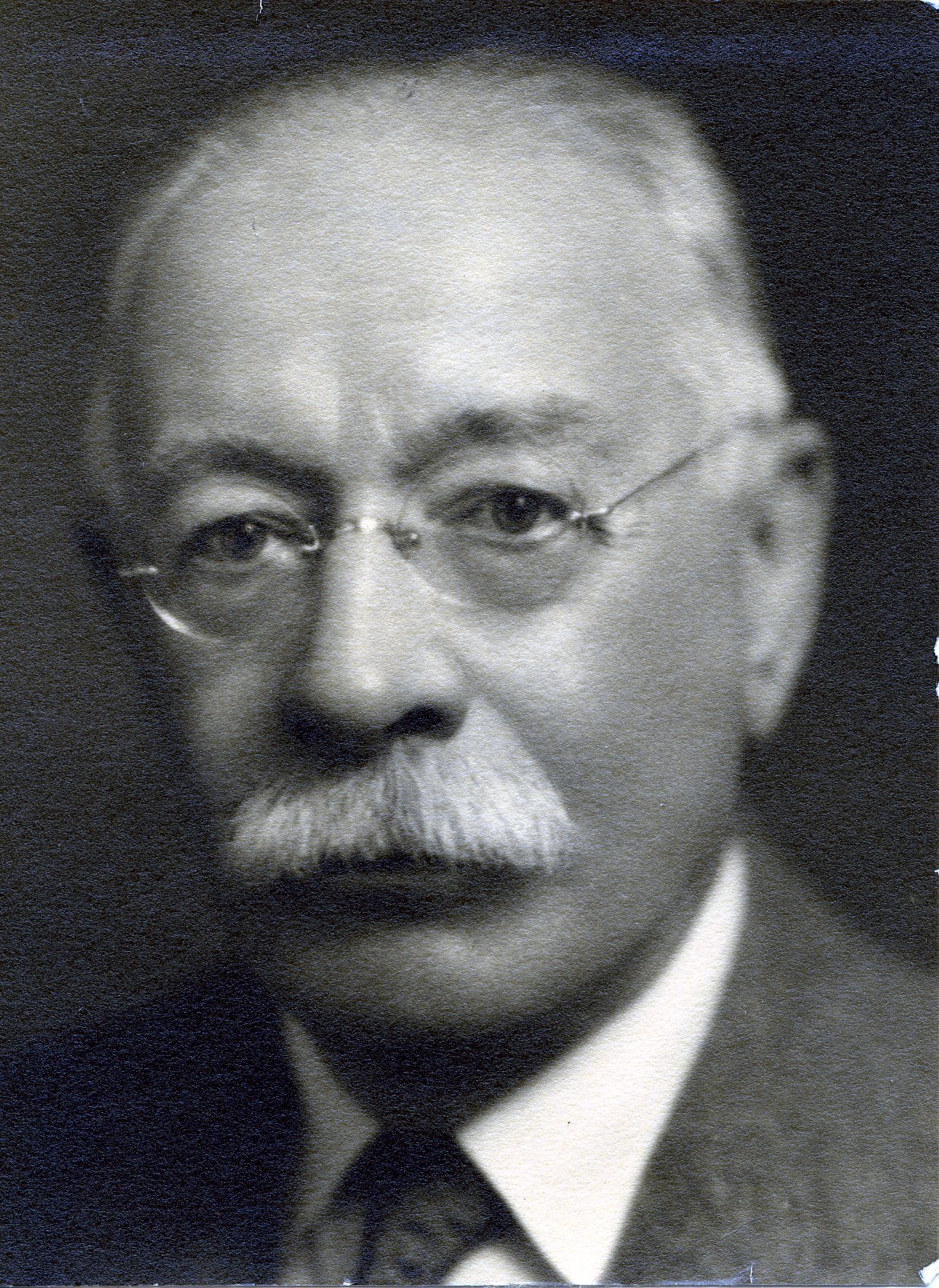

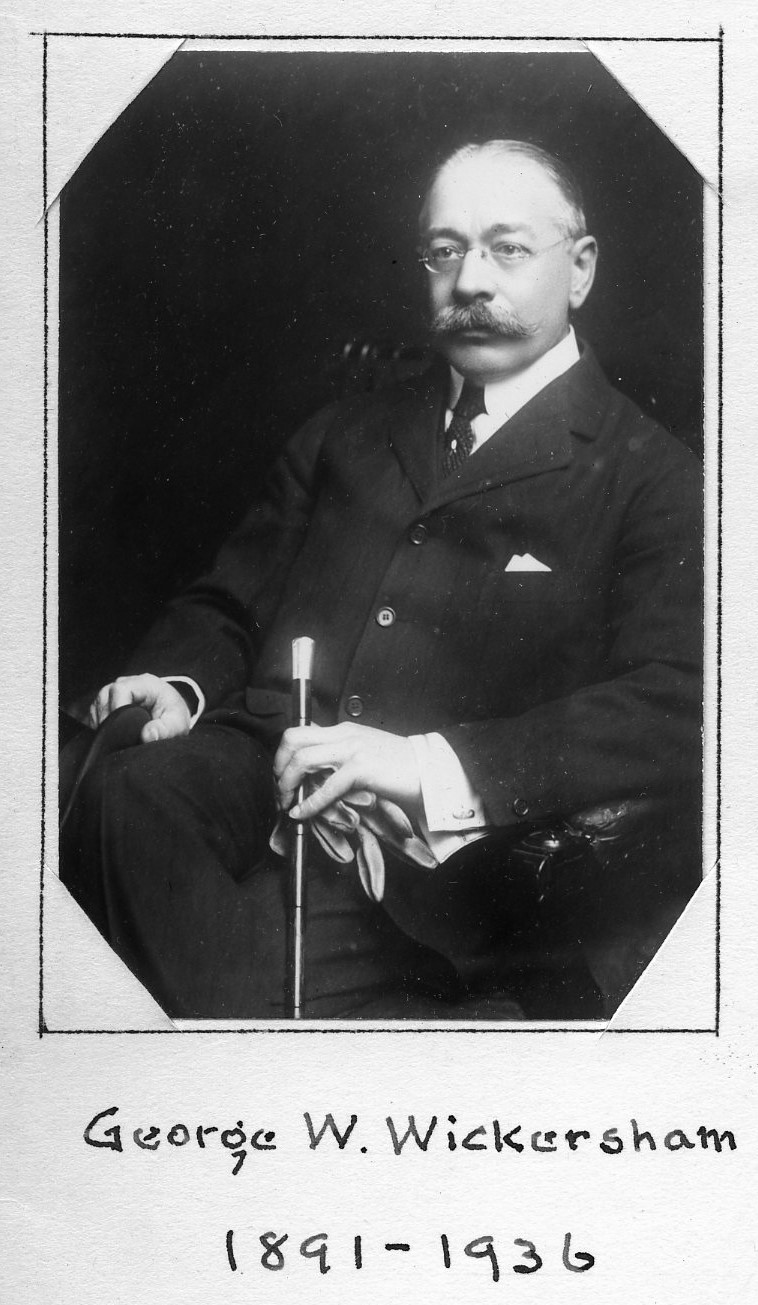

Lawyer/U.S. Attorney General

Centurion, 1891–1936

Born 19 September 1858 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Died 25 January 1936 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Brookside Cemetery , Englewood, New Jersey

, Englewood, New Jersey

Proposed by John L. Cadwalader and Charles Carroll Lee

Elected 3 October 1891 at age thirty-three

Archivist’s Note: Second vice president of the Century Association, 1928–1936

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

George Woodward Wickersham had been a member of the Century during forty-five years; for eight years he had been the Club’s second vice-president. He was almost invariably present at meetings of the Board of Management, where his conversation was always enlivened with a touch of humor and his judgment on controversial questions, expressed promptly and concisely, was always sound. In his practice as lawyer, Wickersham’s qualities were sufficiently remarkable to explain the high place which he won in city and nation. He united, in a somewhat unusual degree, the personality of the old-time “counsel learned in the law” and that of the man of affairs who could disentangle the most difficult of legal complications. His background in the law was illumined with knowledge of literature and history. The raising of a disputed point in either was certain to elicit from him the exact facts of the episode in question, or the exact language of the literary passage. When to this tenacity of memory was added unusual power of clear exposition, his place in the Club and in his profession was undisputed.

His fellow-Centurions will remember Wickersham for his always genial manner, his animated talk, and his instantaneously entertaining response to a humorous turn in the conversation. Probably the public at large will associate him chiefly with his Anti-Trust Law prosecutions as Attorney-General under Taft and with his report as chairman of the Law Enforcement Commission under Hoover in 1931. But it is doubtful if Wickersham’s real quality was justly exhibited in either. He argued successfully before the Supreme Court, and with the public’s full approval, the