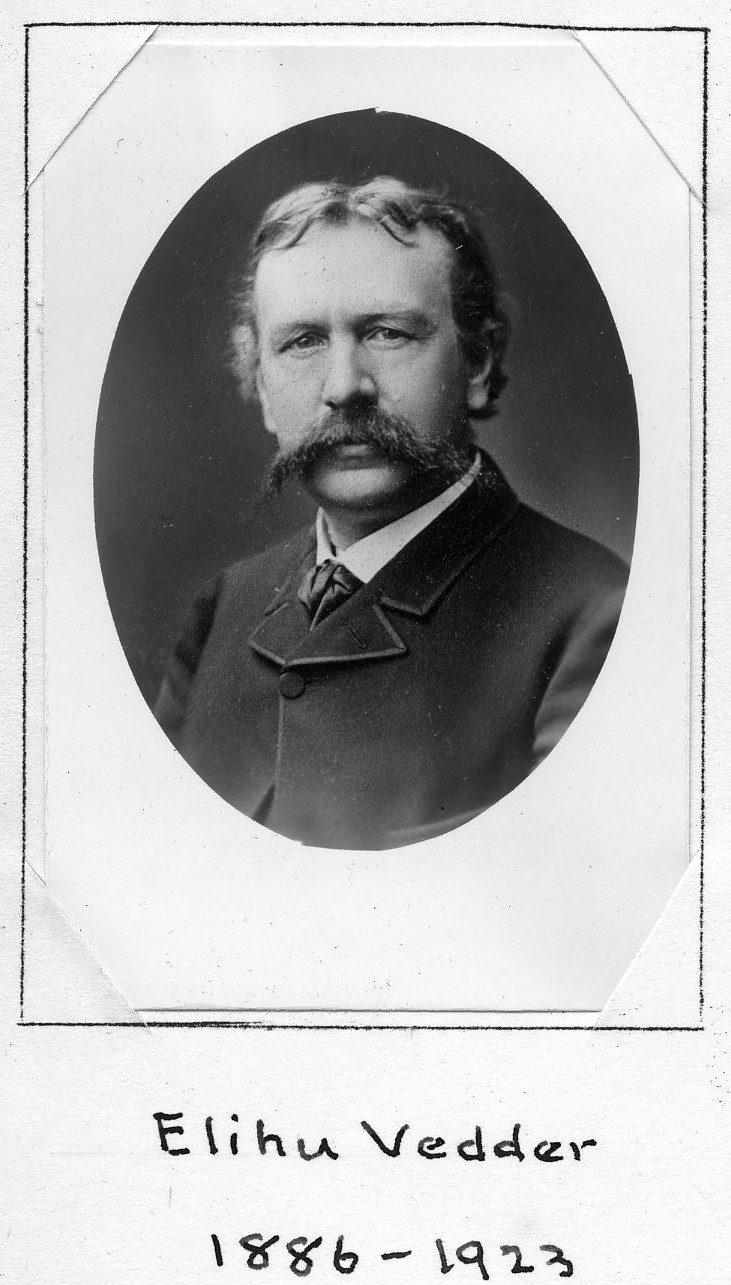

Artist

Centurion, 1886–1923

Born 26 February 1836 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 29 January 1923 in Rome, Italy

Buried Campo Cestio , Rome, Lazio, Italy

, Rome, Lazio, Italy

Proposed by Charles Collins and Eastman Johnson

Elected 6 November 1886 at age fifty

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

To say that Elihu Vedder represented the older generation of American painters would hardly hit the mark. To that older generation an individual certainly belonged whose creative work was begun in 1861, and was exhibited at the Centennial Exposition of 1876 as a mature achievement of American art. But Vedder’s was not the work of an ephemeral artistic school. Perhaps best known to the general public as an illustrator, because of his remarkable artistic interpretations of the Rubaiyat, he was essentially decorative, and in that field of painting never “realistic” in the accepted sense. He seemed to think in big curves of flowing drapery or in bending plants and blowing clouds. At times something of Roman sculpture infused itself into his artistic imagery; at times something of old Norse fancy.

Vedder was cosmopolitan in the broadest sense. A Dutchman by inheritance and an American by birth, most of his life was spent in Italy, where the native painters classified him only as an “artisto straniero”; “the last relic,” so wrote the Giornale d’Italia last January, “of that little group of foreign artists—French and Spanish, Anglo-Saxon and German—who came to Rome as to a city of dream, and brought to the Roman atmosphere a color of sane cosmopolitanism which unified all the tendencies of Roman art into a harmony which today would seem impossible.”

But Vedder also had his very human side. That his personality was full of American crotchets, his two or three books of personal impressions prove beyond dispute. To see him “do” the “broad painter” and the “painstaking painter,” one of his old-time artist friends recalls, “was a favorite pastime of a Century audience and an unforgettable memory.” Appearing at the Chicago World’s Fair as one of the artistic lions, another fellow-Centurion ruefully remarked in 1893, “he entertained every one and did no work. I got him the best order of all that were given and he won’t do a thing.” On the basis of his wonderful conceptions in the Omar Khayyam series a certain well-known publisher, having in view production of an illustrated edition of Pollock’s “Course of Time,” seriously suggested to Vedder the preparation of a frontispiece picturing the Absolute Gazing at the Infinite. It was surely the plain American that spoke out in his reply: “I believe you are making fun of me. I will not give consideration to any such suggestion.”

Even in another continent, Vedder was always a good Centurion. Of the round-robin letter of Christmas wishes, signed by his fellow-members and sent to him at Capri in his last illness at the close of 1922, his daughter wrote that “nothing on earth could have given my father more pleasure. As I read out the names he made remarks on all of them, and expressed so much pleasure at being remembered. I think it has given him a new lease of life.” But that was not to be.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1924 Century Association Yearbook