Lawyer

Centurion, 1899–1925

Born 4 March 1854 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 27 November 1925 in Baltimore, Maryland

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Charles Scribner and John T. Agnew

Elected 6 May 1899 at age forty-five

Archivist’s Note: Nephew of Cornelius R. Agnew and John T. Agnew; brother of Stewart Paton and William Agnew Paton; uncle of Richard Townley Paton

Century Memorials

The death of Charles Dudley Warner brought sincere sorrow to his personal friends and to the wider public who knew him in the world of literature; for he was a genuine man of letters, foreordained as such from his early boyhood. He was a contributor to the best magazines as an undergraduate, and with few interruptions wrote to the delight of the public and to the approval of men of the highest literary taste up to the time of his death, long before which he had received that recognition and high reputation which he deserved.

Coming from the best New England stock, deprived of his father’s care when a mere child, his inherited intellectual qualities asserted themselves in the choice of a profession, rather than the business career which had been marked out for him, and he graduated at Hamilton College, studied law and was admitted to the bar, from which he was enticed by a happy chance to an association in 1860 with his classmate and lifelong friend, General, afterwards Senator, Hawley, in the editorship of The Hartford Courant, which he conducted with indefatigable energy, giving it the literary reputation it has always maintained, and he was still connected with it at the time of his death.

In 1884 he joined the staff of Harper’s Magazine and conducted the Editor’s Drawer and the Editor’s Study until 1898, besides contributing many articles to other departments of the magazine.

He was the author of many books, among which are the delightful collection of papers entitled “My Summer in a Garden,” “Being a Boy,” “The Golden House,” “Backlog Studies,” “Their Pilgrimage,” twenty-five in all, and in addition was the general editor of the American Men of Letters series and the managing editor of a Library of the World’s Best Literature, now publishing in thirty volumes, and collaborated with Samuel L. Clemens in “The Gilded Age,” and was at the time of his death engaged upon a novel.

With all this engrossing occupation he was throughout his life earnestly interested in all questions of social reform, lecturing before educational and other societies, active in the municipal and political life at his home in Hartford, serving on the State Commission on Prisons in Connecticut for a long time, and in the National Prison Association, studying the questions they involved for over thirty years, expounding them genially and persuasively, and seeing at last the methods of conducting convict prisons immensely advanced from the time when he began.

He was an earnest worker in all that he undertook. As a friend wrote of him, he “loved his friend and persuaded his enemy, and whoever touched but his finger drew after it his whole body.” He was as staunch after years of effort in a cause as new converts are wont to be, and never laid down that which he engaged in. His style was characterized by genial satire, quiet, delicious humor, caustic comment, charming simplicity, broad culture, and a ready assimilation of whatever was admirable in foreign life and letters. As Macaulay wrote of another, “wherever literature consoles sorrow or assuages pain, wherever it brings gladness to eyes which fail with wakefulness and tears, and ache for the dark house and the long sleep, there will he be remembered.” He was a most delightful companion for a fireside chat, with pipe and glass, even to the small hours of the morning, a genial, lovely soul, in many respects recalling the literary style of Irving, and, in other ways, that of Holmes. His philosophy is well expressed in a passage from his “Backlog Studies”:

“The longer I live, the more I am impressed with the excess of human kindness over human hatred, and the greater willingness to oblige than to disoblige, that one meets at every turn. The selfishness in politics, the jealousy in letters, the bickering in art, the bitterness in theology are all as nothing compared to the sweet charities, sacrifices and deferences of private life. The people are few whom to know intimately is to dislike. Of course you want to hate somebody, if you can, just to keep your powers of discrimination bright, and to save yourself from becoming a mere mush of good-nature; but perhaps it is well to hate some historical person who has been dead so long as to be indifferent to it. It is more comfortable to hate people we have never seen. I cannot but think that Judas Iscariot has been of great service to the world as a sort of buffer for moral indignation, which might have made a collision nearer home but for his utilized treachery.”

