Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

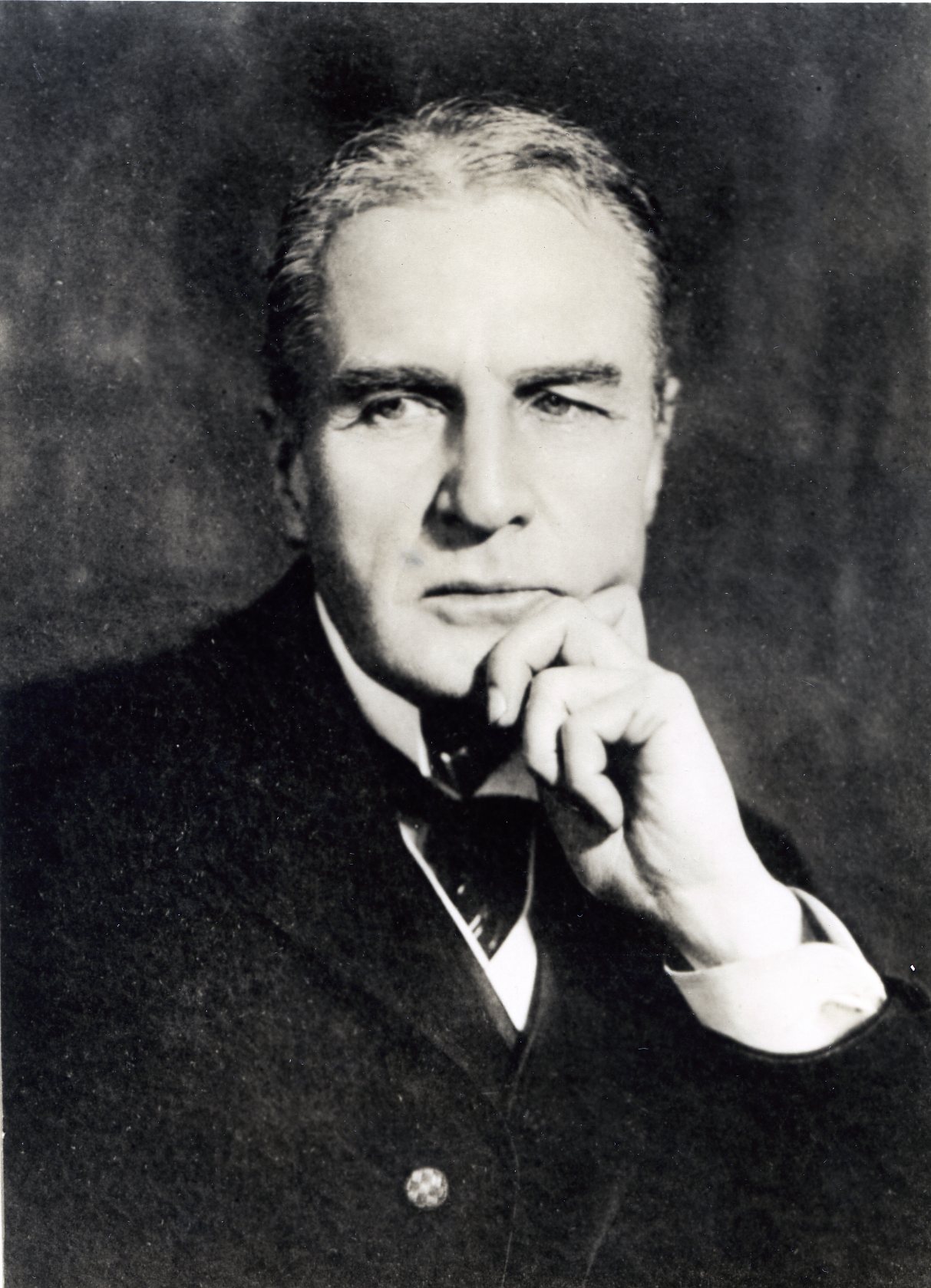

