Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

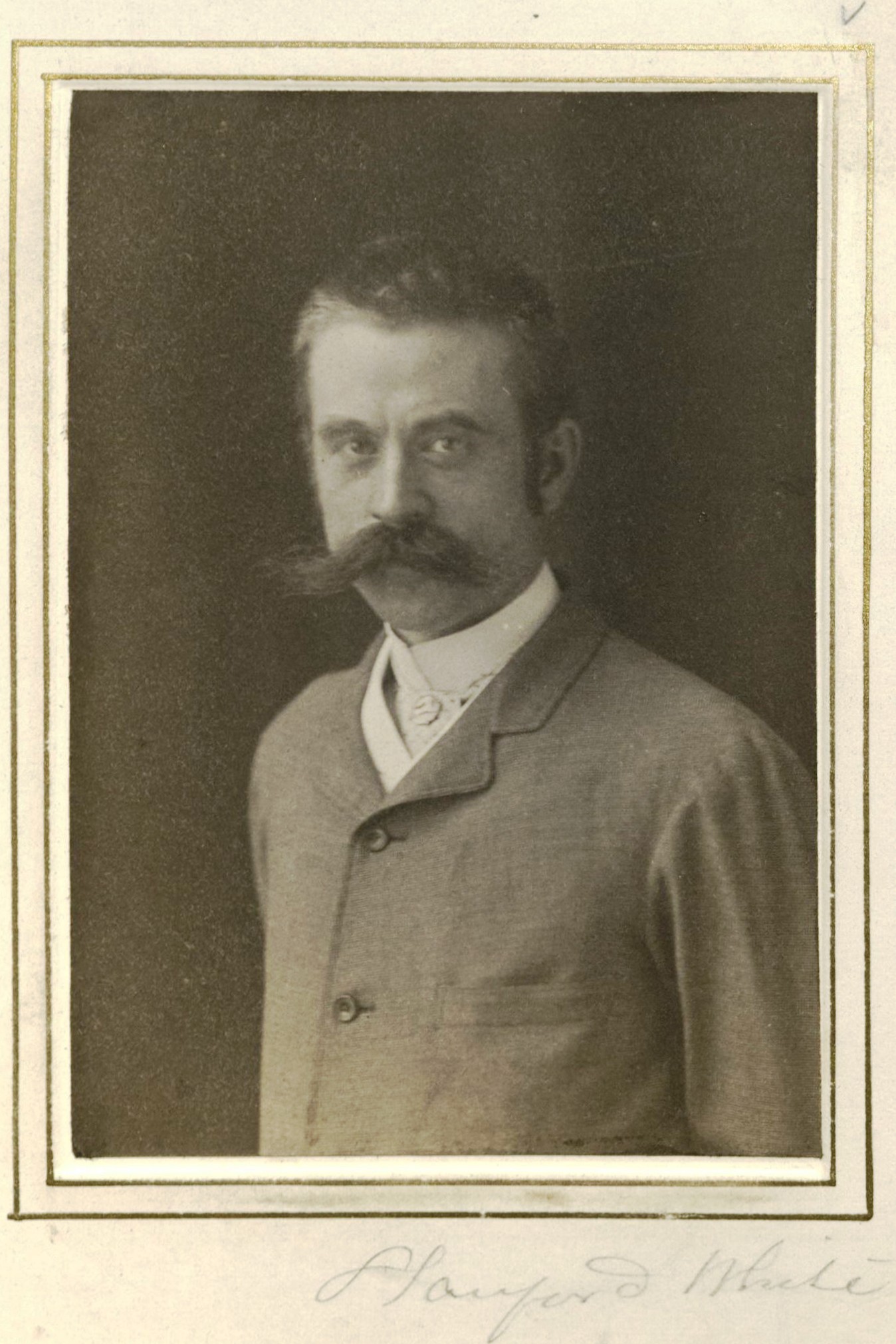

Stanford White

Architect

Centurion, 1886–1906

Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim

New York (Manhattan), New York

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age thirty-two

Saint James, New York

Archivist’s Notes

Father of Lawrence Grant White

Century Memorials

In the nomenclature of the sometimes vague and always fascinating realm of art it is not easy to find a term that exactly fits the gifts of Stanford White. An architect by profession he was, of marked achievement and acknowledged distinction, an architect whose work was at once conditioned and enriched by the instincts, the conceptions, even the methods of the painter. His monument is about us, and, day by day, as we and our successors live the continuous, always changing life of The Century, it presents its mute appeal to the most exacting. It expresses to us the manifestation of an opulent artistic nature, delighting in the joyous exercise of native power. The impression we who dwell with his work half-consciously receive prevails wherever the work exists. Born in 1853, an ancestry running back to the earliest colonial times, educated with specific reference to his future career, trained at first in the inspiring and adventurous school of Richardson, Mr. White, after four years of Europe, formed the connection with Messrs. McKim & Mead which lasted to the day of his untimely death, and which rounded out the rare combination of aptitudes in that firm so widely recognized and so highly appreciated. In the organized social life which has its centres in the clubs, his most distinctive work, besides our own home, was in the houses of the Metropolitan, the Lambs, and the Freundschaft. In business buildings the stamp of his peculiar gift is variously seen in the Knickerbocker Trust Building, in those of the famous silversmiths, the Gorham Company and Tiffany & Company, and in the delightfully quaint and effective Herald Building, holding its own by sheer force of beauty and adaptation to its uses among the climbing structures by which it has been surrounded. The latest struggle with like conditions still more trying is the new church of Dr. [Charles Henry] Parkhurst’s congregation, in its contrast with which the portico of St. Bartholomew’s discloses the range of Mr. White’s gifts. Still other phases of such disclosure are found in the numerous interiors for which he laid under tribute not only his own teeming fancy, but the treasures of Europe, particularly those of the later Renaissance. And still another phase of his endowment was manifested in the architectural work sustaining the statuary of Mr. Saint Gaudens, the Farragut monument, for instance, in our own city, with its combination of delicacy and audacity, and the monument to Mrs. Adams in Washington. Above all there is the congeries of structures known