Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

J. Sherwood Seymour

Publisher, Evening Post

Centurion, 1920–1924

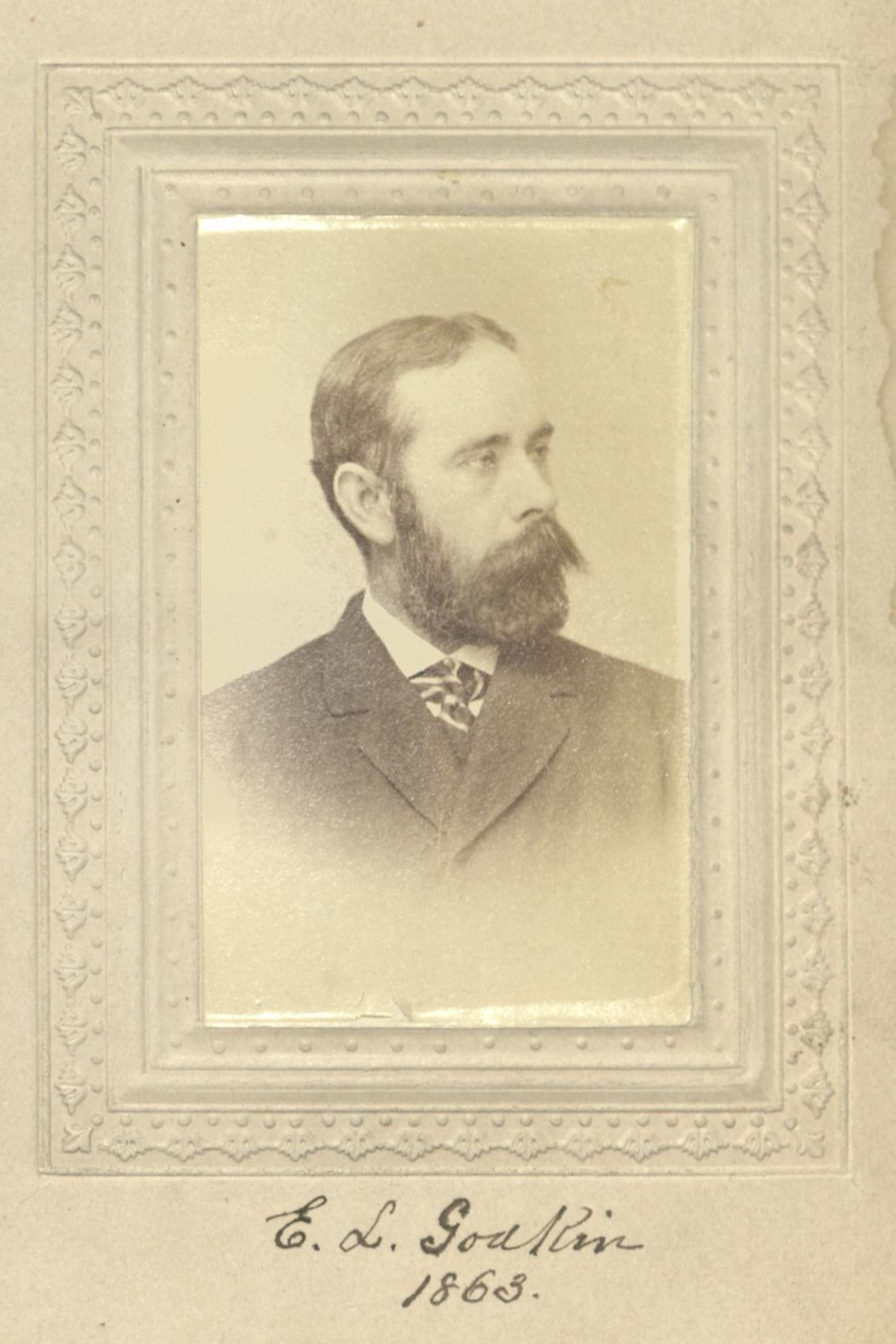

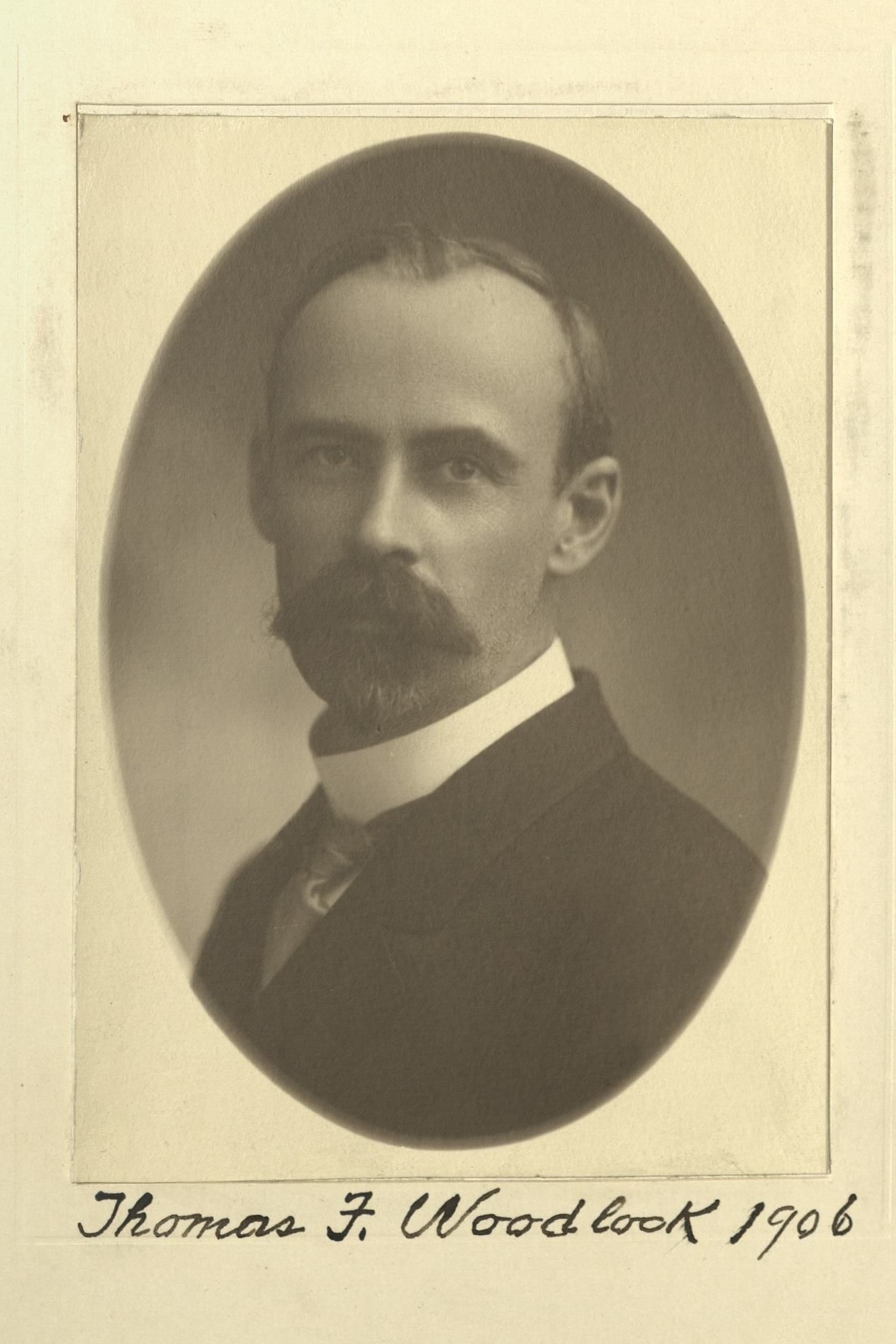

Thomas F. Woodlock and Charles C. Burlingham

Bloomfield, New Jersey

Bronxville, New York

Age fifty-five

Bloomfield, New Jersey

Century Memorial

James Sherwood Seymour embodied in his business career the best traditions of the modern newspaper publisher. That profession has always had its particular temptations. In older days, and to a lessening extent at a more recent time, the temptation was to use a newspaper’s power of publicity, whether by offer of favors or by threat of exposure, to coerce the potential advertiser. Today the temptation is to use the counting-room’s influence with the editorial department for evasion or suppression of comment unpalatable to existing advertisers. In mastery of the details of his profession, Seymour stood in the front rank. He achieved notable success, alike in making the old Evening Post a profitable enterprise, in extending the circulation of the Chicago Record-Herald, and in setting on its feet for a new prosperity the American Magazine. But he had to meet the test which sooner or later confronts all men engaged in his field of journalism, and very few American newspaper publishers have met it with his courage and decision.

To him the editorial page was the palladium of the newspaper. Its freedom from interference must at any hazard be protected. It was the business of the publisher to see that those columns should be free from even the suspicion of outside interference. How he succeeded, the reputation for absolute independence, enjoyed by the Evening Post of his day and Godkin’s, is sufficient witness. Seymour’s former colleagues will remember the occasion when an advertiser of some importance wrote to the publisher, objecting to a certain policy of the newspaper and intimating that, if the policy were continued, he might feel constrained to withdraw his advertising. When the letter came, Seymour was standing by the “make-up form” in the composing room. He first directed the maker-up to lift from the form the advertisement referred to. Then, calling his secretary, he dictated a note to the advertiser, informing him that his favor of even date had been received and that, unless he promptly apologized for his letter, the advertising columns of the Evening Post would be permanently closed to him. The apology came next morning. It is men like that who help us to understand that there is a best as well as a worst in modern journalism.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1925 Century Association Yearbook