Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

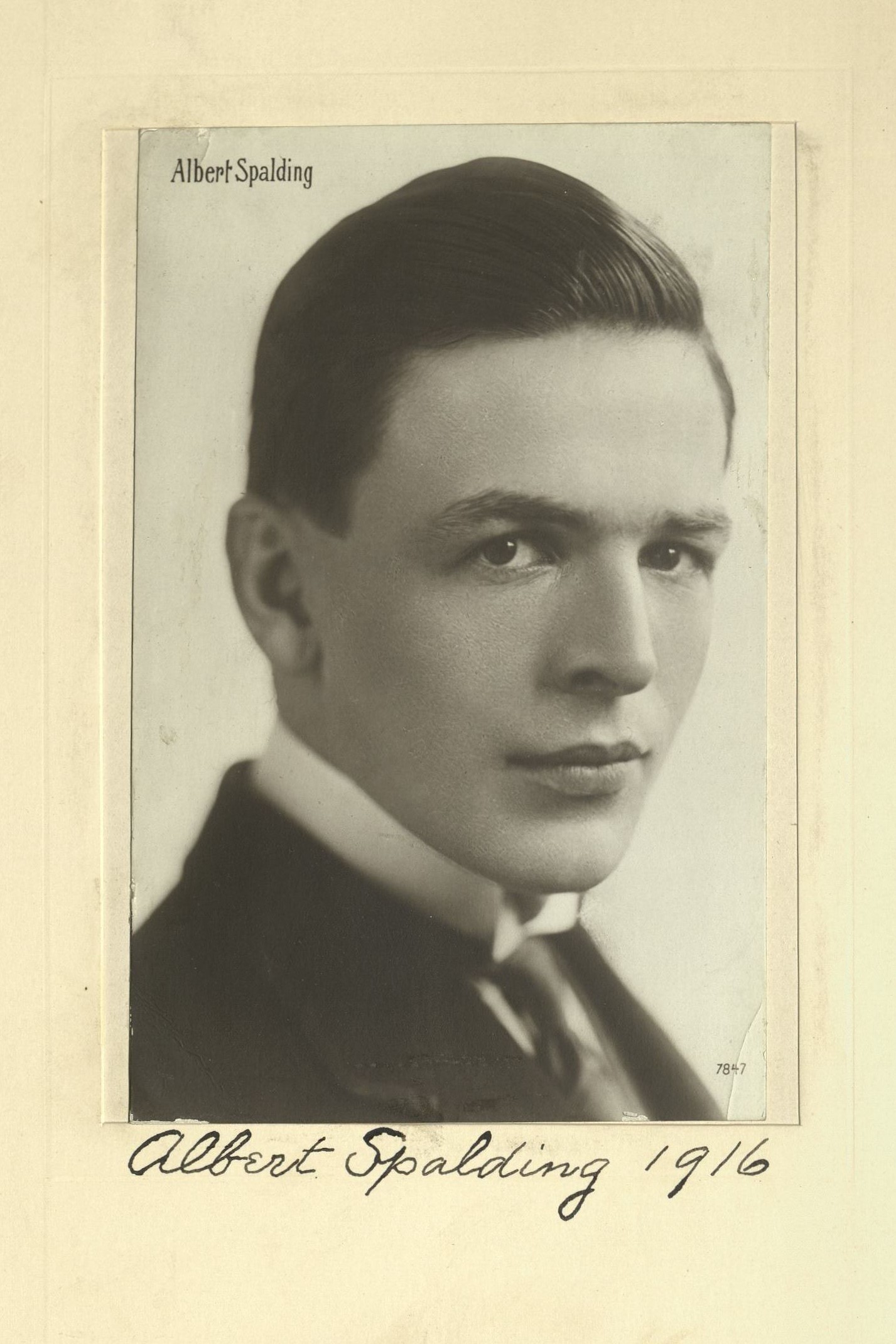

Albert Spalding

Musician

Centurion, 1916–1953

Arthur Whiting and Charles A. Rich

Chicago, Illinois

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age twenty-seven

Century Memorial

Albert Spalding was elected to the Century in 1916, when he was but twenty-eight [sic: twenty-seven] years old. He was a violinist—the greatest American-born violinist that has ever been.

His father, J. Walter Spalding, and his uncle, A. G. Spalding, were partners in A. G. Spalding & Bros. His mother, Marie Boardman, maintained a music salon in Florence for many years. When Albert was seven years old, he asked for a violin for Christmas. When it arrived, it was a half-sized instrument that cost $4 and was intended as a joke. But the boy would not put the little fiddle down, and after a while lessons were started. At fourteen he graduated from the Bologna Conservatory—the youngest alumnus since Mozart.

The pathway to artistic recognition was actually more difficult for Spalding because he was so very much an American. In his time, indeed for all his life, almost all of the great violin virtuosi beloved by Americans were foreign born. He crossed the Atlantic more than two hundred times, and Europeans became aware, before Americans, that here was a violinist of the very first quality. Furthermore, he did not seem to act the part. Musicians are thought of as being a tribe characterized by long hair, ill-fitting clothes, and erratic temperaments. Spalding was conservative and immaculate in appearance. In the First World War, instead of touring rest camps with a troupe, he put away his violin and was commissioned a line officer in the Aviation Corps, serving in Italy. In the Second World War he returned to Italy to serve in the psychological warfare branch of the Army. He was one virtuoso who did not use a Stradivarius. His favorite instrument was a Guarnerius dating from 1735.

This distinguished citizen served his country in two wars, and in times of peace brought luster to his nation. His achievement was the finer because it was completely divorced from anything remotely resembling showmanship. When he played, he became absorbed, and the violin became a part of him, expressing aloud an inward and spiritual grace. There are some things too wonderful for us: the way of an eagle in the air; the way of a serpent upon a rock; the way of a ship in the midst of the sea; and the way of a man with a maid. And to these should be added the way of the bow with the viol: well-spring of ecstasy, which only the violinist himself can drain to the lees:

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

George W. Martin

1954 Century Association Yearbook