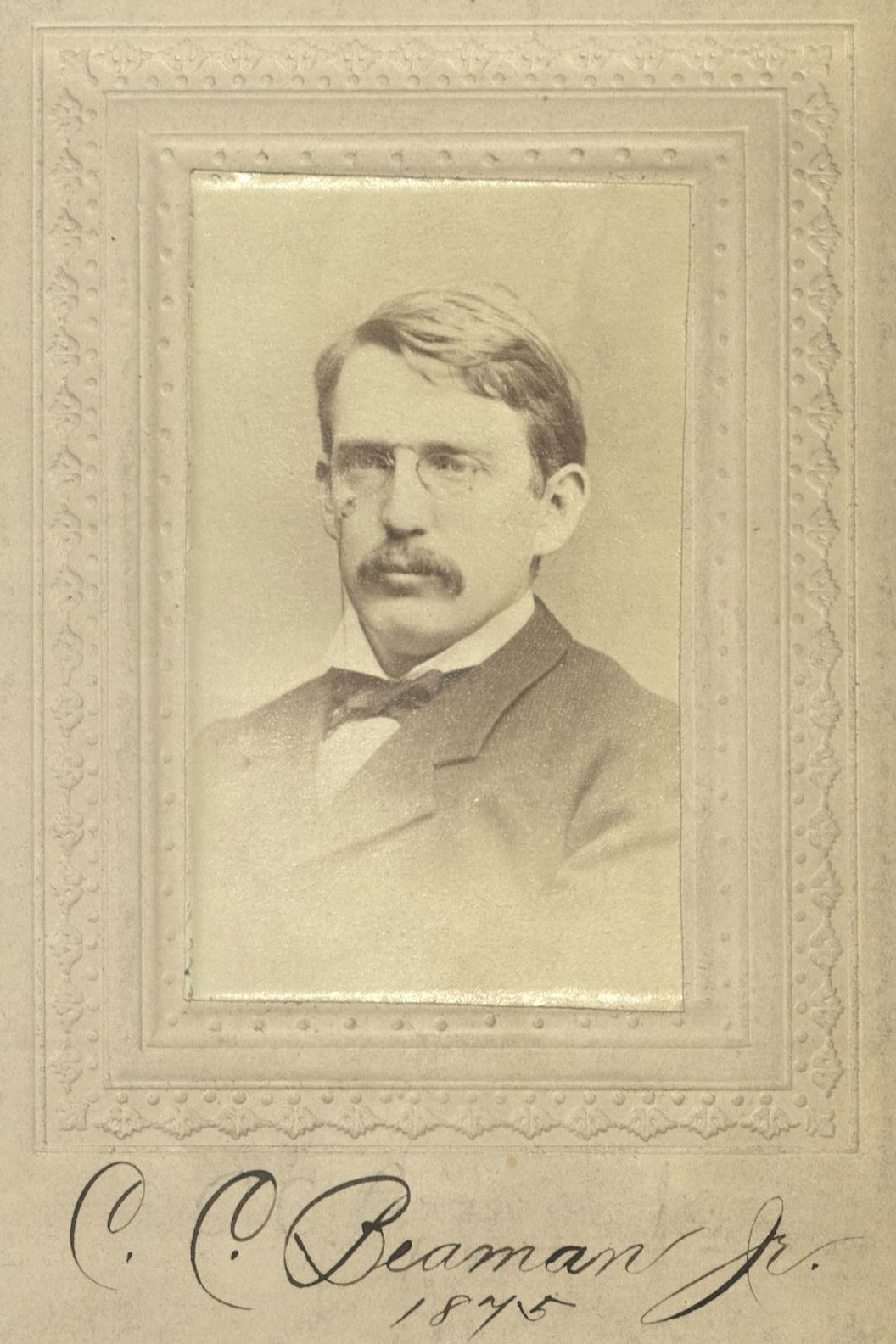

Lawyer/Public Servant

Centurion, 1875–1900

Born 7 May 1840 in Houlton, Maine

Died 15 December 1900 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Ascutney Cemetery , Windsor, Vermont

, Windsor, Vermont

Proposed by William M. Evarts and Thomas Hicks

Elected 4 December 1875 at age thirty-five

Archivist’s Note: Son-in-law of William M. Evarts; brother-in-law of Allen W. Evarts and Prescott Evarts; uncle of William M. Evarts, Edward Newton Perkins, Maxwell Evarts Perkins, and Harrison Tweed; father-in-law of Herbert C. Lakin

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

Nature casts men in various forms, but rarely does she give to the world a more thoroughly finished product than Charles C. Beaman, for there were combined in him all those qualities that command the respect and win the love of men—strength and gentleness, marked ability, a high sense of duty, kindly thoughtfulness for others, geniality of temper, brilliant wit, and unfailing generosity. With these, his only inheritance from his parents—for his father was a New England country clergyman dependent upon a moderate salary for his support, and in whose home the pinch of poverty was only averted by the strictest economy—he won his way to distinction in a community where there is no royal road to success, and where rivalry is fierce and unceasing. The incidents in his career are like a finished romance. It is a story which every father can place before his boys and ask no better of them than to copy it. New England has furnished many a parallel in its early features.

