Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

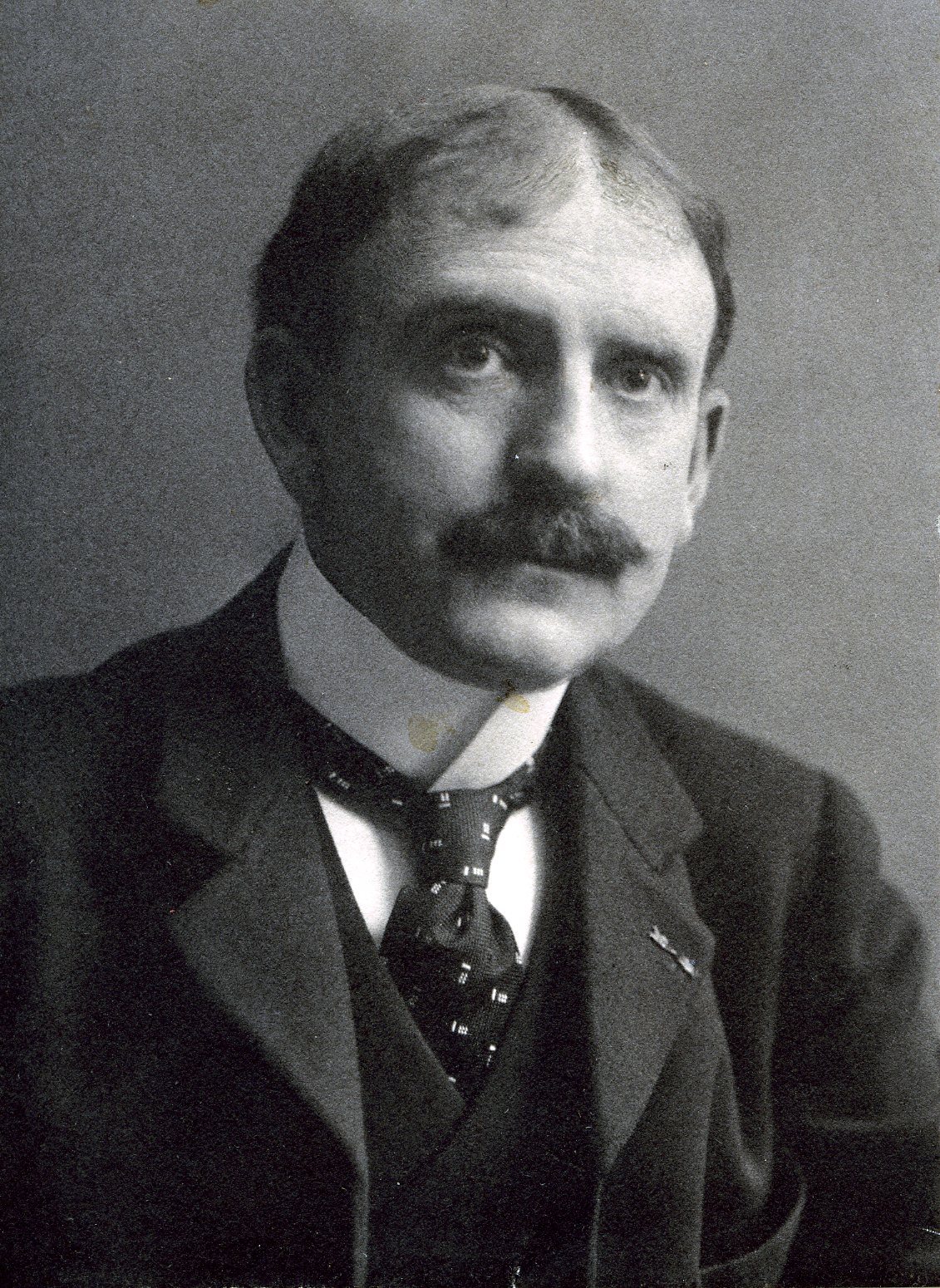

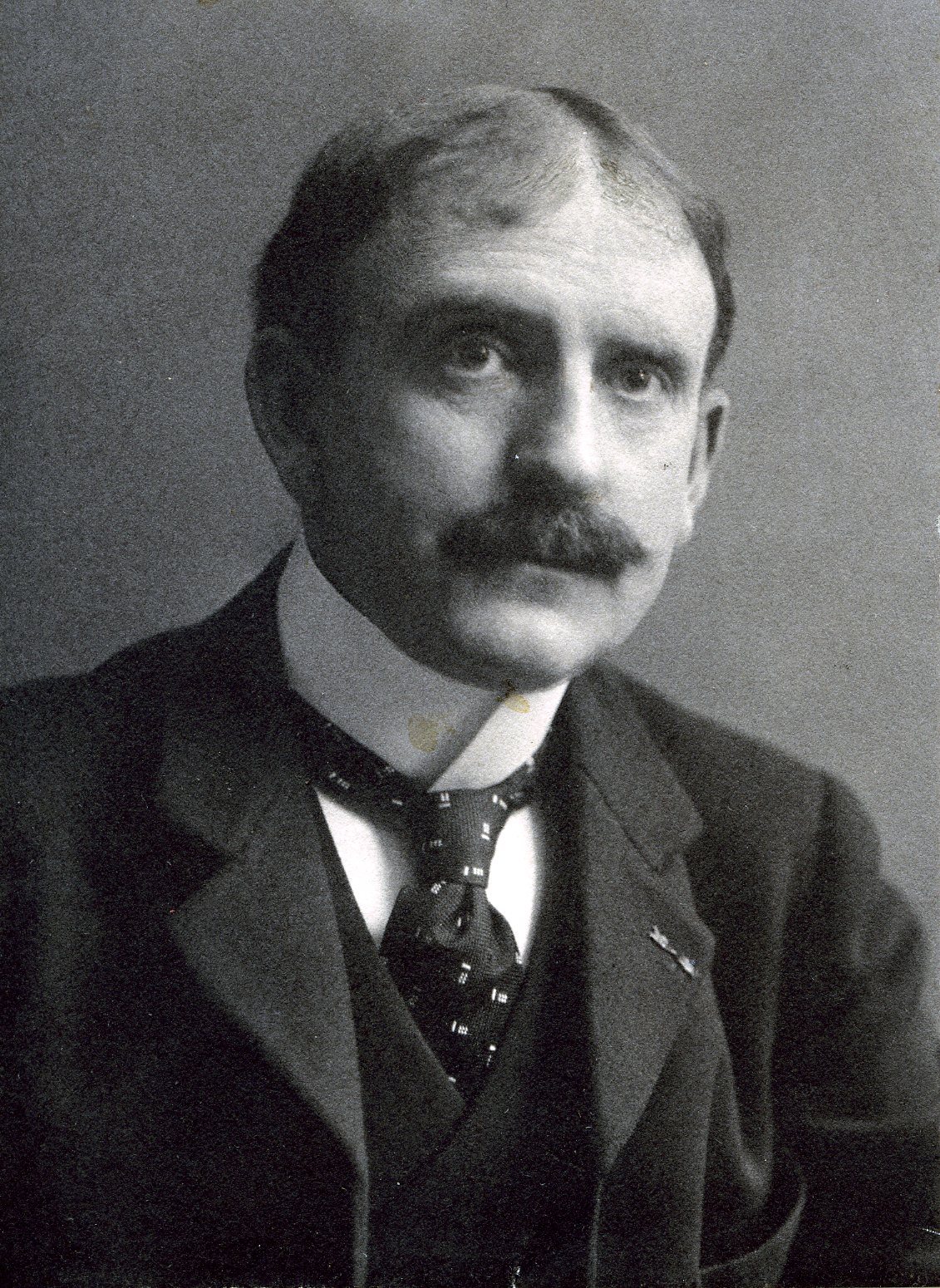

Francis Davis Millet

Artist

Centurion, 1884–1912

Sanford R. Gifford and James R. Osgood

Mattapoisett, Massachusetts

North Atlantic, At Sea

Age thirty-seven

East Bridgewater, Massachusetts

Archivist’s Notes

He died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic while en route from Southampton, England, to New York, the only Centurion to have perished in the catastrophe. (Henry Sleeper Harper, who was also aboard, survived.)

Century Memorial

When υβρις [hubris], the insolence of human pride, drove on to that disaster which chilled the heart of America and England, no name came more often to the lips of men than that of Millet—Francis Davis Millet. Few of that doomed company had touched life at as many points as he, or had experienced such diverse phases of it in so many lands; certainly none had met its chances with happier, braver heart and readier faculty, or in the fullness of a generous human nature had appealed to more kinds of men.

And withal, he was simple and moved by heroic singleness of motive; for it is simple and heroic to act and do quickly what comes to hand, without fearing the past, the present, or the future. The diversity of Millet’s career lay on the surface; at bottom it was one, issuing from the impulse and faculty of action and the gayety of living and doing.

