Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

George McAneny

Secretary/Manhattan Borough President

Centurion, 1899–1953

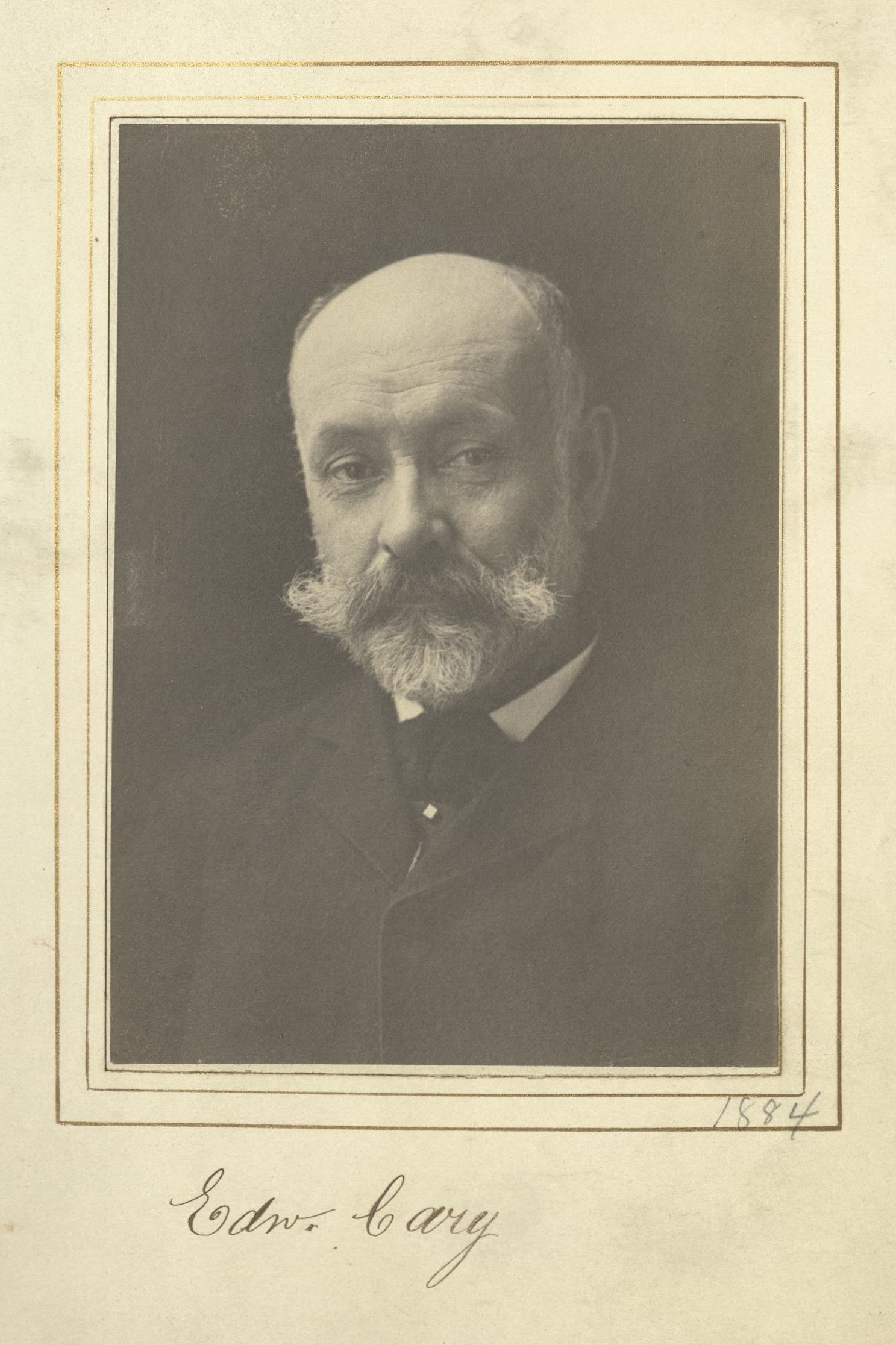

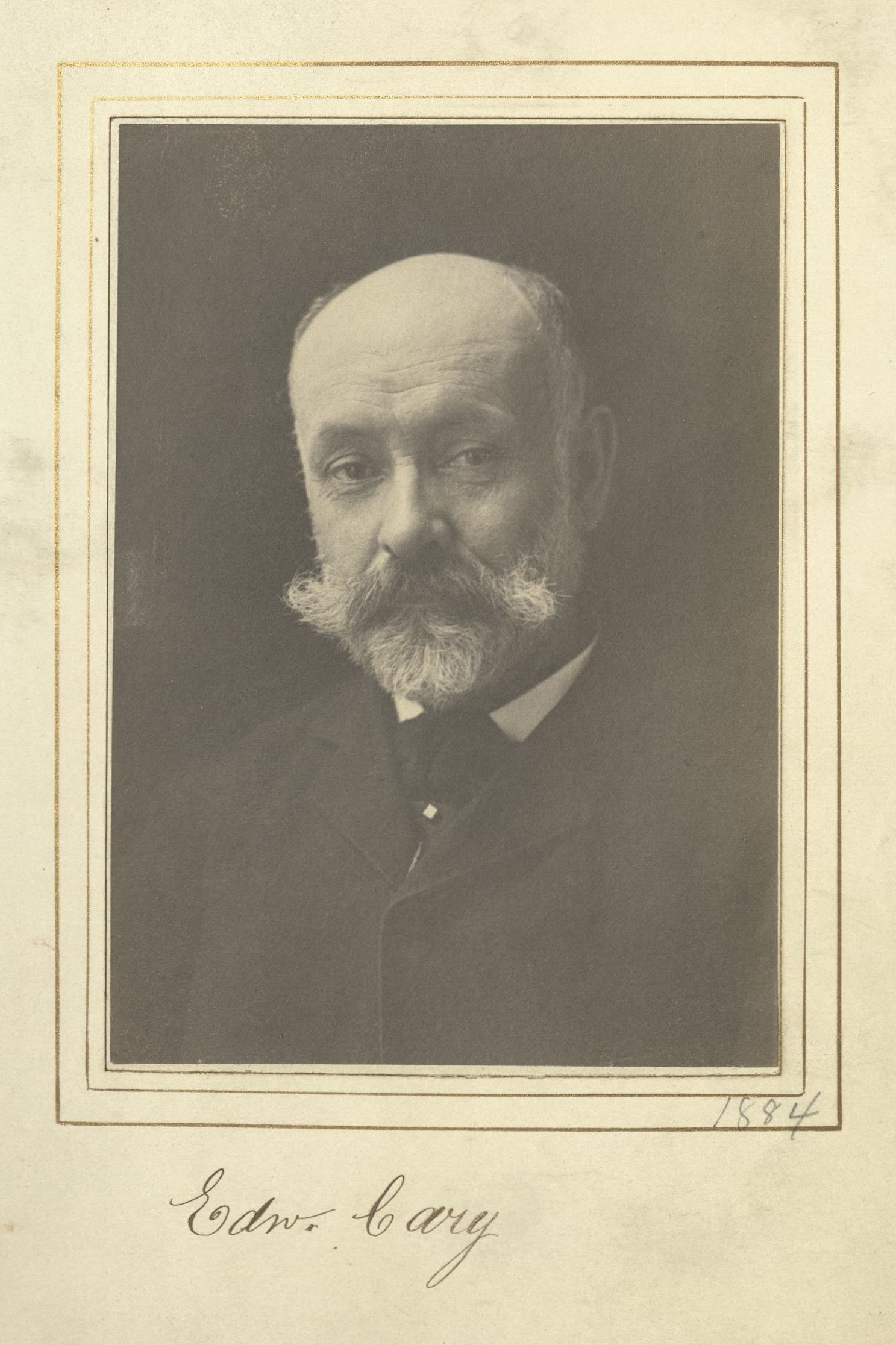

Edward Cary and Carl Schurz

Greenville, New Jersey

Princeton, New Jersey

Age twenty-nine

Century Memorial

It is quite impossible in this short space to give an adequate account of George McAneny. He referred to himself as a banker and a publicist, but he did not in the least fulfil the popular idea of these callings. He was the most useful servant of the City of New York of his time. Every little while he was compelled by necessity to earn some money, and then he worked for banks or newspapers; but his heart was always with the great City, which he loved, and toiled for, and lived in.

When he was very young, he had the good fortune to be closely associated with Carl Schurz and Edward M. Shepard. These were the giants of those days, and they were earnestly and effectively concerned with Civil Service reform. Before he was twenty-one, McAneny was inculcated with the importance of this problem, and his interest never flagged. Tirelessly, relentlessly, he pursued the politicians who lived off the traffic in appointments, and he was the principal author and advocate of the state Civil Service Law.

From Civil Service he went on to organize the whole course of Fusion—when that word stood for a significant and powerful force in City government. He became President of the Borough of Manhattan, President of the Board of Aldermen, and Controller of the City at a time when financial disaster seemed inevitable, and, but for him, would have come to pass. He seemed to have some magic in dealing with the curious specimens who were incumbents of the office of Mayor previous to La Guardia. They sometimes listened to him when they would listen to no one else.

To the preservation of what is old and distinguished in the City’s architectural past he brought his native shrewdness, and he worked on the planning of the City for the future with an inspired vision of the possibilities of things. To plan a city is no job for a closet theorist. Zoning and subways and setbacks are fought by vested interests with every weapon in the armory of politicians and property owners, and animosities are engendered that endure long after the battles are lost and won.

