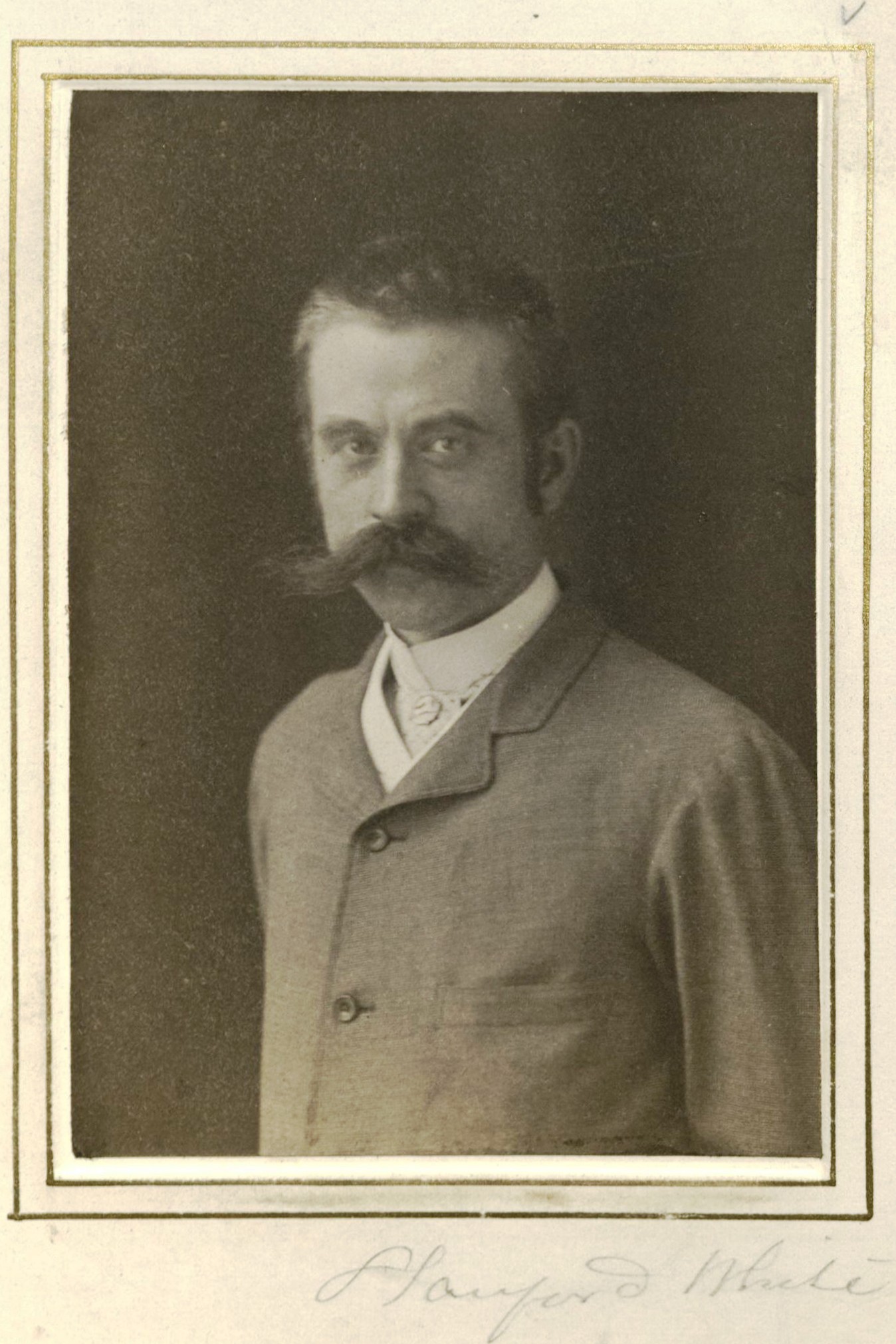

Granger’s leading interest, according to an architect member who knew him well, “was the advancement of the practice of architecture in this country.” To contribute to this advancement Granger published in 1913 a study of the life and works of Centurion Charles F. McKim. Our club-house, as we all know, was designed by McKim, Mead & White. Granger declared that the façade of the club deserved constant study by “young architects who sincerely wish to master the fundamental principles of proportion, composition and suitability. In this design there is no superfluous ornament. Every detail counts. . . . That all the enrichment is confined to the terra-cotta surfaces is worthy of attention. This material is never satisfactory when used in plain surfaces, as in the burning it almost invariably buckles and becomes uneven.” The decorative terra-cotta focuses the eye “upon what was intended to be the main feature of the design. The high basement expresses the fact that this floor is given up to rooms of secondary character yet of sufficient importance to demand light and air, and at the same time it is a most forceful factor in the beauty of the whole composition, as it lifts the charmingly proportioned loggia and the windows of the great rooms of the first story just the right height from the street.” These things in design do not just happen, but are achieved only “by careful study combined with faultless taste.”

“I had been three months in Granger’s office, and was doing my work to his satisfaction,” another Centurion testifies, “when one day, in answer to a question, I told him I wanted to get a bachelor’s degree at a certain school of architecture. He said, with a smile, ‘Go ahead.’ I told him I couldn’t possibly afford it. ‘Go ahead,’ he repeated, ‘and send me the bills.’ And I have reason to believe that he did this kind of thing—always by stealth—for a number of other young architects.”

Neither Granger’s blood nor his education was Teutonic, but in 1915 he wrote a pamphlet to prove that the Kaiser was not a brute. In 1916, when, as he estimated, ninety per cent of his countrymen were anti-German, he published in book form an argument in favor of keeping the United States out of war. He recommended using more of our wartime profits “to relieve the suffering caused by the war,” not only in Belgium, France, and England but in the countries allied with Germany. “Then, when we have convinced the world that we are really neutral and really great, we can carry our ministry of service farther and bend all our efforts to putting an end to the doctrine of hate that now dominates Europe.”

This trait of generosity, of warm concern for others, stood at the center of Granger’s character. The many Centurions who write of him all speak of his great charm as no more than the expression of a rarely friendly nature. A godfather and mentor to younger architects—“the greatest single factor of encouragement in my life,” writes one—Granger was the personification of hospitality, optimism and faith.

Geoffrey Parsons

1939 Century Memorials