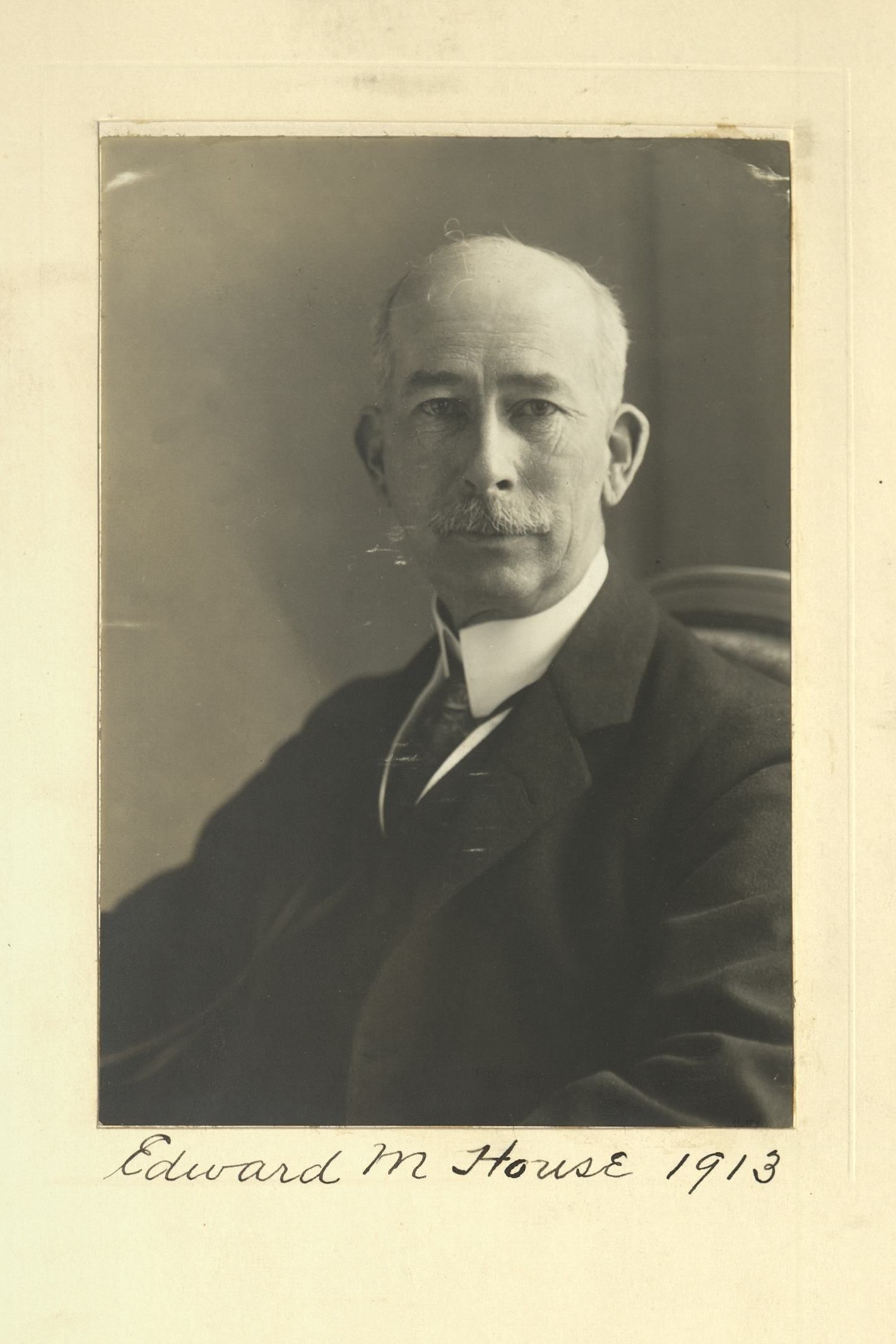

Planter/Publicist/Diplomat/Presidential Adviser

Centurion, 1913–1938

Born 26 July 1858 in Houston, Texas

Died 28 March 1938 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Glenwood Cemetery , Houston, Texas

, Houston, Texas

Proposed by Edward S. Martin and Cass Gilbert

Elected 6 December 1913 at age fifty-five

Century Memorial

It seems appropriate to set down the fact that those who remember the rare occasions upon which Col. Edward Mandell House entered the Century Club, recall chiefly his silence. Elected in 1913, he was a Centurion throughout the period of his unique and distinguished public career. He was always the center of conversation when in the club-house. John J. Chapman would lead a vigorous attack in an effort to learn something about what was going on in President Wilson’s mind. House would listen attentively, absorbing all the fire—and return hardly a shot. He was too gentle and kind, too clearly the straightforward American, to be called mysterious. Yet no one in our history stirred in his lifetime so much bewilderment or has since caused the historians as much speculation and doubt as centers about the name of this paradoxical figure of a great period.

The essential mystery of Colonel House centered, of course, about his extraordinary relationship with President Wilson. The problem has puzzled the historians and is still far from solved. Colonel House has been portrayed as the guiding genius of the Wilson presidency, as if he were, indeed, one half of a single nature formed by a mystical fusion of two individuals. In the height of their friendship, their interchange of intimate notes lends color to such a fantastic theory. On the other hand, the Colonel has been written down by certain critics as no more than a confidential messenger—who in the end forgot his master’s orders and sought to act as a free agent. Neither extreme of interpretation can well be the truth. The former does less than justice to Wilson, the second less than justice to House. It may well be that the complete disentanglement of so close a friendship is a matter of years and long perspective.

It can be forcibly argued that had the House sagacity prevailed at Versailles, the course of history might have been profoundly changed for the better. But at this precise moment, in the climax of their joint career, the delicate adjustment of these two singular personalities jangled and broke down. The Colonel’s technique of self-effacement failed in its purpose. Perhaps the task of remaining a silent and minority partner in this strange firm proved too great. Perhaps Wilson had risen above the possibility of accepting such intimate advice. Whatever precisely happened, the mystical cord snapped. Thenceforward the President marched alone.

Regardless of what the historians may decide touching this difficult problem, there can be no question of the central verdict as to House: He was an utterly sincere soul, striving with singleness of mind for the right as he saw it, and his loyalty alike to his President and to his country was without stain.

Geoffrey Parsons

1938 Century Memorials