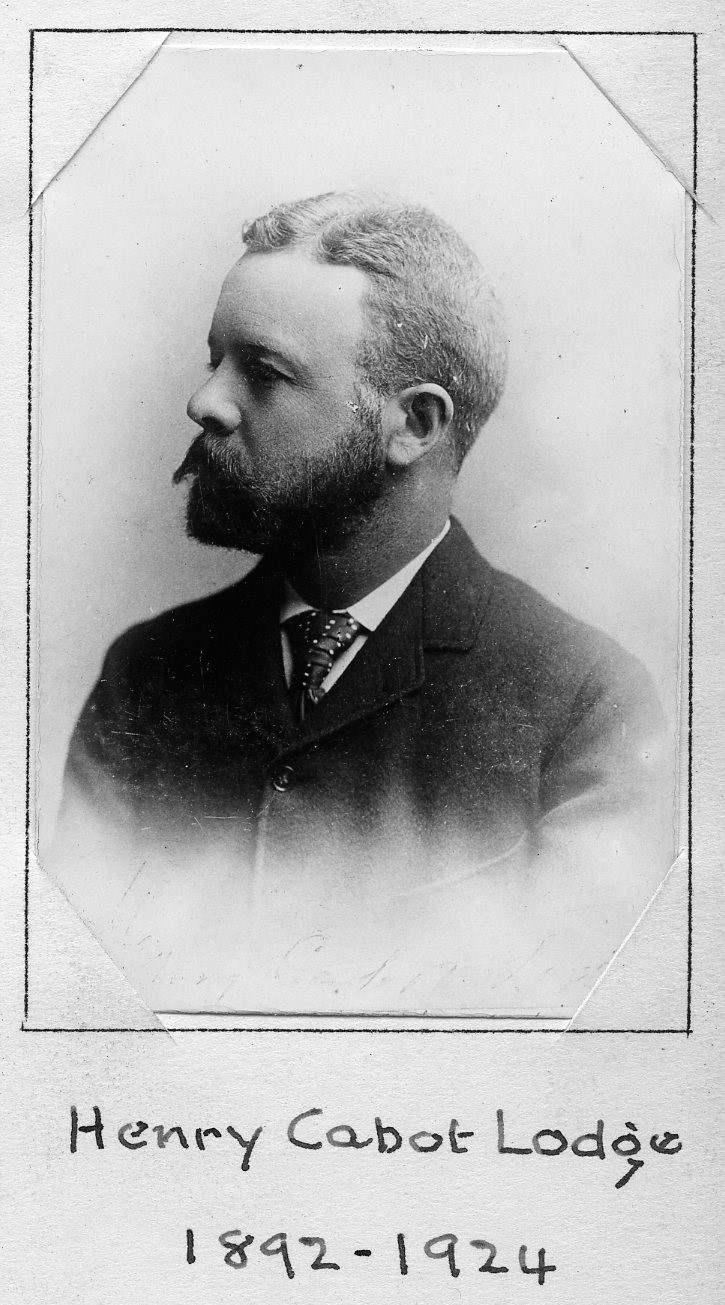

Author/U.S. Senator

Centurion, 1892–1924

Born 12 May 1850 in Boston, Massachusetts

Died 9 November 1924 in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Buried Mount Auburn Cemetery , Cambridge, Massachusetts

, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Proposed by John Hay, Richard Watson Gilder, and Robert Underwood Johnson

Elected 6 February 1892 at age forty-one

Century Memorial

There are coincidences in death as there are in life; coincidences which, occurring with men of mark, will sometimes emphasize the fact of the ending of an era. Our schoolboy histories used to point out the dramatic touch which the passing of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, on the same Independence Day of 1826, gave to the fact that the old Federalist party had at that date also breathed its last and that the Democratic party, led by new men with new ideas, was about to break with its State rights, strict-construction past. A somewhat similar realization that one chapter of contemporary history has closed and another opened is brought by the death, within the twelve-month, of Woodrow Wilson and Henry Cabot Lodge.

Although both of these well-known statesmen had been long-time members of the Century, neither was a familiar figure at the Clubhouse. Senator Lodge was said to prize his membership mostly as a mark of affiliation with the best intellectual group in New York City; Mr. Wilson was apt to visit the Club, on the rare occasions when he came, as a refuge from the exigencies and annoyances of politics. A few surviving Centurions will recall in 1912 the Sunday before Labor Day—the zero hour of Presidential battles—when Governor Wilson, then the Democratic candidate, sat at the Club’s dinner-table and frankly unfolded, to the one or two fellow-diners who had been left behind in the holiday exodus, his personal apprehension over what seemed the irresistible rolling ball of popular favor for the Third ticket and Mr. Roosevelt. It was a curious moment in campaign psychology, coming as it did at almost the very day of the campaign on which, in 1864, Mr. Lincoln sealed up for his cabinet the identical notes declaring his personal judgment that “this administration will not be re-elected.” Perhaps it needed the confidential atmosphere of the White House or the Century to make possible, at such a moment, such confessions of political misgiving.

Wilson and Lodge were outstanding figures in the epoch of American history which may be said to have begun in 1914 and to have ended perhaps in 1920, perhaps in 1924. Neither was identified exclusively, however, with the events of the intervening period. In Wilson’s case especially, future history will hardly overlook the reform of the currency in 1913; the establishment of the Federal Reserve, under resolute pressure from the new Democratic president and not without co-operation of the Senator from Massachusetts. Lodge’s championship of international copyright will similarly be remembered. But in the public mind, both men will be primarily associated, first with the episode of our attempted neutrality in the European war, then with our amazingly effective and triumphant participation in the struggle, then with that strange peace convocation in which the President of the United States seemed to reach the highest pinnacle of international prestige and personal authority in modern history, and at last with that other legislative battle which ensued at Washington, of which it is possible to say that while one side was overwhelmingly defeated the other side did not win.

We are even now too near to that embittered conflict to be sure just how far the legislative battle of 1919 was actually fought on the merits of the general issue, which was American participation in a union to preserve world peace, and how far it was fought on the incidents, passions and personalities of the day. Personal failings and personal mistakes had much to do with the controversy, and both protagonists were far too well-versed in political history not to recognize the fact. Reviewing, many years before 1919, the closing administrative days of our first president, Mr. Lodge cited the accusations of an excited Opposition that Washington’s conduct had been “improper and monarchical” and had “violated the Constitution”; described the refusal of Congress to follow the previously unbroken precedent of visiting the White House on the President’s birthday, and then remarked that “party feeling could hardly have gone further”; that “this single incident is sufficient to dispel the pleasing delusion that party strife and bitterness are the product of modern days.” Describing in his “History of the American People,” published long before the war, the wrecking of another American president’s public policies by the Senate, Mr. Wilson wrote that “a more moderate, more approachable, . . . less headstrong man might by conference have hit upon some plan by which his differences with the leaders in Congress would have been accommodated.”

Alexander Dana Noyes

1925 Century Association Yearbook