How was it that McAneny survived these years of turmoil, and emerged with the affectionate respect and admiration of his fellows from a field where so many good men and true have retired disillusioned and disgusted? It is certainly by reason of what he was quite as much as because of what he did. For he was a completely and disconcertingly honest man. What he thought, he said without subterfuge or indirection. Men entrusted him with money and with office in a confidence that was never violated.

He knew the City government like the palm of his hand. He knew where the bad spots were and where the strength lay. He conceived of it as a great social agency to be administered for the benefit of them that lived therein. And to the fulfilment of this conception he devoted his whole life. His confidence and enthusiasm acted like an elixir that made the fainthearted brave and the defeatists ashamed. This was more than mere urgency in discourse: it was a kind of divinity that shone from him and shaped the ends of effort far beyond the vision of ordinary men.

It isn’t enough to be honest and unafraid. It isn’t enough to be diligent and just. McAneny was also successful. When he entered the lists, the trumpet sounded and men flocked to his standard. Possunt quia posse videntur. Everything became possible!

It seems incredible that this gentle, soft-voiced man could have defeated again and again the powerful interests which ranged themselves in opposition. He was invulnerable to the ordinary slings and arrows that bring men down. His life was an open book, and his motives were unquestionable. He knew when men were telling the truth, and when they were lying; but he took it all without raising his voice—as though it were the weather.

He had a sweet and sensitive nature. He lived a long time, and his old friends got away before him. But to the end he reaped late harvests and received grateful tributes. After he was seventy-five, he saved the Brandywine Battlefield and the field of the battle of Princeton as memorial parks; he preserved the Old Philadelphia Custom House and defeated the proposal to obliterate Castle Clinton in the Battery. In recognition of these services he received, in his eighty-fourth year, the Conservation Service Award of the Department of the Interior, and he was as pleased and touched as only an old man can be.

Goodbye, Brother McAneny. We shall not see you any more on the back porch in the summertime, but we shall think of you with affection and remember you with gladness.

George W. Martin

1954 Century Association Yearbook

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

Edward CaryJournalistCenturion, 1884–1917

Edward CaryJournalistCenturion, 1884–1917 -

Raymond Blaine FosdickSociologist/WriterCenturion, 1921–1972

Raymond Blaine FosdickSociologist/WriterCenturion, 1921–1972 -

Elliot H. GoodwinSecretary, Civil Service Reform AssociationCenturion, 1911–1931

Elliot H. GoodwinSecretary, Civil Service Reform AssociationCenturion, 1911–1931 -