It is said that genius consists in seizing upon opportunity, and his career justifies the assertion.

After graduating at Harvard in 1861, where he made a marked impression, and an interval of school teaching to furnish the means of livelihood, he entered the Harvard Law School, and in 1865 was awarded the first prize for his essay on the “Rights and duties of belligerent war vessels.” It was well written, displaying discriminating judgment and an admirable knowledge of international law, and when published in the North American Review attracted the attention of Senator Sumner, who was about to make an important speech in the Senate upon the claims against England for the ravages of the Alabama. He appointed Beaman his secretary and clerk of the Committee on Foreign Relations in the Senate.

In 1868 he began to practise in New York, and published his book on the “Alabama claims and their settlement” in 1871. He was at this time appointed examiner of claims in the Department of State, an office which he filled with signal ability.

He was appointed by the President solicitor of the United States before the Tribunal of Arbitration at Geneva, a selection which was due to the knowledge of the subject which he had displayed, and to the influential gentlemen connected with the Commission who realized his ability. At Paris he soon showed that he knew more about the details of the claims than anyone else, and was in constant consultation with Messrs. Cushing, Evarts and Waite, the counsel for the United States. Mr. Evarts was accompanied by his family, and Beaman there made the acquaintance of his daughter, Miss Hettie Sherman Evarts, whom he subsequently married.

After the conclusion of the arbitration and the payment of the award by Great Britain, he represented many of the claimants in establishing their claims, and of course received substantial reward for his services. His opportunity came by the chance choice of a subject for a prize thesis, and he so well availed himself of it that it brought him position, his wife, and a fortune.

Since that time he has practised his profession in this city for several years in partnership with Edward N. Dickerson, a distinguished patent lawyer, and since 1879 as a member of that firm of notable lawyers, composed of such leaders of the bar as William M. Evarts, Charles F. Southmayd and Joseph H. Choate. By the retirement of its senior members he was at the time of his death practically at its head; as such, entrusted with the largest and most important business interests as counsel for great railway lines, for important corporations and leading capitalists, whose financial operations were world-wide. How well he administered these weighty trusts all who were brought in contact with him will freely admit.

His trained legal mind, sound judgment, far-reaching sagacity, fair conclusions and conciliatory spirit were effective and convincing, brought him high reputation and successful issues to his clients. With all this engrossing professional work pressing upon him, he was always a leader in any movement for the public good, social, charitable or political, unsparing in his efforts and regardless of himself.

He was chairman of the Conference Committee of Seventy in the reform movement of 1894, prominent in the Municipal Campaign of 1897, and during the last months of his life earnest and devoted in the work of the Charter Revision Commission, which taxed his energies severely and sapped his strength. For all this service he refused honors and reward, save that which he valued most of all, the approbation and respect of his friends and the public.

But it was for his personal qualities that he will be best remembered. He was the cheeriest man that ever drew the breath of life, bubbling over with boyish enthusiasm, gifted with an irrepressible humor,

“Whose wit in the combat as gentle as bright,

Ne’er carried a heart-stain away on its blade.”

Buoyant, fascinating, pervading the very air with his contagious sympathy, he was the centre of every social gathering and the best man at a dinner table for raillery, repartee and brilliant passage at arms in conversation this generation has ever known.

“He made a July day short as December,

And with his varying childness cured in us

Thoughts that would thick our blood.”

He was responsive in his sympathy with suffering and sorrow, quick in his emotions, gracious in his universal benevolence, gentle and tender with every young thing, and the very soul of hospitality, which, as hundreds of his friends will long remember, he dispensed with a lavish hand at his estate of “Blow-me-down,” which he loved so well, at Cornish, New Hampshire. He was a grateful, affectionate and careful son, a loving husband, a devoted, thoughtful father, a kind and helpful neighbor, and a noble man. It seems impossible to think o[f] him as dead. No man could have left a larger gap, for he brightened his world while in it and it is poorer for his going. He died as he had lived, like a Christian gentleman, knowing that his end was near, in the full possession of his faculties, with a message on his lips (to use his own words): “Give my love to all my friends. I don’t think I have many enemies”; in which every one who knew him will concur.

Although the summons came to him in his prime, the measure of his life was as full as if it had rounded out the Psalmist’s term of human existence up to the limit beyond which all is vanity, and he came to his eternal rest as one who

“Bends to the grave with unperceiv’d decay,

While resignation gently slopes the way;

And, all his prospects brightening to the last,

His heaven commences ere the world be past.”

Henry E. Howland

1901 Century Association Yearbook