Merchant

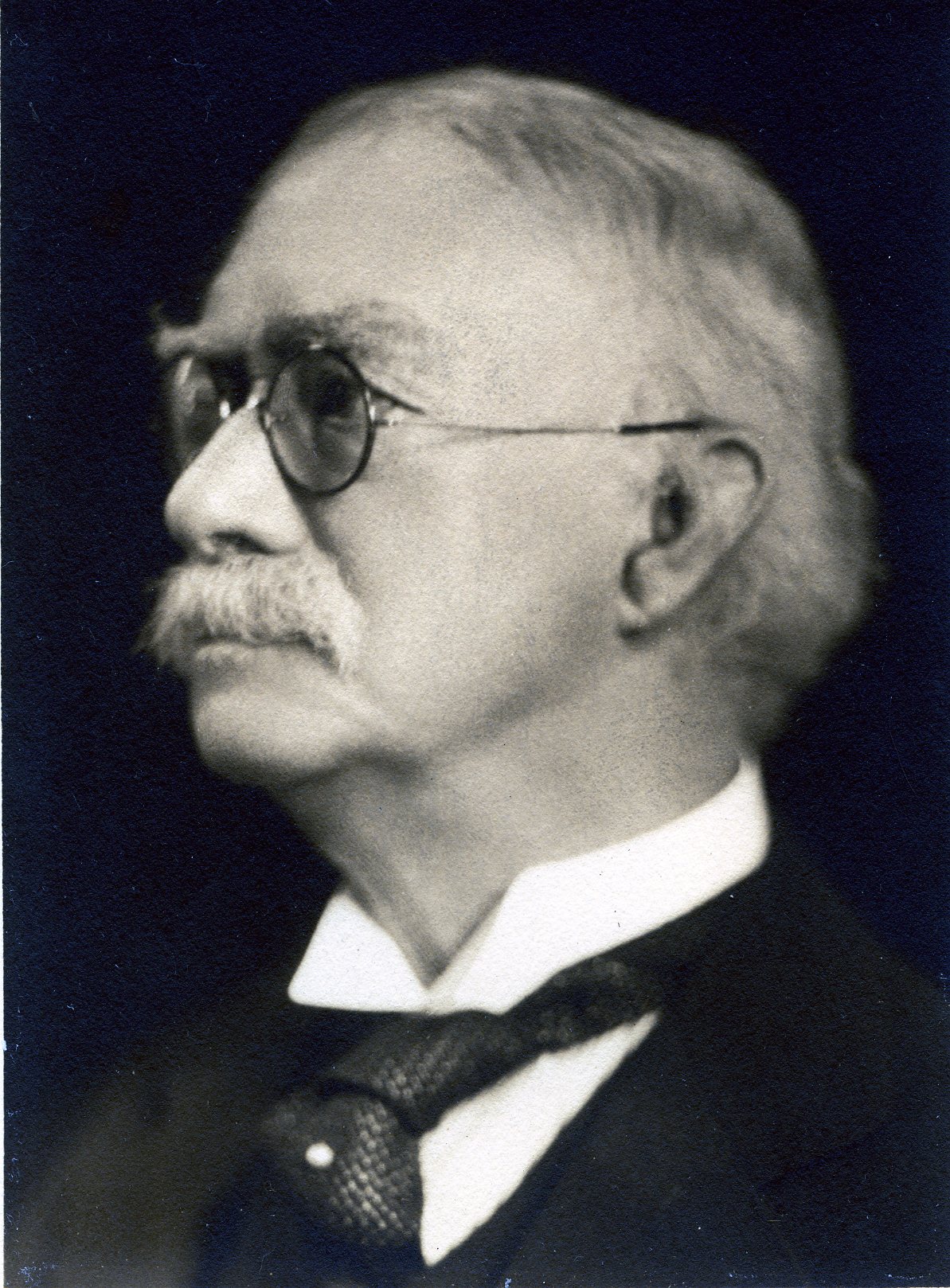

Centurion, 1897–1932

Born 10 February 1842 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 3 November 1932 in Summit, New Jersey

Proposed by Edwin W. Coggeshall and Frederic Cromwell

Elected 1 May 1897 at age fifty-five

Century Memorial

When old age has separated members of the Club from active participation in the affairs of life, when fellow-Centurions of their own day and of their own close acquaintance have answered to the last roll-call, when Club-room groups must seem to be made up entirely of a much younger generation, some of them withdraw from Club affiliations as they had already retired from business. Their faces are seldom seen in reading-room or library. They keep their names on the membership list, but it is mostly because of association with the past. Happily for the Century, these are the exception, not the rule. The younger Centurion who left the lunch-table without exchanging a cheerful word with James William Cromwell or Algernon Sydney Frissell felt that he had somehow missed the spirit of the place. Few Centurions passed the door of the Graham Library if, as was apt to happen almost daily up to the very last, these Nestors of the Club were at their familiar posts. When the younger men drew up their chairs around the veteran fellow-clubmen, the conversation instantly grew cheerful over events and personalities of the day.

Cromwell was one of the old-time New York merchants. His active business experience ante-dated the Civil War. Long before the “panic of 1929” and the “hard times of 1932” had become the community’s chief preoccupation, he had lived through the ups and downs of half a dozen trade depressions and through the subsequent epochs of American prosperity. Like the rest of us, he saw our present vicissitudes and our present problems with the eye of the present day, sharing in the alternation of despondency and reviving hope; but it was always in a spirit of absolute confidence in the country’s future—a confidence which his own experience of nearly a century abundantly reinforced. But Cromwell’s mental background was a good deal more than this. With a fellow-enthusiast he could talk as readily of Shakespeare as of events in trade or on the markets. His memory of the masterpieces of English literature was extraordinary. When his eyesight failed him, it was as if he had photographed the printed page upon his mind. One day a guest from London, whose name no one had caught, joined the Graham Library circle, and conversation turned to the perennial dispute over Hamlet’s eccentricities. Cromwell and the visitor drew opposite interpretations; each quoted a passage from the play to support his view. Cromwell followed with a telling series of textual utterances in point by the Danish prince, and in the end the Londoner laughingly admitted that the weight of evidence was on Cromwell’s side. To the modest Cromwell’s great confusion, it presently developed that the guest was Granville Barker, who had played every part in “Hamlet” except Ophelia and the Queen. But literature was only part of our old Centurion’s avocations. He loved to visit the flowers which he had cultivated, even when he could no longer see them, and it is one of the Century’s pleasantest traditions that the colorful floral decorations, which the club’s luncheon or dinner table were never allowed to lack, were sent from Cromwell’s garden.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1933 Century Association Yearbook