It was characteristic of him that he was on an errand of kindness, carrying books to a poor colored man who was fond of reading, when he was taken ill, and asked permission to rest for a few moments in a house by the way; and there, after a short time, he quietly and painlessly entered into the rest which is eternal.

Henry E. Howland

1901 Century Association Yearbook

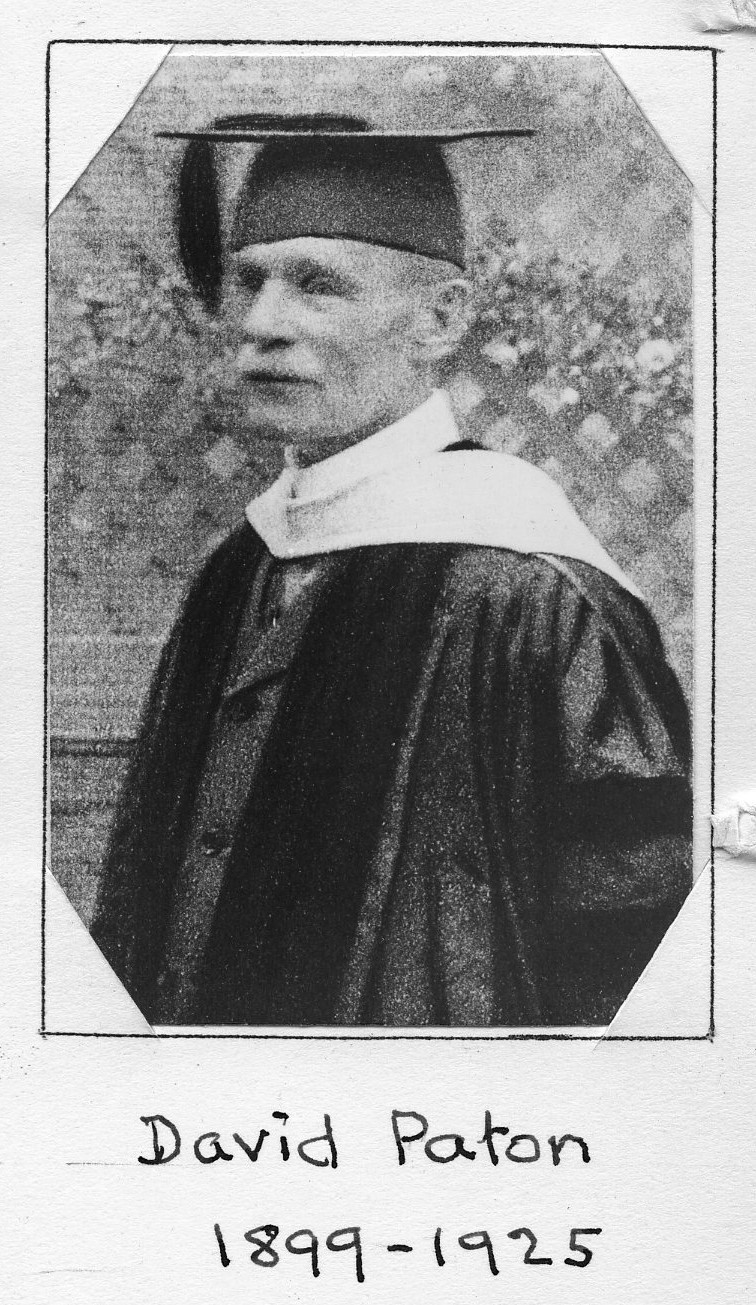

David Paton’s kindly and gentle life was bound up with Egyptian research, into the lore of which he had possibly penetrated deeper than any scholar of his time. During many years this fascinating and engrossing study had occupied all his time and energy; at the last, it is possible that Egypt of the Pharaohs was more real a community to him than the America of today. Almost a recluse in his labors at the Princeton University library, he yet kept touch with men of today, if not with things, and it was a notable gathering of friends and admirers who thronged to the University when he received the honorary degree of his Alma Mater.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1926 Century Association Yearbook