How soon the boy began to live and work fearlessly! Born in Mattapoisett, Massachusetts in 1846, when the Civil War came, he enlisted as drummer, went through the war, and emerged as surgeon’s assistant. Then he entered Harvard, worked heartily, and supported himself by taking photographs. He took up newspaper work, first on the Boston Daily Advertiser. The impulse to paint was as strong in him as that toward journalism, and, in spite of his intervening triumphs as war-correspondent, was to conquer in the end. In 1871 he crossed the ocean to enter the Royal Academy in Antwerp, where he roomed with George Maynard, won the prizes for painting in successive years, yet kept himself a universal favorite by the humanity which was his.

Many knew of Millet, and while still at Antwerp, he was appointed secretary of the Massachusetts Commission for the World’s Fair at Vienna. In the meanwhile, he had not ceased to earn his bread by corresponding for American papers and, being a quick linguist, he added an Antwerp paper to his list. Then back to America, much interested in the Centennial Exposition, and helping John La Farge decorate Trinity Church in Boston.

The Russo-Turkish War offered the perfect chance for Millet to prove himself as writer, artist, man. He went as war-correspondent for the New York Herald, and as the war advanced, the London Daily News, learning of his gifts, made him the successor of Archibald Forbes, invalided through fever. Millet’s quick heroic qualities came into play, as he cared for the wounded under fire, even amputating a limb, and made himself invaluable to the officers from Skoboleff down, receiving decoration after decoration for his humanity and bravery.

After the venture of this war, Millet’s painting throve apace. He worked for a while in Paris, where in 1879 he married Elizabeth Greeley Merrill, and St. Gaudens made a relief portrait of him. Then much time was spent in England, above all at that famous American discovery, the old village of Broadway in Worcestershire. There he painted many of his best easel pictures. He was called in 1892 to the Directorship of Decoration of the Columbian Exposition at Chicago, and with the acceptance of this call he entered upon his great career as mural decorator and organizer of decoration. His work at that exposition, and the work of other American artists under his general direction, formed the grandiose inauguration of American mural painting.

Time fails to follow Millet’s work in the public buildings of Baltimore, St. Paul, Jersey City, Cleveland, and Washington. It was interrupted by the Spanish War, when he served the London Times as war-correspondent in the Philippines. Quite recently he was chosen for the task of reorganizing and adapting to new conditions the combined American Academy and School of Classical Studies at Rome. He was on a voyage home from there when it came to him to die; and we know enough of the last scene to know that nothing in his life better became Frank Millet than his conduct when leaving it.

