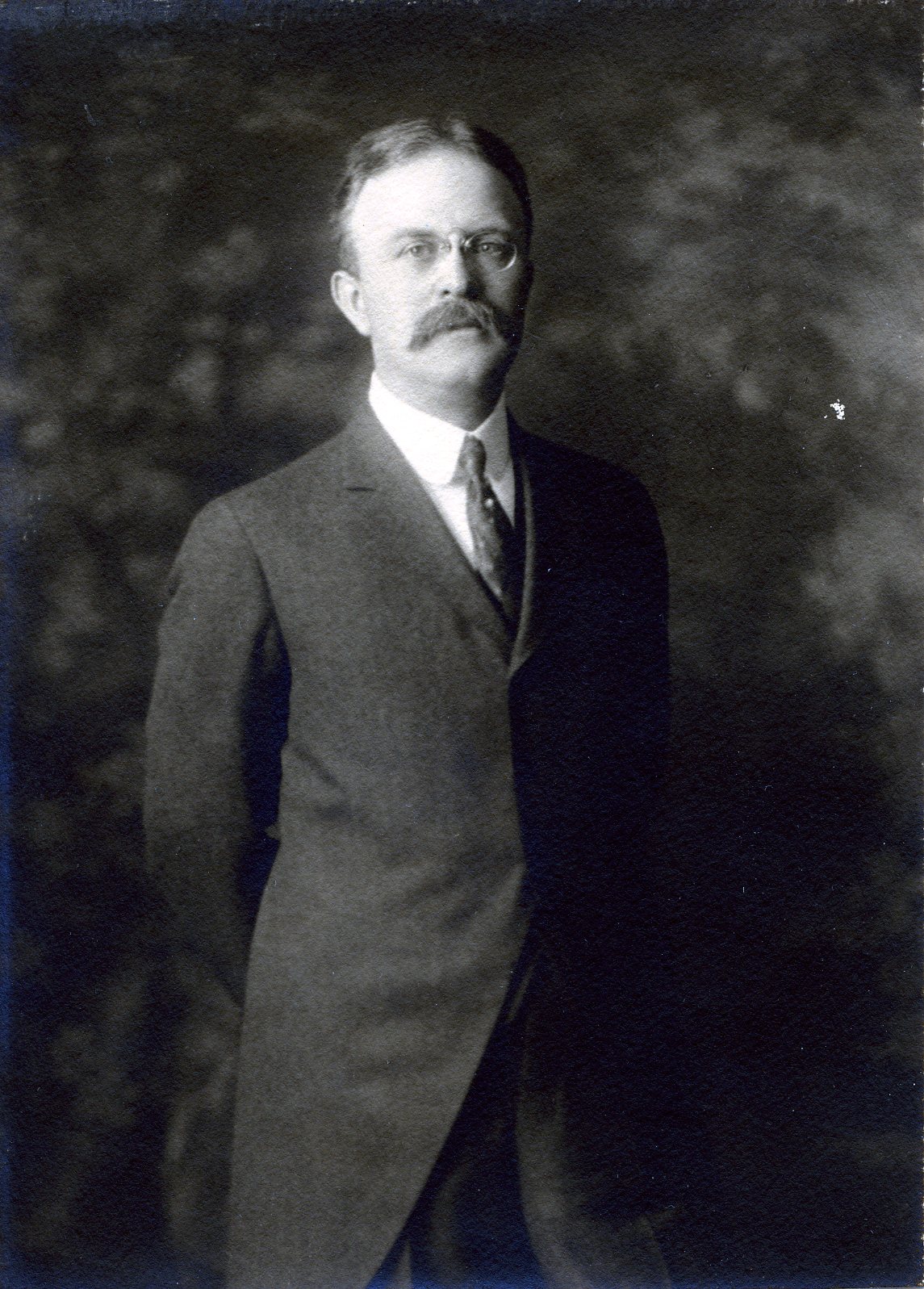

Editor

Centurion, 1914–1949

Born 13 March 1872 in Wiesbaden, Germany

Died 1 October 1949 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Sleepy Hollow Cemetery , Sleepy Hollow, New York

, Sleepy Hollow, New York

Proposed by Hamilton Holt and George A. Plimpton

Elected 2 May 1914 at age forty-two

Archivist’s Note: Grandson of (nonmember) William Lloyd Garrison; father of Henry Hilgard Villard

Seconder of:

Century Memorials

Oswald Garrison Villard. [Born] 1872. Editor. A member of the Century for 35 years.

