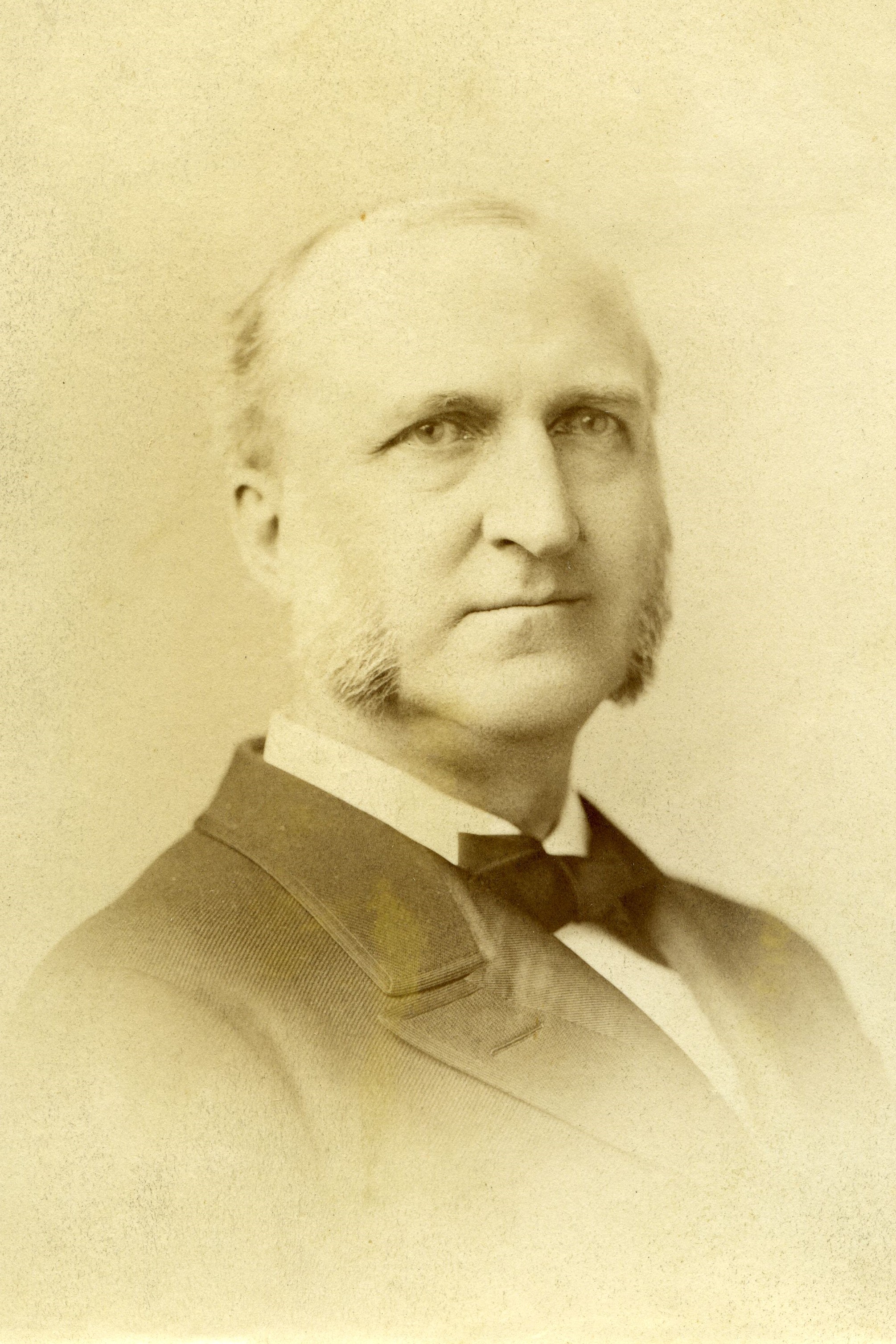

Railroad President/U.S. Senator

Centurion, 1886–1928

Born 23 April 1834 in Peekskill, New York

Died 5 April 1928 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Hillside Cemetery , Cortlandt Manor, New York