Henry Osborn Taylor

1913 Century Association Yearbook

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

Charles Francis AdamsHistorianCenturion, 1912–1915

Charles Francis AdamsHistorianCenturion, 1912–1915 -

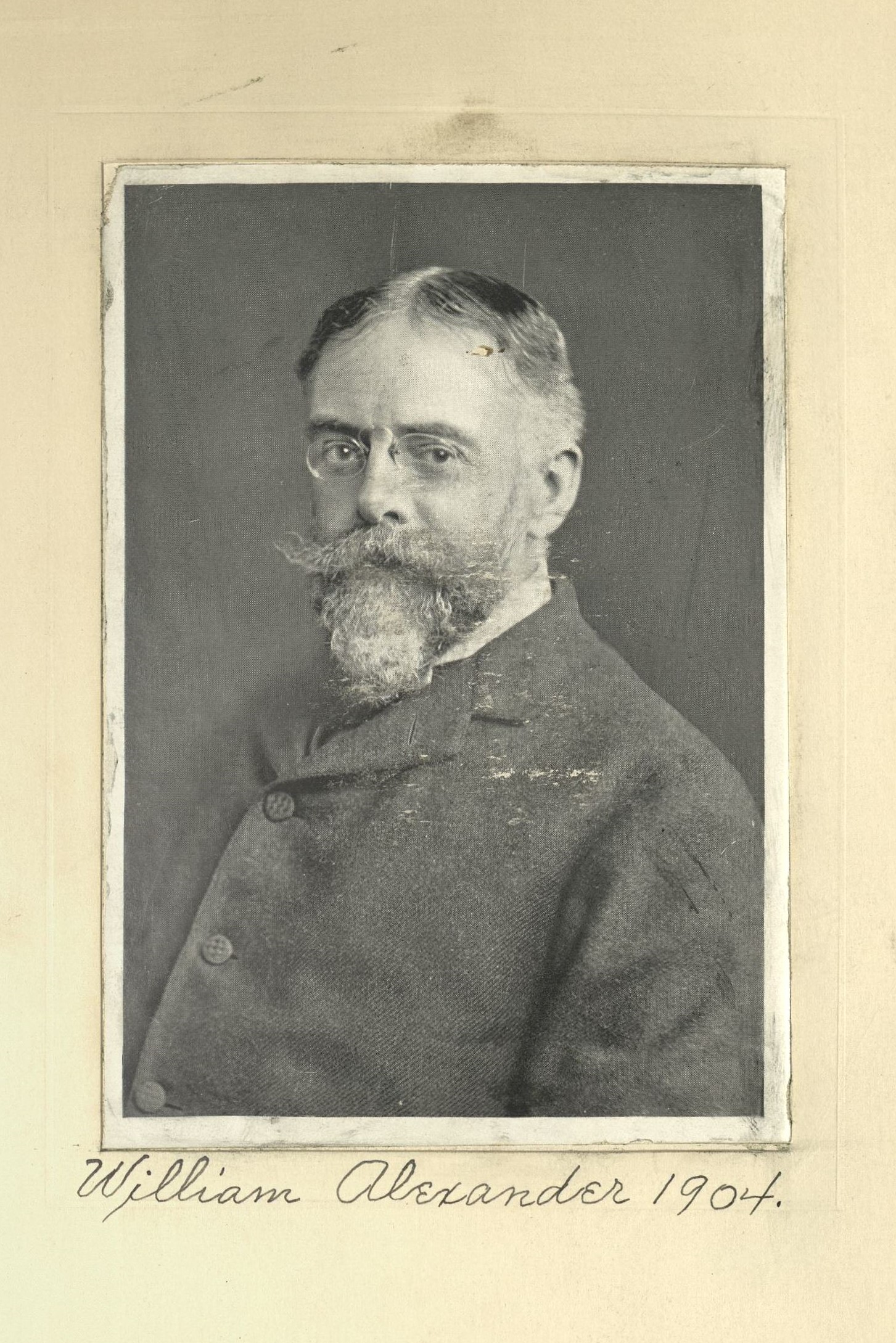

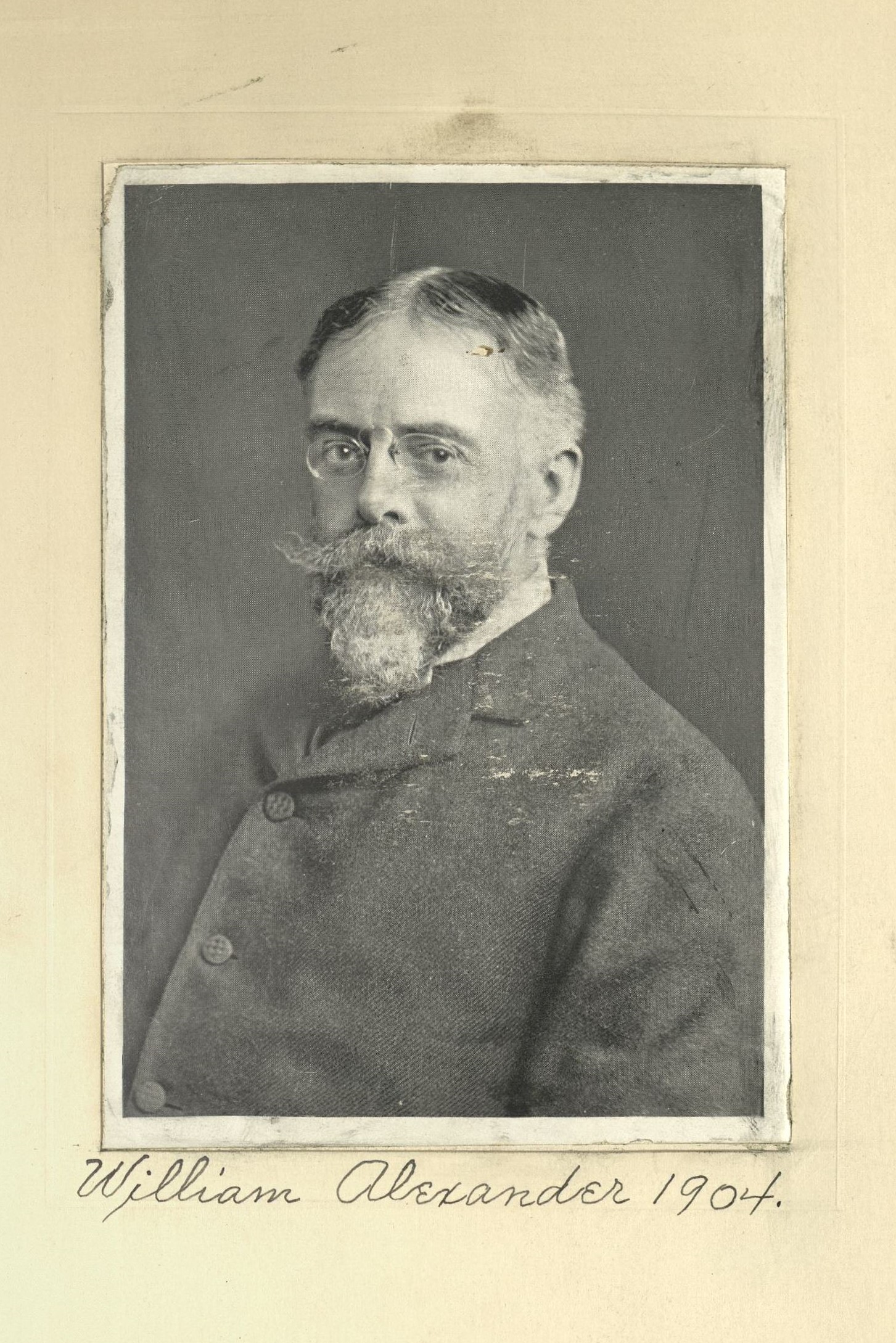

William AlexanderSecretary, Equitable Life Insurance CompanyCenturion, 1904–1937

William AlexanderSecretary, Equitable Life Insurance CompanyCenturion, 1904–1937 -