He sat here in the front row, right under the lectern, every year I have read the Century Memorials; but he is missing tonight and I must read his. Mr. [C. C.] Burlingham, the happily indestructible, with his long perspective on man-conformity, should have written it: it does not become a youngster of 55 like me to assess Oswald Garrison Villard. But I shall do the best I can—as I must, and as, in affection, I want to do.

The motto of our Nation—and, fully understood, it is in one sense our proudest heritage—is E Pluribus Unum: we are one made out of many, we are States and other minorities welded together by our common ideals—all protected by our Bill of Rights. That protection extends to the tiniest minority of all, the conscience of one individual. Our system of law cherishes that individual conscience, knowing that if it be trampled all is trampled, knowing that if its freedom be curtailed Buchenwald is around a very near corner.

I say that we know this, and, of course, we do; and, of course, if any governmental power proposed openly to take away this freedom, that power would be suppressed. But particularly in times of stress there is nibbling at the edges and always eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.

Oswald Garrison Villard was eternal vigilance. But he was more. He saw clearly that the guarantees of our Bill of Rights are guarantees imperfectly realized: that there is much room in which to move toward perfection; and, as a servant of great human causes, always he wanted impatiently to move and to move fast. And he saw even farther. He saw that, not only must we preserve the ideals of freedom we have inherited but also we must discover new goals to human betterment and move toward them: that there are new political truths to be discovered which must be discovered if our children are to be as proud of their heritage as we are of ours.

He was sharp and he was brave. He was scornful and he was cantankerous. He knew black solitude and he knew despair. He knew hope and he knew defeat. He never strayed from his ideals nor his integrity; his road was always straight: he trusted his head and his heart and he spoke with power; and thus it will be that, a hundred years from now, men who never heard his name will move to the measure of his idealism and his thought.

He was a great and good man, this editor of the old Evening Post and of The Nation. I know that his maternal American grandfather, William Lloyd Garrison, is proud of him in Heaven; and I hope it is not too much to hope that his paternal German grandfather, the Bavarian judge who exiled his son for political non-conformity, may now have some glimmerings that a few Oswald Garrison Villards allowed to function in Germany, might have saved that country and the world.

Such, no less, is the measure of the importance of Oswald Garrison Villard.

Source: Henry Allen Moe Papers, Mss.B.M722. Reproduced by permission of American Philosophical Society Library & Museum, Philadelphia

Henry Allen Moe

Henry Allen Moe Papers, 1949 Memorials

Villard was born in Germany, while his parents were on a vacation. He graduated from Harvard in 1893, began a career in journalism, and joined the staff of his father’s New York Evening Post. Upon his father’s death in 1900, he became president and owner. Like his grandfather, he was a pacifist and was against the U.S. entry into World War I. Later, he was a member of the America First Committee, which opposed the U.S. entering World War II. He sold the Post in 1918 but retained control of its weekly edition The Nation, which he molded into a journal of social protest. He stepped down to the position of contributing editor in 1932 and sold the magazine in 1935.

Following a lynching and race-related violence in Illinois in 1908, philanthropist William English Walling visited the Springfield scene and was shocked not only by the carnage, but that such race-motivated violence could occur in the North. Demanding a response, he wrote about what he’d seen and reached out to other reformers, including Villard, Jane Addams, Lincoln Steffens and editor William Dean Howells. With others, Villard and his mother were founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909. For years he served as its treasurer.

Villard was the author of a number of books, including an autobiography Fighting Years. His oldest son Henry Hilgard Villard was head of the economics department at City College and the first male president of Planned Parenthood of New York City.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)