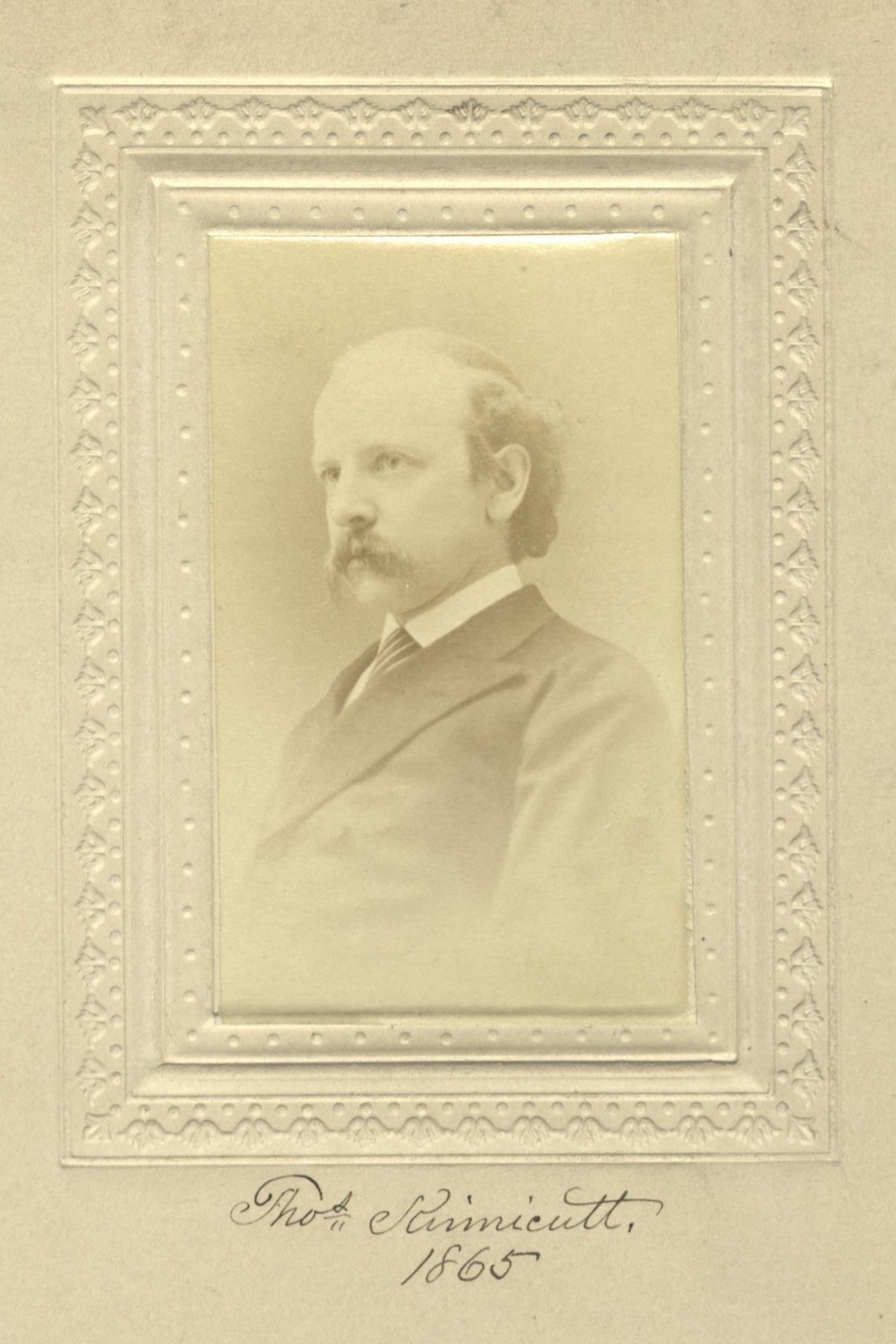

Merchant (Tobacco)/Lawyer

Centurion, 1865–1882

Born 13 July 1835 in Worcester, Massachusetts

Died 21 January 1882 in Worcester, Massachusetts

Buried Worcester Rural Cemetery , Worcester, Massachusetts

, Worcester, Massachusetts

Proposed by William H. Draper

Elected 4 November 1865 at age thirty

Archivist’s Note: Cousin of Francis P. Kinnicutt and Lincoln N. Kinnicutt

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

Thomas Kinnicutt hailed from a distinguished Worcester, Massachusetts, family. His father, Judge Thomas Kinnicutt, was a Whig representative to the General Court for several terms, speaker of the state house of representatives, state senator, selectman, and finally judge of probate for Worcester County. It was said that “he was a man of winning presence, and his manners had that sweet attractive kind of grace which was characteristic of the best specimens of the gentlemen of the old school,” but alas, “his physical powers were never of the strongest.”