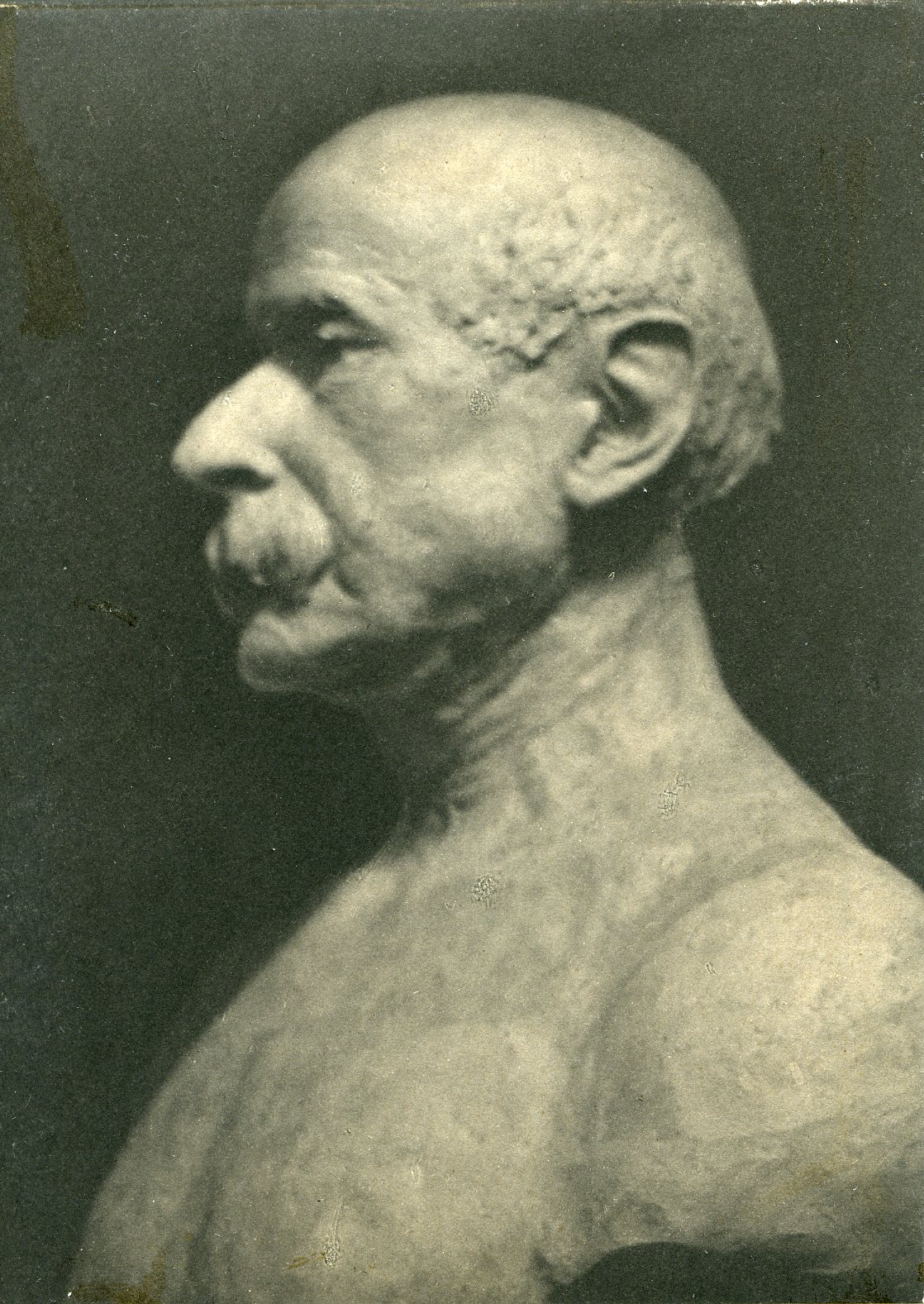

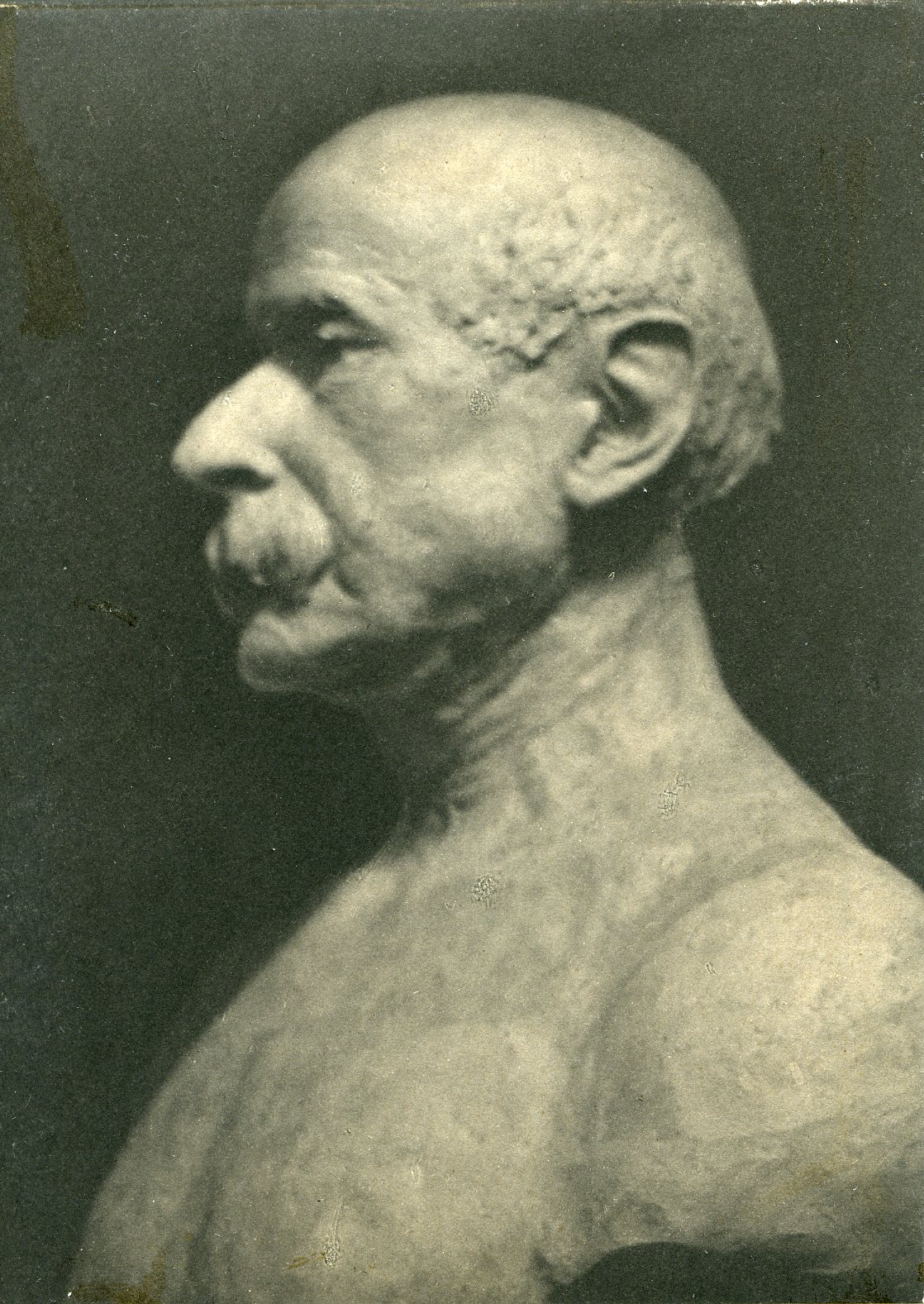

Sanford R. GiffordArtistCenturion, 1859–1880

Sanford R. GiffordArtistCenturion, 1859–1880 -

Francis LathropArtistCenturion, 1892–1909