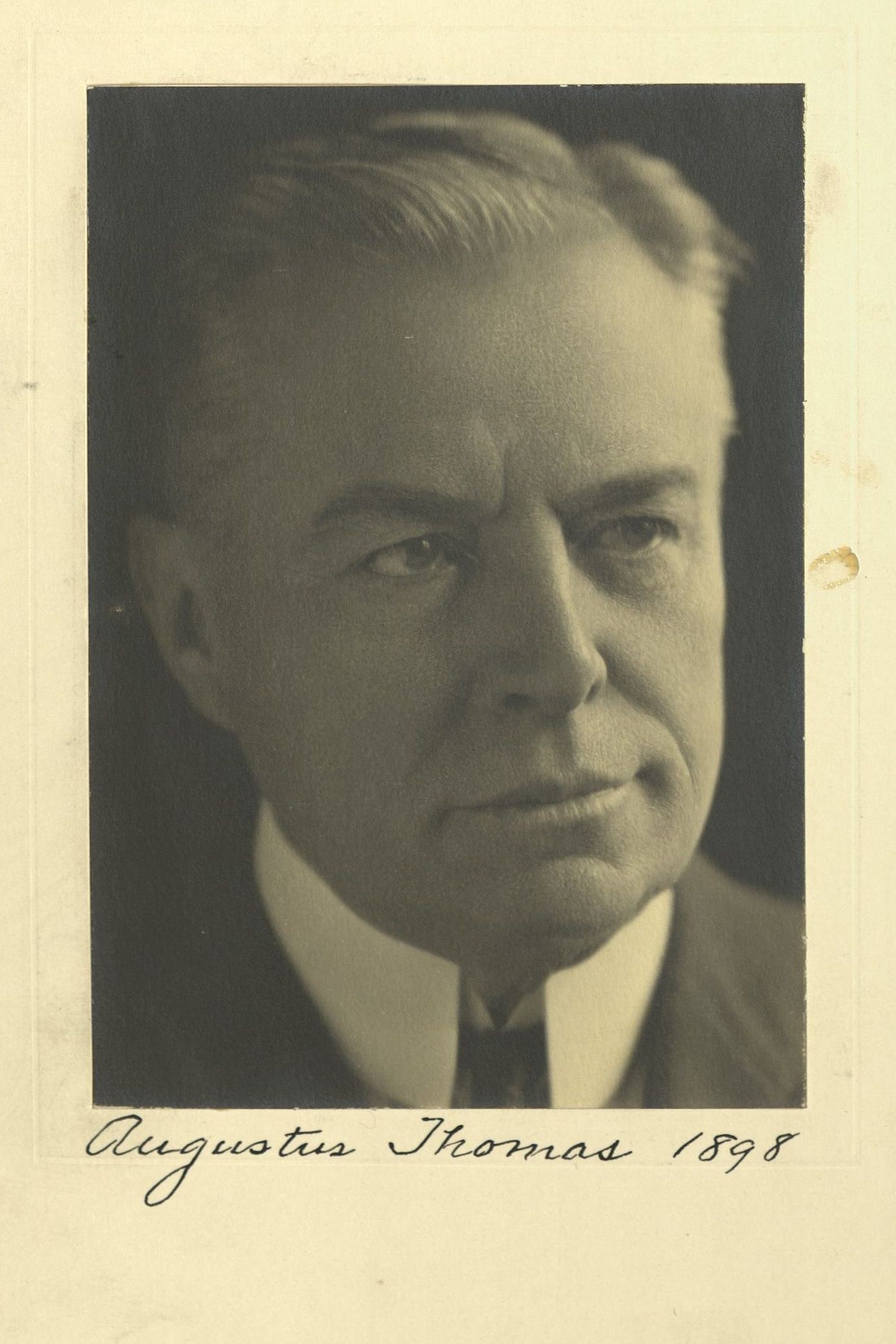

Augustus Thomas

Author

Centurion, 1898–1934

Henry E. Howland and J. Pierpont Morgan Jr.