, Cortlandt Manor, New York

Proposed by Augustus R. Macdonough and Francis F. Marbury

Elected 6 November 1886 at age fifty-two

Archivist’s Note: Son-in-law of William Hegeman

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

Chauncey Depew remarked of his own career: “When I look back over sixty-five years on the platform in public speaking, and especially when I consider my own pleasure in the efforts, the compensation has been far greater than the attainment of any office.” With this retrospective view the public of those palmy days would readily have agreed. The platform with which they associated Depew’s cheerful personality was not the formal stage of political conventions or patriotic centenaries, but the long head-table at Delmonico’s or the Waldorf, from whose apparently solemn array of celebrities the scintillation of wit and epigram began when chairs had been pushed back, napkins tossed beside the coffee cups and cigars lighted up to introduce the real business of the evening. Few people can recall Depew as United States Senator from New York, fewer as President of the New York Central Railway. His occupancy of each office appeared even to his contemporaries as a complimentary distinction, and Depew’s own reminiscence of those episodes in his life was usually colored by the humorous side of them. Of his political career he recalled with the most appreciation the Southern Senator who denounced him as an emissary of the railroad interest, unscrupulously quartered on the Capitol, and then explained personally that he did not really mean it, but “I thought you would not care, because it won’t hurt you but it does help me in Arkansas.” What particularly stuck in his mind in connection with the New York Central episode was Wayne MacVeagh’s expression of disquiet, when presiding at the Yale Association’s testimonial dinner, that his friend Chauncey should have been elected president of the most unpopular railroad in the country—coupled, however, with the reassuring prophecy that, after all, Depew would probably “make it the most popular of our railroad corporations, because he will bring its stock within reach of the poorest citizen.”

This kind of friendly tribute was quite in Depew’s own vein. The recollection which mention of his name brings to the New Yorker’s mind is of an era in the city’s life which is now a tradition of the past. After-dinner oratory in its prime is as far behind us as the day of fast driving on the Speedway, almost or quite as far as the Saturday afternoon bicycle procession on the Riverside or the Business Men’s parade up Broadway in the week before election. It may not have been the Age of Innocence, but at least it was not the Sophisticated Age. When the postprandial wits of the nineties flourished, the Yale and Harvard dinners were events of a season. The day of the radio had not come. Speakers addressed an audience, more or less convivial, whose response was visible, immediate and provocative, not a shadowy host of “listeners-in” with whom contact was less intimate than with the names in the directory. The exchange of compliments between those seasoned masters of epigram provided an invariable first-page story for the next morning’s newspaper.

They gave no quarter to one another. Mr. Evarts, following a speaker who had wondered why the coatings of the stomach, which digested everything else, did not digest themselves, quite instinctively assured the audience that he always removed the coatings of his own stomach before attending a Harvard dinner. It was altogether in the spirit of the occasion that General Porter, having been introduced as the man from whom, if you dropped a twenty-dollar dinner in the slot, up comes the speech, should have rejoined that when one of the chairman’s speeches is dropped into the slot, up comes the dinner. Whether we have grown to be a more serious people in these later days, so profoundly engaged in solving problems that we have no leisure for the humorous view of things, whether the diner-out has become more fearful of being bored than hopeful of being entertained, or whether the race of after-dinner wits has itself died out, at all events we live in another period.

Those were the occasions on which Depew came into this own. When he said in after life that the audience of the present day “prefers epigram to argument, humor to rhetoric,” and recalled how his own orations used to be “the by-product of spare evenings and Sundays taken from a busy life,” he did himself and his old-time audiences injustice. It was the spontaneity of the convivial wits of three or four decades ago which made them what they were. But no reminiscence of Depew would be at all complete which did not emphasize his incurably cheerful view of the human scene. The longer he lived, the longer he wished to go on living in this agreeable world, and perhaps the greatest disappointment of his own life was that he came so close to passing the century-mark without succeeding.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1929 Century Association Yearbook