Lawyer

Centurion, 1891–1943

Born 3 September 1854 in New London, Connecticut

Died 24 December 1943 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Cedar Grove Cemetery , New London, Connecticut

, New London, Connecticut

Proposed by William H. Wisner and Henry Rogers

Elected 5 December 1891 at age thirty-seven

Century Memorial

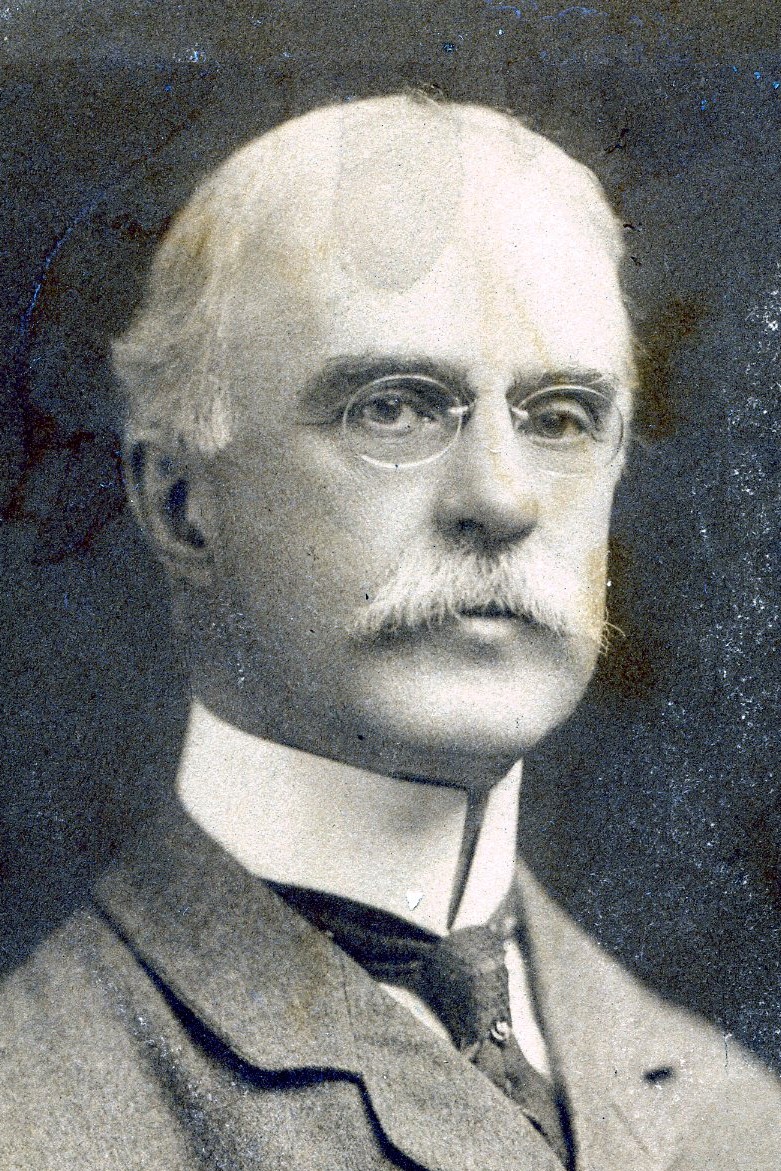

William Parkin, though one of our oldest Centurions, enjoyed the Club almost every day during the year prior to his death at almost ninety years of age. He had a fine record as a student at Yale, where he was valedictorian of the Class of 1874, and was a man of unusual mentality and culture. He remained to the end of his life a handsome figure with a mind of singular clarity that never became “weak by time and fate.” For about forty years he had been the Clerk of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and before that was a partner of W. W. Macfarland, one of the leaders of the New York bar. The appellate procedure of the Circuit Court of Appeals, which was created by Congress only a short time before he became its clerk, was largely the work of his hands, and because of the importance and variety of business of the Second Circuit had a far-reaching effect upon other courts. Parkin was not only a capable clerk of his court, but was also a favorite choice of the United States District Court for special master in complex and difficult accountings. His life and work in connection with the Court of Appeals furnishes a strong argument for maintaining a civil service at the high level of intelligence and character which for many years have been characteristic of the British system. Justice Frankfurter of the Supreme Court said in a recent letter about Parkin:

“One of the most disturbing things to me is the disesteem in which public service is held by us. And it is held in that disesteem because leaders of public opinion decry men who give their fives to undramatic service to the country instead of pursuing what are regarded as the more conventional ways of success. . . . One cannot expect a society to be founded on heroes and saints. These are always sports. And I just wonder how we shall ever be able to tackle the increasing complexities of our society without inculcating that respect for quiet, unostentatious and indispensable work like Parkin’s in which the British hold their Civil Service.”

Parkin’s kindly helpfulness and uniform courtesy rendered his administration of his office most satisfactory to the judges and always gratifying to the bar. Had it not been for his extreme reticence he would have achieved what is generally considered a greater measure of success. He deserves special remembrance because he did not seek that kind of success but was content to keep the noiseless tenor of his way even though he gained but slight personal recognition in view of his substantial abilities. He was one of those numerous public servants who are indispensable because it is they who really keep the government machinery running. He led a useful though very quiet life, and one that seems to have been not only serene but fortunate. At least he wrote the Secretary of his Class at Yale: “My life has been uneventful, and as it has no history should be called a happy one.”

Geoffrey Parsons

1943 Century Memorials