Saint Louis, Missouri

Nyack, New York

Age forty-one

Saint Louis, Missouri

Century Memorial

The Century will best remember Augustus Thomas as the most genial among club associates, spirited conductor of an older Twelfth Night revel, master of dry humor and amusing anecdote, always delivered with a serious face. Outside the Club-house, what he called his own profession knew him as one of the most productive and successful playwrights of the past generation. Yet if chance and doubtless strong personal inclination had not directed him to the drama, Thomas might have diverged so far from that field of usefulness as to have become a politician. His life program must sometimes have seemed to have been arranged for that. Serving as page in the House of Representatives during 1870 and 1871, Thomas obtained at an early age, and much after the fashion of Ike Hoover, impressions as to what qualities made for political success. It has to be admitted that the era of James G. Blaine, Ben Butler, Roscoe Conkling, George S. Boutwell and Thaddeus Stevens hardly provided the education of a statesman. Nevertheless, possessing a good voice, an easy manner and an infectious humor, Thomas owned up to having made campaign speeches in every Presidential year from the middle Eighties onward. His childhood background was itself a mixture of political with theatrical reminiscence; his own remembrance, as an eight-year-old boy, of how the news of Lincoln’s assassination came to the family circle at St. Louis, was deeply colored by the fact that John Wilkes Booth had been his father’s friend and a favorite of the family.

Thomas was so many-sided in his earlier activities that he might have attained celebrity as draftsman or caricaturist. The larger editorial career was distinctly opened to him by his work as news reporter at St. Louis, and by the subsequent outright offer to him of the leading place on daily newspapers at Leavenworth and Kansas City. With all recognition of Thomas’s versatility, it is hard to conceive him analyzing for trustful readers the complexities of a political or economic situation. But as a matter of fact, all of these avocations were disturbed and interrupted by dramatic composition, a field in which Thomas quickly came into his own. Between 1875 and 1921 he wrote and produced no less than sixty-one separate plays. Of these, perhaps a dozen were one-act sketches and another dozen dramatization of published books; but many of them, like The Witching Hour, the Earl of Pawtucket, Colonel Carter of Cartersville, Mrs. Leffingwell’s Boots and In Mizzoura, had a long run of popularity and introduced to the American stage some of our best-known character actors. Today, no doubt, our enlightened dramatic critics would describe a “Thomas play” as obsolete or mid-Victorian. He himself recalled, in after years, that he achieved his first great success before the footlights while Rosina Vokes was delighting sophisticated New York with “My Milliner’s Bill”; while Maude Adams, an ingénue of sixteen, was charming her audiences in “The Midnight Bell”; while Sothern played “Lord Chumley” and theatre-goers crowded to hear Denman Thompson in “The Old Homestead.” It was a day of simple conceptions for the drama; yet, somehow, orchestra circle and balcony derived a pure enjoyment which is denied to them by present-day theatrical depiction of sex-complications and morbid introspection.

Thomas had little interest in this later notion of the drama. The stories on which his own plays were constructed had to do with the plain and usually humorous experience of real life. Often they pictured the eccentric, whether of character or incident. Always they presented a sharply-outlined and convincing portrait for his leading parts. Traveling, as he often did with his companies on the road, it followed quite inevitably that Thomas should have delighted in reminiscence of older-time theatre life. He recalled with his own characteristic humor the occasion on which a professional acquaintance invited him and Barrymore to dinner, provided them with a Lucullus feast at thirty-five cents for the table-d’hôte and asked, triumphantly, if that was not a bargain; also Barrymore’s response that “It surely is; let’s have another one.” His own approach to a Chicago hotel desk in the early Eighties, with his theatrical troupe behind him, was a vivid picture; the clerk who named the rate of “three dollars, American plan,” but who, having been anxiously asked by Thomas “What is your professional rate for actors?” responded, gazing into vacancy, “That will be three-fifty.” Perhaps he was fondest of the incident which was told in those older days, and which Thomas often retold, of Bill Nye and James Whitcomb Riley in their joint “lecture tour” at one-night stands, when Riley, having inspected the audience beforehand through the curtain, reported with consternation that “there are not twenty people in the house.” Bill Nye, engaged in the last manœuvres with a white dress-tie, responded: “I don’t understand that at all; we have never been here before.”

Thomas delighted in such professional remembrances, but it is his own personality that the Century will remember. In the long list of Centurions of our day, few are surrounded with a pleasanter retrospective picture than attaches to the erect figure, the ingratiating manner, the fund of quiet but always ready anecdote, which marked his frequent arrival at the Club-house.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1935 Century Association Yearbook