case against the Standard Oil and American Tobacco combinations and against the Union and Southern Pacific merger. In all he won his case. But his challenge to the United States Steel attracted wider public notice and much less public sympathy. When the courts decided against the government, the public received the verdict with complacency. That was one occasion on which, it may be surmised, Wickersham’s own legal judgment was overruled by what his superiors deemed to be exigency of politics. The Taft Administration considered it not enough to complete Anti-Trust suits initiated under Theodore Roosevelt. It must strike for itself, and the Steel merger was the conspicuous target.

The Law Enforcement report of 1931 examined with convincing thoroughness and lucidity the possibilities of reform in the wide field of civil and criminal jurisprudence; but, quite inevitably as matters then stood, the general public displayed interest only in its recommendations on prohibition law enforcement. It is impossible to suppose that Wickersham had approved insertion of such a sumptuary law in the federal Constitution. Personally he did not disguise his indulgent attitude toward citizens who refused individually to obey the spirit of the Act. But in that matter also, it would seem that the political guess by the administration to whom the report was necessarily submitted, very largely shaped its character. The result was not only highly controversial and contradictory judgment by the various commissioners, whose views did not appear to be recognized in the formal report, but early discovery that the administration had guessed wrong.

For Wickersham, however, these were only passing incidents in a consistent and successful career. His fellow-citizens and his fellow-clubmen will remember the animated presence, the interesting personality, and the sturdy physique which for many years enlisted him among the early-morning horseback riders in Central Park and in Rock Creek Park at Washington. It is the pleasing tradition of the Century to draw the reminiscent picture of its members, largely for what they did but pre-eminently for what they individually were.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1937 Century Association Yearbook