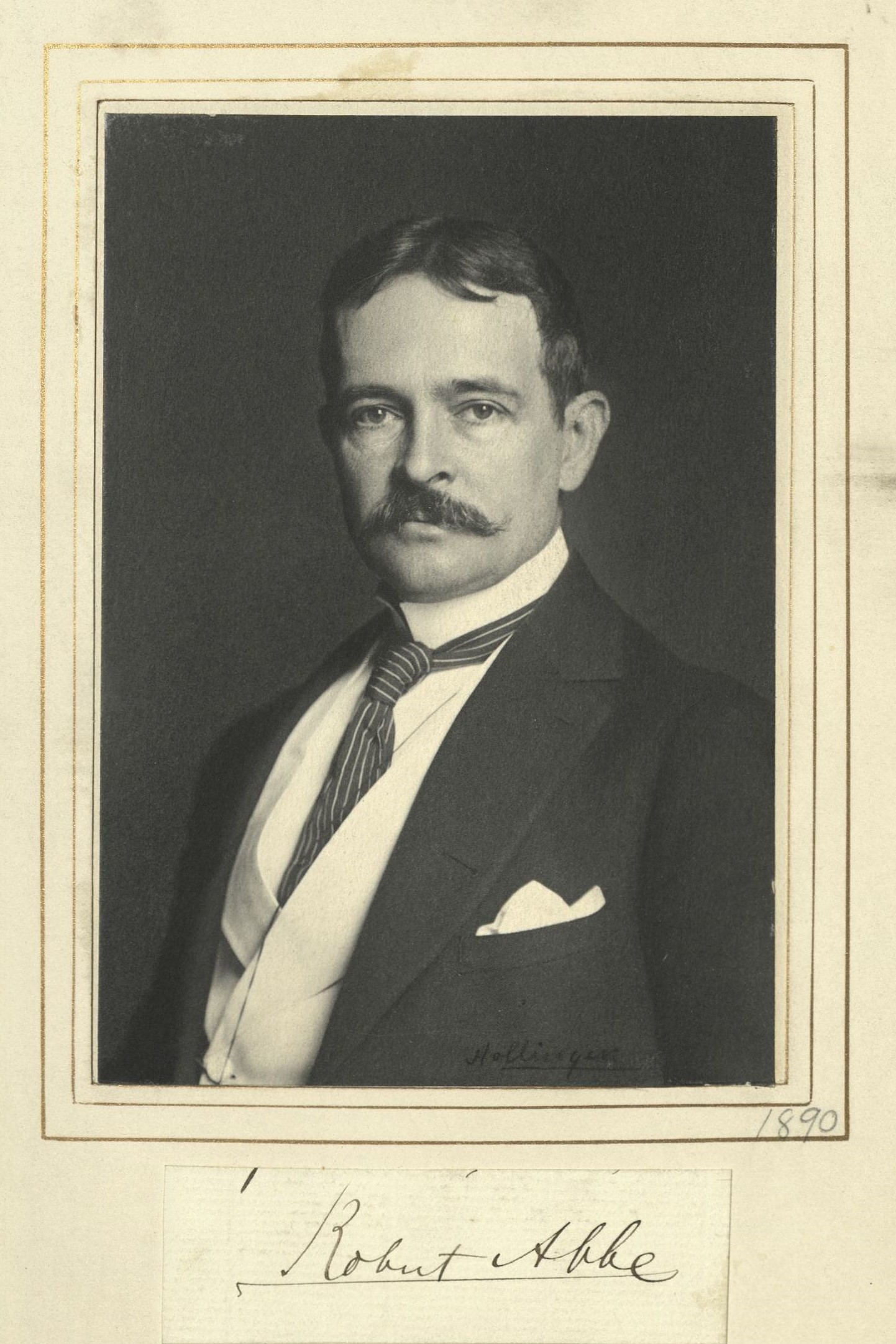

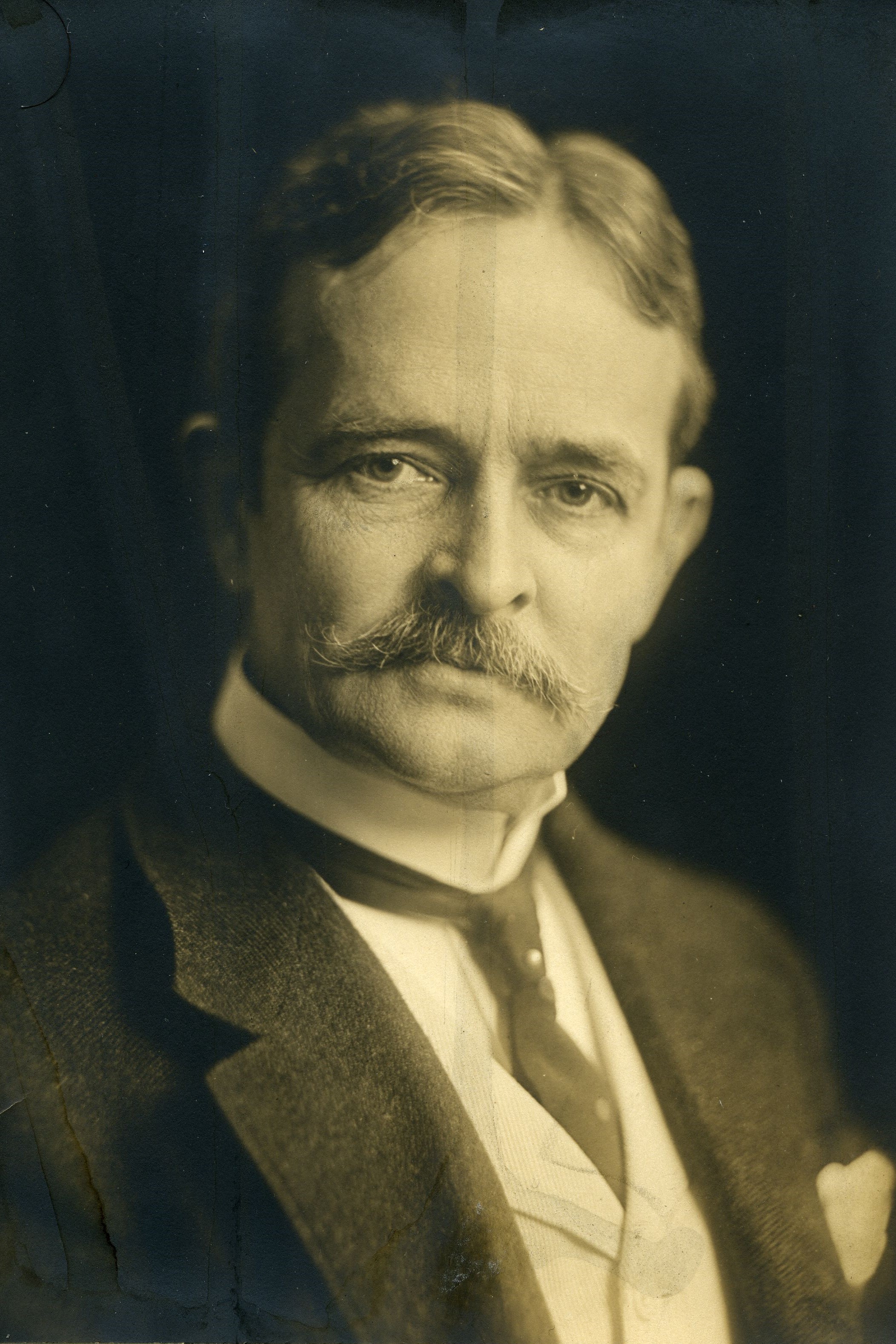

Surgeon/Radiologist

Centurion, 1890–1928

Born 13 April 1851 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 7 March 1928 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Woodlawn Cemetery , Bronx, New York

, Bronx, New York

Proposed by Robert F. Weir and George A. Peters

Elected 1 March 1890 at age thirty-eight

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

It would not be easy to say whether the larger mark which Robert Abbe made upon his time resulted from his extraordinary professional skill and imagination or from his personality. In the battle against disease, he stood in the first rank of pioneers. He was one of the men to whom we owe the present-day prolongation of active life, which makes us read with puzzled incredulity of Washington’s remark at the age of fifty-six, when asked to accept the Presidency, that he had hoped to spend in calm retirement the evening of life at which he had arrived, or Lincoln’s reminder to his neighbors, when leaving for the national capital at the age of fifty-two, that in Springfield he “had passed from a young to an old man.” Abbe had led the fight on cancer. The radium treatment was his special study in the laboratory, in the operating room, and in conference with the great French investigators. His own surgical operations were said to have numbered in the thousands, yet he was one of the first of our great surgeons to oppose the trend of a generation ago and make his own first objective the cure of so-called “surgical diseases” without the knife. In this day of specialization, he refused consistently to class himself as specialist. In surgery itself he was a master; as an eminent fellow-practitioner described him, he was equally an artist in all forms of manipulative skill, a good painter and a moulder of fine sculptural work.

The charm of Dr. Abbe’s character is less easy to describe; the secret of such personalities is elusive. Decision, courage and firmness were certainly not less impressive in him than the traits of kindly human tenderness. He met on even terms his fellow-scientists and men of action, but the hospital attendants told of the smiling line of faces when he entered the children’s ward, where the surgeon’s arrival was commonly a sign for panic. His Bar Harbor neighbors recalled that Abbe invariably had something worth while to give, in word or act, to every one with whom he came in contact. He expressed his sympathy with Pasteur’s “contempt for the philosopher who sat at his desk evolving theories, when in the laboratory truth might be found from facts,” but he quoted with even more cordial appreciation Pasteur’s retort to the Emperor Napoleon III, who had wondered with his bourgeois condescension why so eminent a practitioner was not rich, that the true scientist considered it beneath him to convert his knowledge into wealth. Life itself was a joy to Abbe; yet he wrote to a friend that “the pleasures of life are all in the way you look at them.” Success, he thought, “is due to persistent hard work and taking advantage of every opportunity.” Achievement, as he saw it, is like the climbing of Fujiyama; “the nearer one gets to the top the harder it seems, then all of a sudden one is there.”

Alexander Dana Noyes

1929 Century Association Yearbook