Francis LathropArtistCenturion, 1892–1909 -

Walter MacEwenArtistCenturion, 1906–1943

Walter MacEwenArtistCenturion, 1906–1943 -

Gari MelchersArtistCenturion, 1911–1932

Gari MelchersArtistCenturion, 1911–1932 -

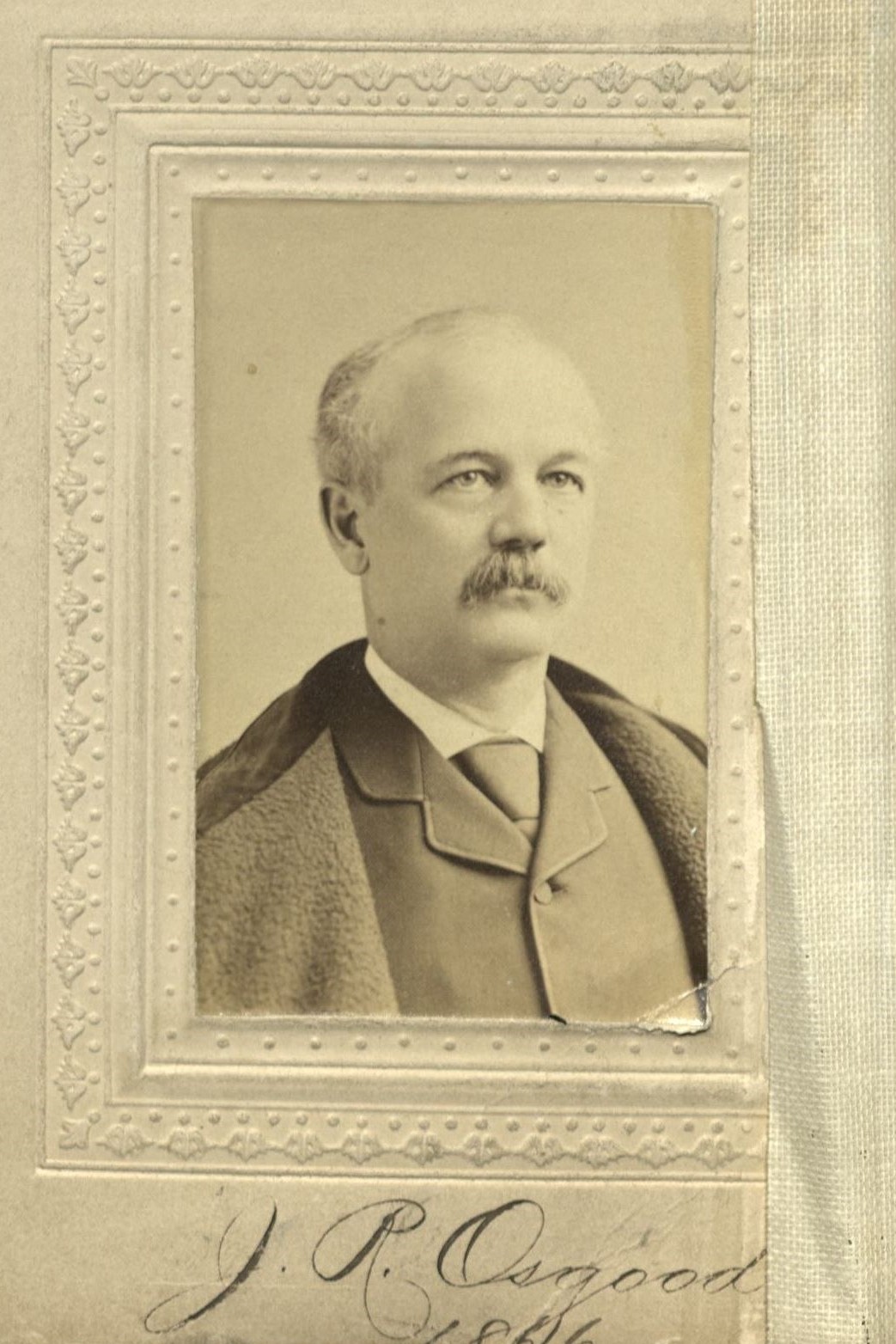