Carl SchurzStatesmanCenturion, 1892–1906

Carl SchurzStatesmanCenturion, 1892–1906 -

Carl L. SchurzLawyerCenturion, 1912–1924

Carl L. SchurzLawyerCenturion, 1912–1924 -

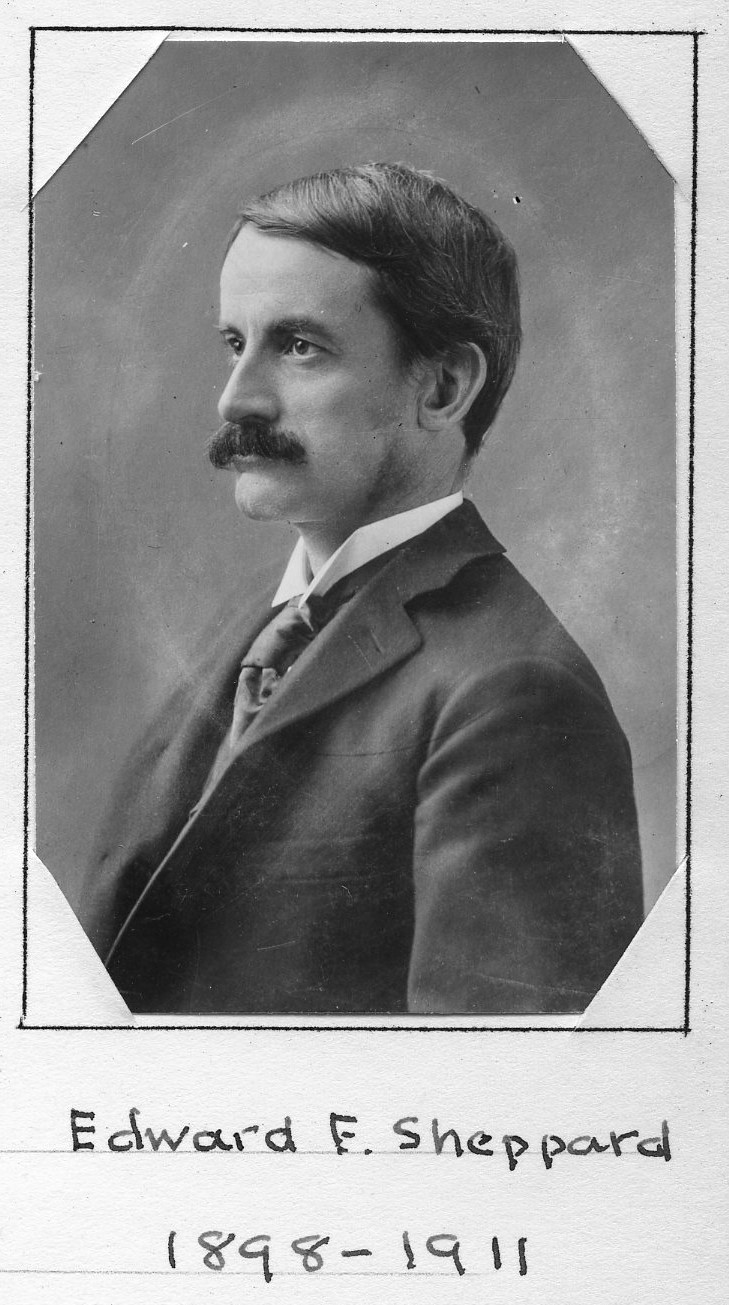

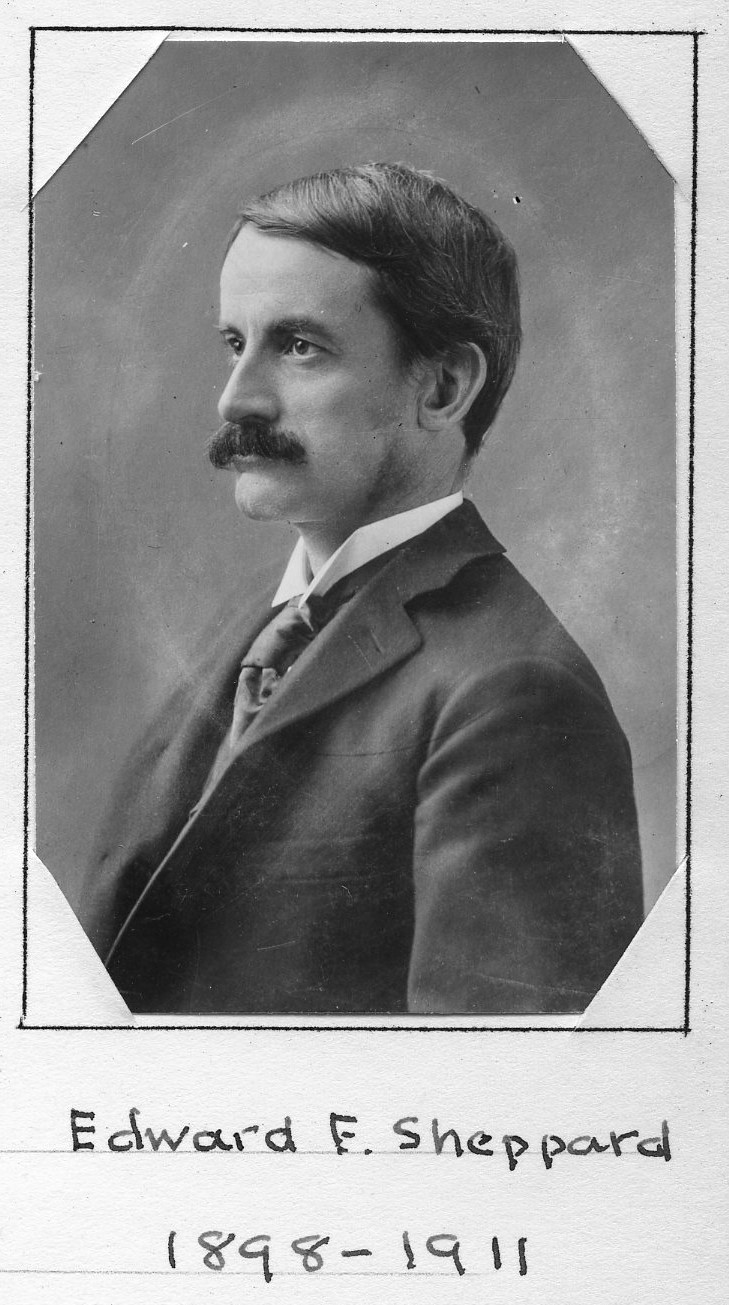

Edward M. ShepardLawyerCenturion, 1898–1911

Edward M. ShepardLawyerCenturion, 1898–1911 -

Timothy Shaler WilliamsRailway PresidentCenturion, 1922–1930

Timothy Shaler WilliamsRailway PresidentCenturion, 1922–1930