as Madison Square Garden, upon which, as a professional associate has remarked, he “let himself loose.” The great area covered, the spacious park adjacent, the peculiar site, making the lovely tower visible from such distances, presented opportunities which he seized with the utmost eagerness and skill. These are but hints of the singular scope and richness of Mr. White’s activities as an artist; they are strongly reinforced by the extraordinary beauty of his water-color drawings, made in connection with his more immediate profession, but of a sort that show the high rank he would have attained as a painter had he confined himself to the painter’s medium. In Club intercourse, which for The Century became rare with his multiplying occupations, Mr. White was genial, kindly, always interested and interesting.

Edward Cary

1907 Century Association Yearbook

White began his architectural career as the principal assistant to Henry Hobson Richardson. In 1878, he joined Charles McKim and William Mead to form McKim, Mead and White, which became an incubator for American architects.

White designed many outstanding buildings including Madison Square Presbyterian Church, the Villard Houses, the Washington Square Arch, Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square, and of course the Century, one of more than 50 club buildings his firm designed. Others include the Harmonie, Players, Union, the Knickerbocker, and the Metropolitan. The very social Stanford was himself a member of many of the clubs, and in 1886, he joined the Century, a club that years earlier had turned down his father.

White had a major influence in the “Shingle Style” of the 1880s, and the Newport cottages for which he is celebrated: the magnificent Rosecliff is a prime example. The firm also designed the Newport Casino, now the Tennis Hall of Fame. A number of outstanding buildings in the Berkshires—the inland Newport—that White designed are still standing, including the Berkshire Theatre (originally the Stockbridge Casino) and Naumkeag, which was the summer home of Joseph Choate. The impressive garden at Naumkeag, designed by Fletcher Steele, was added later.

With his wife Bessie, White took annual trips to Europe that combined pleasure and business. There he would buy antiques, paintings, and sometimes whole rooms for himself and for clients. Back home, White was known for his lavish and scandalous parties, which the adoring Bessie chose to ignore. White was attracted to beautiful women and, in 1906, this penchant finally did him in when he was shot and killed at the theatre rooftop of Madison Square Garden, which White had designed. The murderer was Harry Kendall Thaw, the jealous millionaire husband of Evelyn Nesbit, a beautiful young model, with whom White had once been intimate. The newspapers sensationalized the murder, and it became known as the Trial of the Century.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