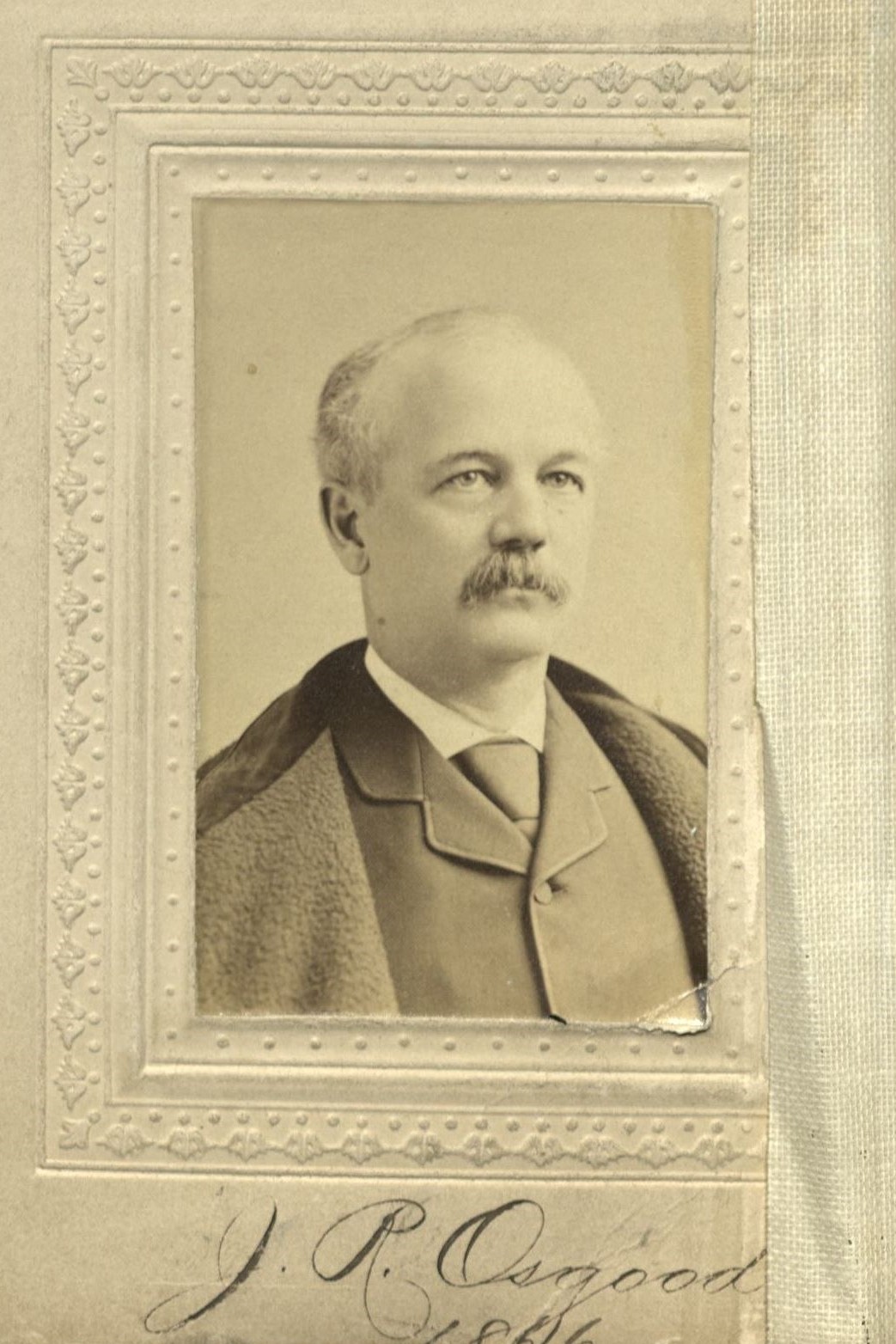

James R. OsgoodPublisherCenturion, 1866–1892

James R. OsgoodPublisherCenturion, 1866–1892 -

Evert Jansen WendellMerchantCenturion, 1892–1917

Evert Jansen WendellMerchantCenturion, 1892–1917