Chemist

Centurion, 1894–1955

Born 14 April 1866 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 29 April 1955 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Vanderbilt Family Cemetery and Mausoleum , New Dorp, New York

, New Dorp, New York

Proposed by Charles F. Chandler and J. Howard Van Amringe

Elected 7 April 1894 at age twenty-seven

Archivist’s Note: Son of William H. Schieffelin; grandson of John Jay; nephew of William Jay and Edmund R. Robinson; cousin of John Jay Chapman; son-in-law of Elliott F. Shepard; father of Bayard Schieffelin and William J. Schieffelin Jr.

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

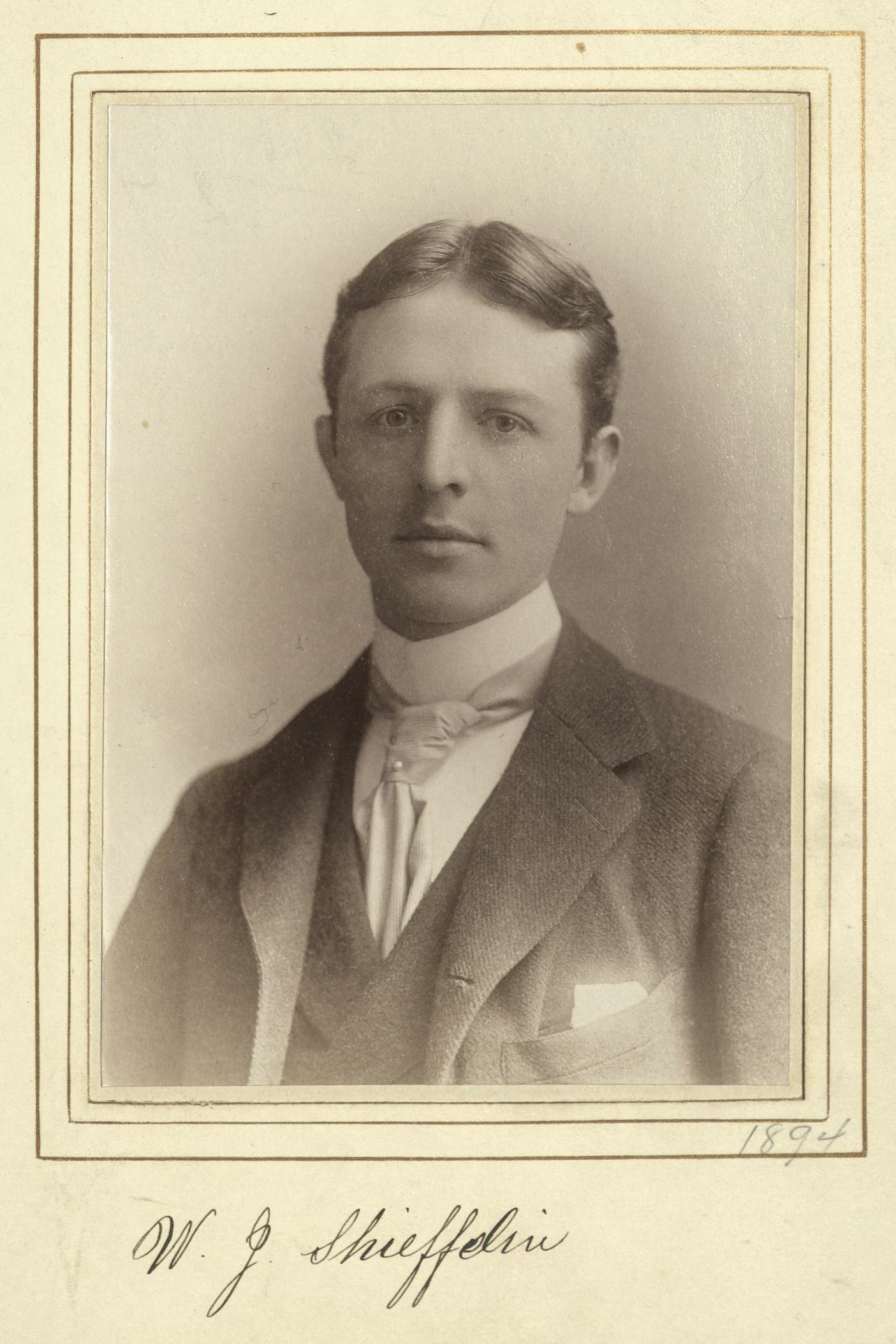

William Jay Schieffelin graduated from Columbia School of Mines in 1887, and then took a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of Munich. He always thought of himself as a chemist, and for many years he was head of the great pharmaceutical house of Schieffelin & Co., for which he had been destined.

An all-wise Providence, however, led him, while still very young, to associate himself with the Citizens’ Union, and he was the active president of it for thirty-two stormy years. This threw him into the City’s politics, and he entered the arena not to hold public office but to battle the powers of darkness with an enthusiasm and fervor that were the wonder and admiration of all good men. He was a consecrated crusader, and he never grew tired. Although Tammany Hall was almost always the target in the never-ending struggle, he steadfastly maintained that the Citizens’ Union was a non-partisan organization, and he pointed out that it had consistently supported Alfred E. Smith, James A. Farley, and other Democratic candidates who demonstrated high standards of competence and honesty.

Besides clean government Schieffelin’s other great interest was Negroes. He was a trustee of Hampton Institute, and he was always working for better conditions in the factories and homes where Negroes worked and lived. At the outbreak of the First World War he formally offered to raise a Negro cavalry regiment, of which he would be Colonel; but the offer was rejected by the President [Woodrow Wilson]. The Governor [Charles Seymour Whitman], however, appointed him Colonel of the 15th New York Infantry (a Negro regiment of the State Guard).

Schieffelin was elected to the Century when he was only twenty-eight years old [sic: twenty-seven]. He was young and gay, and good-looking, and he was full of confidence, and willingness to labor in the Lord’s vineyard. Everybody liked him, and wished him well, and supported the Citizens’ Union largely because they had confidence in his integrity. He was a person of great independence. Once at a trustees’ board, referring to the president, who was present, he said: “This is the first time in my forty years of service on this board that we have had a president who is neither a Christian nor a gentleman.”

The difficulty with such frankness is that it does not generally contribute to getting things done. And yet, sometimes it does. John Jay Chapman had a way of saying aloud whatever occurred to him, and his considered remarks exploded like dynamite. Perhaps it depends on the intellectual content. In the day of the salesman and the public relations expert it is well to remember that we really don’t like panders; and Schieffelin was always willing to say so.

He was a member of the Club for sixty-one years—a long, pleasant time except at the end when he was invalided, but even then he was so courageous and cheerful it was an example to all of us. He was not a profound thinker nor a scholar in any field, but he was a man of broad intelligence and deep public interest, and he gave his time and talents to defend the City from those who would prey on it. It is remarkable that he was so little plagued with the bickerings and derision that soldiers of the cross are heir to, and this must be accounted to his happy and generous disposition; for though he was self-confident and not always tactful, he was never rude by inadvertence, nor did he proceed by indirection. He was, indeed, a gallant Christian gentleman.

George W. Martin

1956 Century Association Yearbook