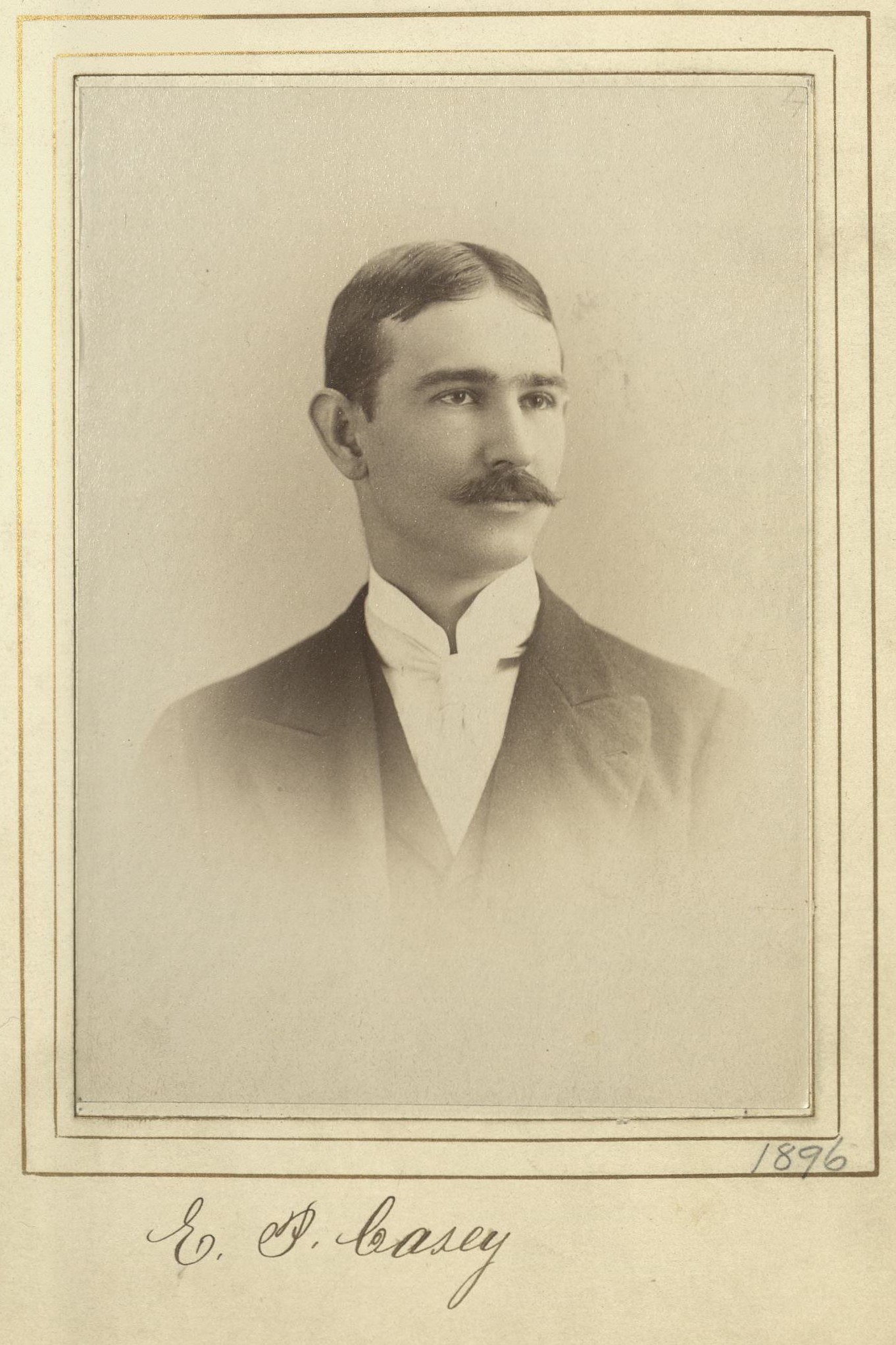

Edward P. CaseyArchitectCenturion, 1896–1940

Edward P. CaseyArchitectCenturion, 1896–1940 -

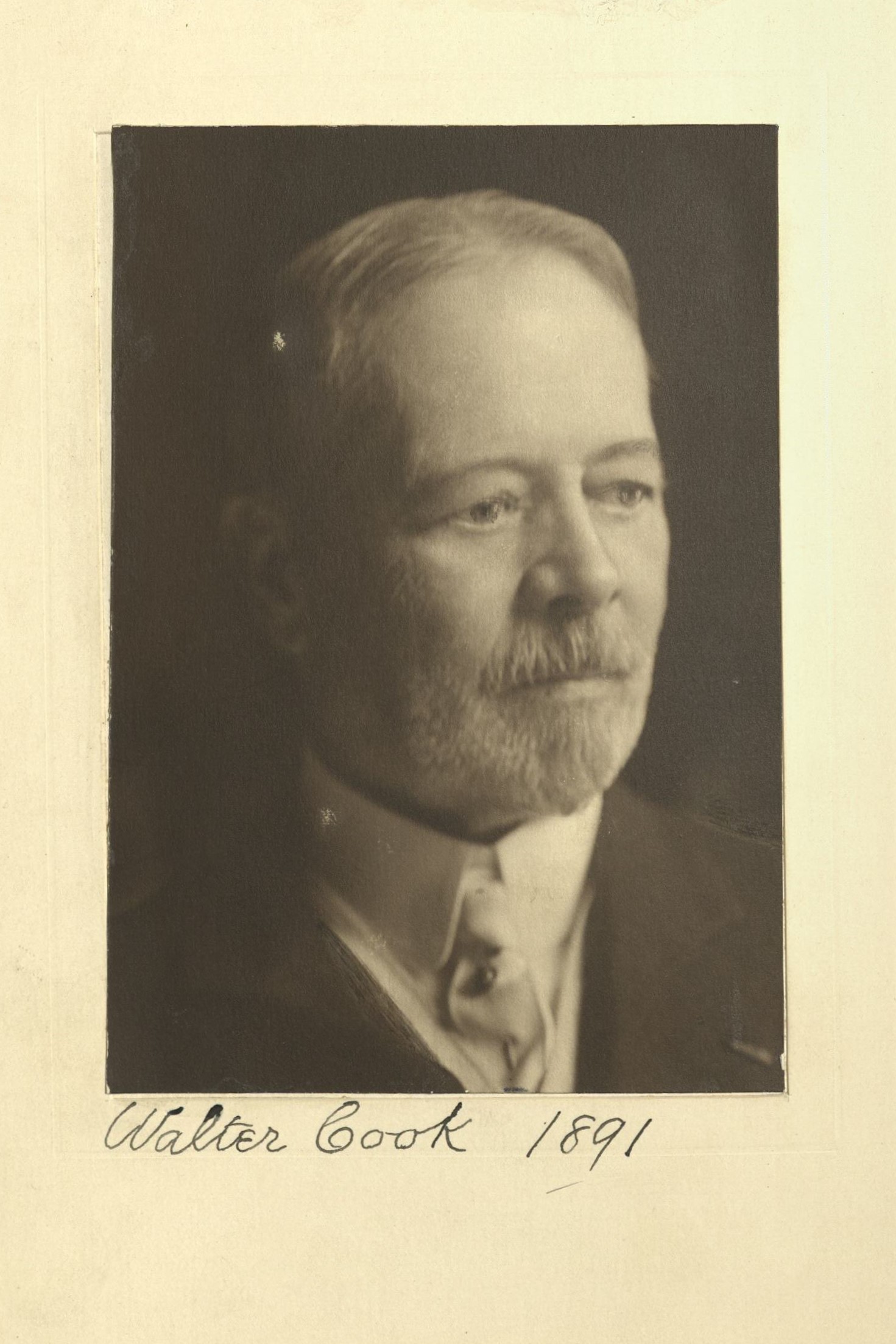

Walter CookArchitectCenturion, 1891–1916

Walter CookArchitectCenturion, 1891–1916 -

Burton N. HarrisonLawyerCenturion, 1892–1903

