British Lord/Philanthropist

Centurion, 1858–1923

Born 26 April 1828 in Canterbury, Kent, England

Died 4 February 1923 in Washington, District of Columbia

Buried Oak Hill Cemetery , Washington, District of Columbia

, Washington, District of Columbia

Proposed by Egbert L. Vielé

Elected 6 March 1858 at age twenty-nine

Archivist’s Note: Brother-in-law of John Jay; uncle of William Jay

Century Memorial

In two of the four past presidential terms the Century Club was represented at the White House; the only living ex-presidents of the United States are now on its membership roll. It has often had a voice in the House of Representatives; it still has representation in the Senate; the present Premier of Canada [W. L. Mackenzie King] is of our fellowship. But for the Century to provide from its active membership for the personnel of the British House of Lords was a novel achievement.

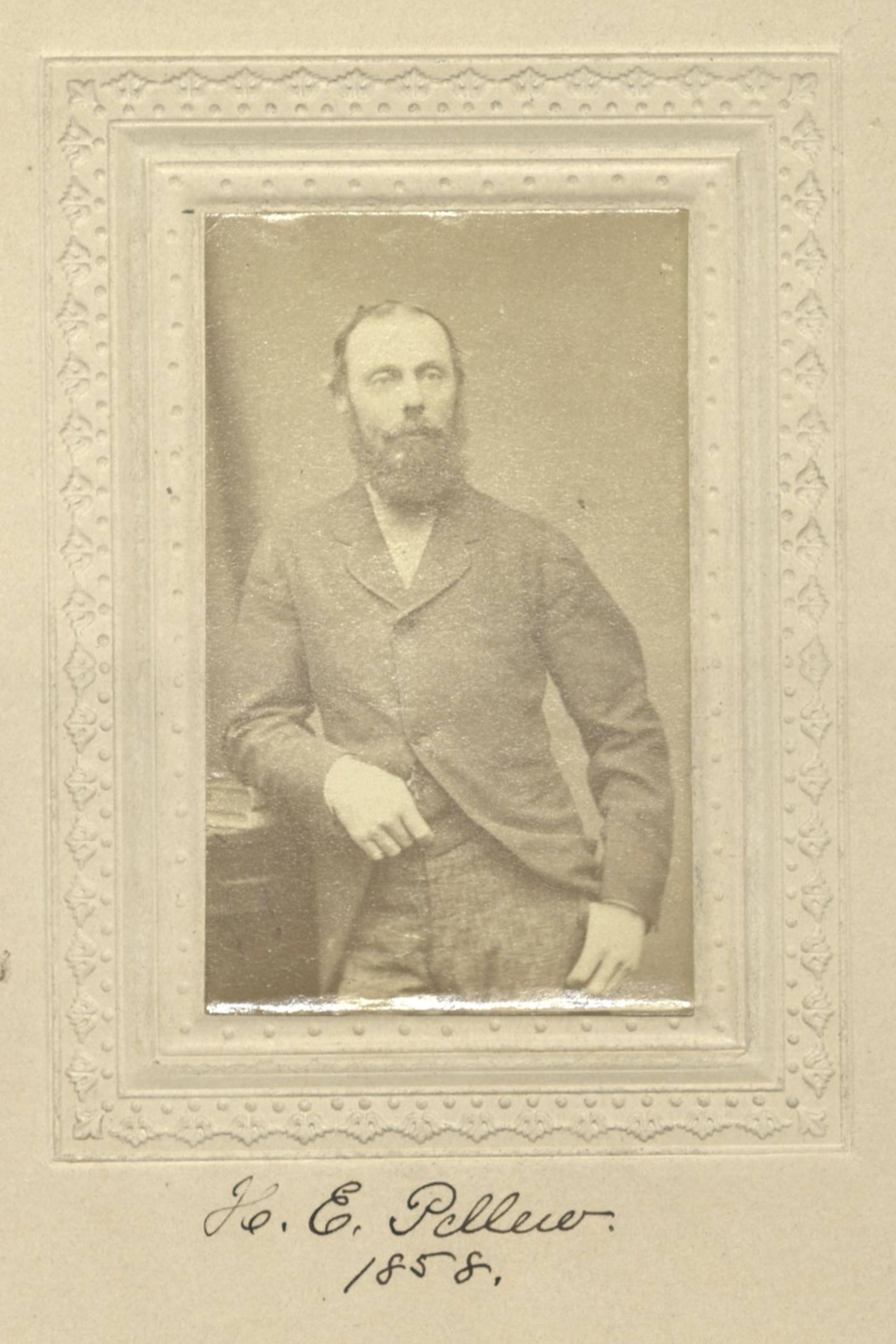

The American citizen on whom this distinction originally fell was the oldest member of the Club. Henry Edward Pellew was admitted to the Century in 1858; he was ninety-four years old when in August of 1922, on the death of the last male representative in the direct line of succession, he became by English law the sixth Viscount Exmouth. That he never formally assumed the title did not interfere with the Century’s representation in the House of Lords; his son and successor in the peerage is a seasoned New Yorker and Centurion.

Perhaps because of the great age of the elder Pellew, perhaps because of his thirty-five years’ residence at Washington, it is probable that few men in the Century recall his very real achievement as a philanthropist and civic reformer in New York and its remarkable background in his English affiliations. He was grandson on the paternal side to the celebrated British admiral who destroyed the Barbary pirates in 1816, on the maternal side to the British premier who succeeded William Pitt, and his hereditary British traditions blended oddly with his genuine Americanism. Only a year or two before his death, he expressed to his somewhat astonished son his resentment at the rector of his country church for reading the Declaration of Independence from the pulpit on July Fourth. It was not, the old gentleman explained, because he was anything but a loyal and patriotic American but because, on his boyhood visits to his grandfather at Richmond Park, that relative “used to show me the fenceposts which George the Third had set up with his own hands when he went there, and I can’t stand hearing a personal friend of the family called a tyrant and a despot.”

Pellew first came to America in 1848 after his graduation from Cambridge, where he had rowed stroke on the Varsity crew, using in published reports the inverted name “Wellep” for fear that his family would forbid such avocations. He visited our South and West of those early days; summing up his experiences in the remark, not often heard in this country at the time, that Dickens’s “Martin Chuzzlewit” did not begin to tell all that actually happened along the Mississippi. Between the early ’50’s and the early ’70’s Pellew lived alternately at London, where he was county magistrate and one of the founders of Keble College, and at New York, in which latter city he made his permanent residence during the fifteen years after 1873. During that decade and a half he was President of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, member of the Board of Education, helped to reorganize the Street Cleaning Department and was instrumental in constructing and running the first Model Tenement Buildings. In his Westchester country-place at Katonah, he is still remembered for his activities as President of the old Bedford Farmers’ Club; notably for his first introducing of thoroughbred Guernsey and Berkshire cattle into America.

Here was a strangely interesting international career; it might be called a fusion, both in personality and achievement, of the early Victorian type of English country gentleman and the civic reformer in American private life. If its incidents reflect a period which is now mostly a memory, it is a useful and salutary memory; whose link with the present was the deeply-rooted conviction of this old-time Centurion that wherever a man was and whoever he was, he must use whatever means lay in his power to help his fellowmen.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1924 Century Association Yearbook