The judge and his wife, Harriet Burling, originally from Natchez, Mississippi, had three children: a son, Thomas, who died age five; a daughter, Harriet; and finally our future Centurion, also named Thomas. Thomas’s mother died when he was three years of age, and his father remarried.

Thomas was a frail child and at age sixteen became partially deaf. Friends recalled “his sunny, affectionate temper, and disposition, an unselfish companion, a playmate always thoughtful of his associates, and looking out for himself last of all.” Attending Harvard College, he was a member of many societies, including the Fly Club, the Institute of 1770, Alpha Delta Phi, and the A.D. Club. He was also a member of the Rumford Society, whose aim was to improve the knowledge and practice of chemistry and natural philosophy. Students of scientific tastes of all classes were eligible for election. There was a laboratory and apparatus available for member use to conduct experiments. Admissions Committee rules stated: “two black balls were sufficient to reject a proposed member.” Perhaps this is where the Century Admissions Committee’s rules originated.

At graduation in 1856, Thomas was elected a member of the Class Committee and gave a dissertation on “The English Aristocracy.”

Thomas then embarked on his Grand Tour, a yearlong voyage to Calcutta, Egypt, and the Continent. After a brief legal internship, he entered Harvard Law School, where he won second prize for a legal essay “on a difficult and abstruse topic.” Graduating in 1860, he returned to Worcester (his father having died at age fifty-eight while Thomas was at law school) and entered into the practice of law at Devens, Hoar, and Hill, managed by Charles Devens, a former Whig member of the Massachusetts General Court and friend of Thomas’s late father.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Devens secured for himself a commission as colonel of the 15th Massachusetts Volunteers, made up of men from Worcester. In February 1862, Thomas proceeded to secure, he thought, a commission as a lieutenant in the same unit. He bought a uniform and reported to Colonel Devens in Poolesville, Maryland, where Colonel Devens informed him that all officer positions were already filled. (Perhaps the colonel felt that the less-than-robust, partially deaf Kinnicutt was too great a risk.) The 15th Massachusetts proceeded without Thomas to fight the Peninsular Campaign, the Maryland Campaign, including Antietam, and other major battles. The unit sustained the tenth highest casualties of any Federal unit in the war. Devens later became attorney general under President Rutherfurd B. Hayes.

“I returned to Worcester and have not since sought military glory,” Thomas later said. His infirmities grew on him, a friend later said, to the extent that he was unable to pursue a career in the law or public service, and he became secretary of the Bay State Fire Insurance Company. The insurance life didn’t suit him. Thomas contacted his old Harvard classmate, George Osgood Holyoke, who was in the tobacco business, and, in 1864 in a massive career change, moved to New York and joined Holyoke & Rogers on Water Street as a tobacco merchant. He later opened his own firm on Broad Street. There is scant information extant about his career, only one mention that he was a judge at the National Tobacco Fair in Louisville in 1866.

And he took his dog to work. An advertisement he placed in the New York Daily Herald on September 17, 1875, offered a “$20 reward for the return of a Black and Tan Terrier Slut [‘slut’ meaning female dog] weighing about 3 pounds, strayed or stolen from 52 Broad Street [Thomas’s office].”

As his health further declined, Thomas moved in with a first cousin, Dr. Francis P. Kinnicutt, and his wife at 4 East 37th Street. Dr. Kinnicutt, professor of medicine at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital, and a Centurion, was the physician of choice for the carriage trade, attending to, among others, the manic-depressive Teddy Wharton, husband of Edith. Edith asked Dr. Kinnicutt’s advice about what “soporific or nerve-calming drug” Lily Bart should take at the end of House of Mirth. A Kinnicutt descendant recounted that the Kinnicutts had “appalling taste—the house full of polar bears rugs, moose heads and antlers.” Mrs. Kinnicutt was “a woman of distinct character and frozen expression,” said the descendant, “all bust, bustles and severity. Her principal charitable work was placing NO SPITTING signs in the subways.”

While in New York, Thomas joined the Century in 1865 at age thirty (proposed by William H. Draper, a physician). He also in that year founded the Harvard Club with four other fellow Harvard graduates, and where he served on the Executive and Admissions Committees.

Dr. Kinnicutt was unable to prevent the onset of consumption in his cousin, and in 1879 Thomas departed the overstuffed house in the city (hopefully with his dog) for the highlands of Princeton, Massachusetts, outside of Worcester, returning in 1881 to Worcester and dying at the home of his uncle on January 21, 1882, at age forty-six. Neither Thomas nor his sister married.

It was said at his funeral, “In the homes of the more cultivated and refined people of the city, in the select associations of the Century and Harvard Clubs, at the social board where Learning and Refinement sat, he had his recognized and frequent place. His college song, his story of quaint and significant humor, were requisite to the completeness of many an entertainment.”

Alexander Sanger

2019 Century Association Yearbook