Burton N. HarrisonLawyerCenturion, 1892–1903 -

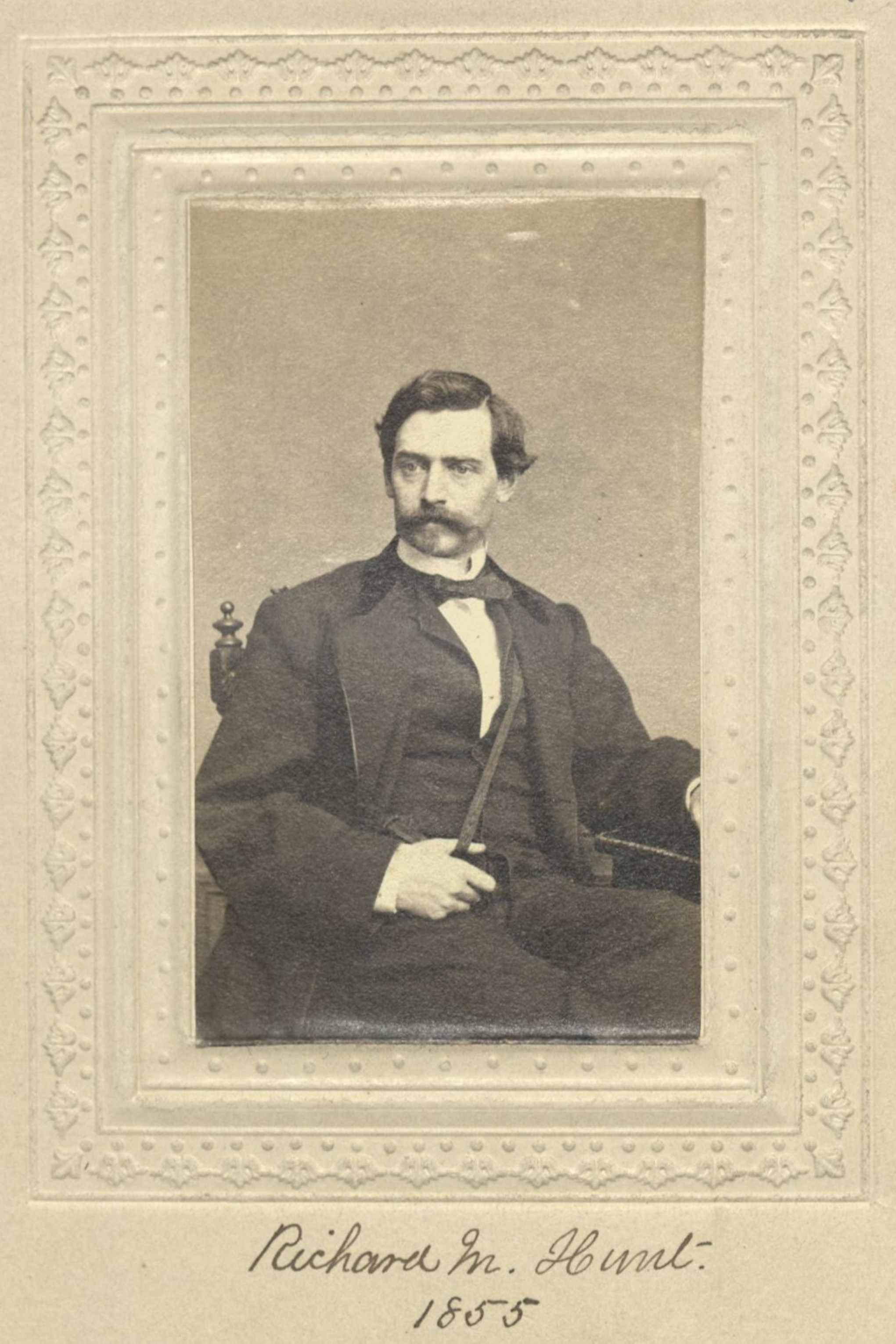

Richard Morris HuntArchitectCenturion, 1855–1895

Richard Morris HuntArchitectCenturion, 1855–1895 -

George Landon IngrahamJustice of Supreme Court, Appellate DivisionCenturion, 1898–1929

George Landon IngrahamJustice of Supreme Court, Appellate DivisionCenturion, 1898–1929 -

Charles Follen McKimArchitectCenturion, 1882–1909

Charles Follen McKimArchitectCenturion, 1882–1909 -

Augustus Saint-GaudensSculptorCenturion, 1886–1907

Augustus Saint-GaudensSculptorCenturion, 1886–1907 -

Charles H. SheldonMerchant (Marble)Centurion, 1893–1910

Charles H. SheldonMerchant (Marble)Centurion, 1893–1910