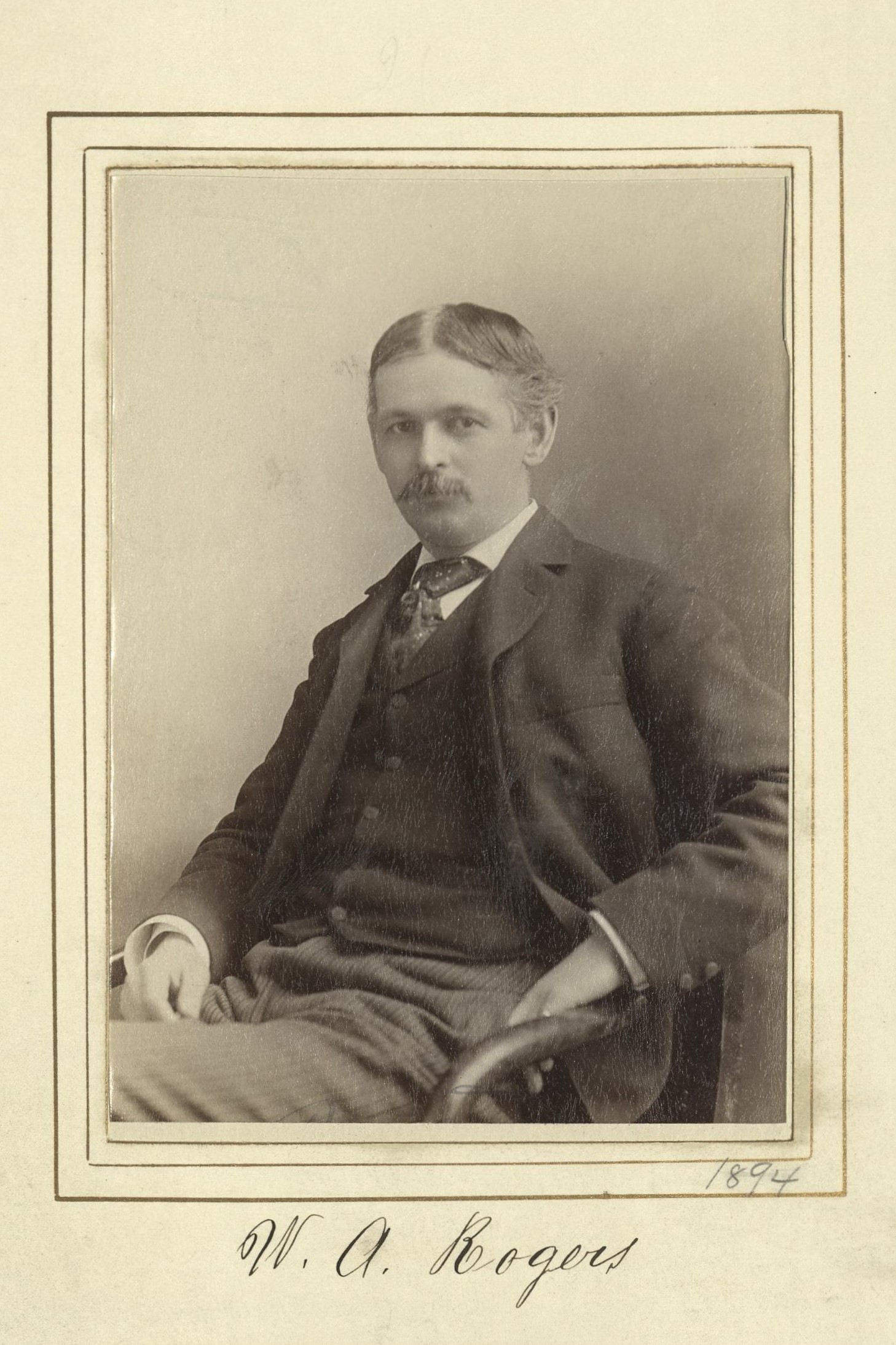

Artist/Political Cartoonist

Centurion, 1894–1931

Born 23 March 1854 in Springfield, Ohio

Died 20 October 1931 in Washington, District of Columbia

Buried Ferncliff Cemetery , Springfield, Ohio

, Springfield, Ohio

Proposed by Poultney Bigelow and Francis Davis Millet

Elected 7 April 1894 at age forty

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

In this country the political cartoonist has played a larger part than anywhere else in the world. Punch would possibly dispute the assertion, and it will readily be acknowledged that a few of the Punch cartoons, notably the celebrated “Dropping the Pilot” of 1890, made profound political impression. But the British cartoon is as a rule either merely amusing or else extremely obvious. It can seldom have aspired to reverse public opinion, which is precisely what the American political cartoonist at his best invariably undertakes to do. William Allen Rogers came in lineal succession to a list of cartoonists with whom American politicians had to reckon. The cartoons of Harper’s Weekly in the Seventies and of Puck in the Eighties had been distinctly part of the period’s political struggles, municipal contests and national campaigns. Rogers was a much better draftsman than Thomas Nast and a much more accomplished artist than Joseph Kepler, but it is doubtful if his drawings swayed public opinion equally with Nast’s cartoons in the attack on Tweed or with Kepler’s in the Blaine-Cleveland campaign. Political circumstances do not often make possible such achievements of a psychological moment as the famous “Who Stole the People’s Money?” of 1871 or the “Belshazzar’s Feast” of 1884; yet Rogers’ cartoons made their political impression. “The Old Game Renewed,” published in Harper’s Weekly while Bryan and “Coin Harvey” were in the political limelight during 1896, the “Willie in Wonderland,” drawn when that year’s rise in wheat before election day upset the doctrines of the Populists, were doubtless addressed to readers strongly in sympathy with the cartoonist’s view. They may not therefore have been vote-winners, and perhaps that was also true of Rogers’ vigorous drawings during the European war, which struck a deeper note. Yet they strengthened public convictions.

Like most of his fellow-craftsmen in that special field, Rogers had not planned his career beforehand. He was an illustrator with an unusually sure and vivid touch; his earlier ideal for his own achievement was the work of Edwin Abbey. But if he entertained regret for the diversion of his talents to a much more restricted purpose, there were compensations. Booth Tarkington, whose aspirations in the same direction met with emphatic discouragement from the publishers, wrote to Rogers that this was why “I was driven to my present laborious occupation, which hasn’t half the joy of yours.” So jealous a guardian of the traditions as John La Farge told Rogers that “this daily task of yours calls upon all of the artist’s powers—the imaginative faculty, the knowledge of fact and its expression, a special quality of line and composition—and of course a something unexplained which is perhaps the most important of all.”

Alexander Dana Noyes

1932 Century Association Yearbook