Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

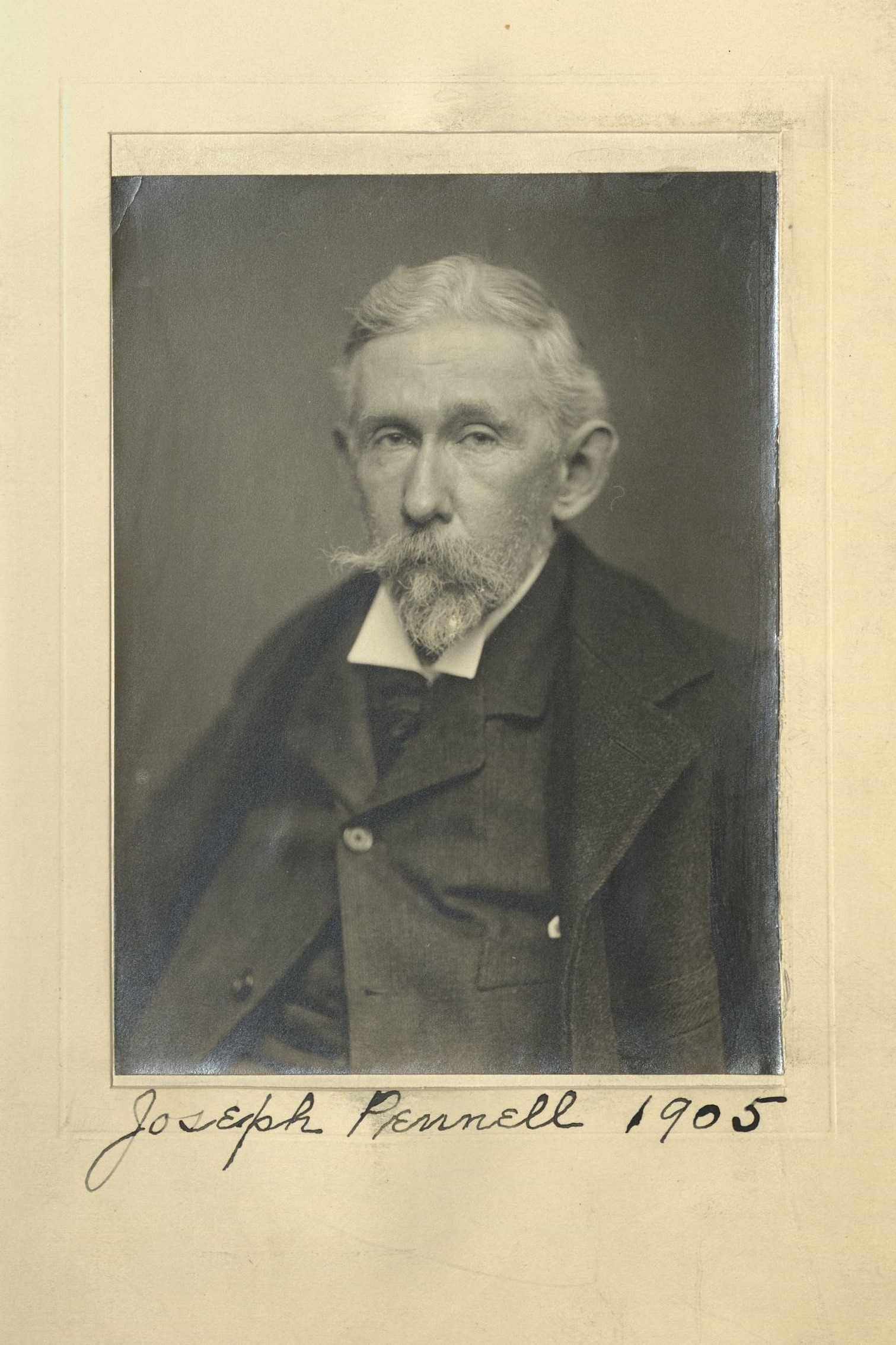

Joseph Pennell

Artist

Centurion, 1905–1926

Frederick Dielman and Carlton T. Chapman

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

New York (Brooklyn), New York

Age forty-eight

Germantown, Pennsylvania

Century Memorial

If Joseph Pennell has been called a disciple of Whistler, it is because he saw that, of all the great etchers, Whistler’s conception of the art was nearest his own, and because he found the surest development of his craftsmanship by treading the path marked out by Whistler. But he was in no other way a follower; the distinction of his work is its originality. He told his own pupils later on that, whatever they did, they were “not to make Pennells.” There was nothing in the scenery of common life which his illustrative pen and tools could not surround with an atmosphere of poetic imagination. Whistler had drawn the London docks; Pennell’s sketches ranged from the Rouen Cathedral, the Grand Canyon in a storm, and the hillside of LePuy, to London’s river-front in twilight, the Liberty Statue darkening New York Harbor’s horizon, the Gatun Lock at the Isthmus, the Mauretania in dock, even the Schneider gun factory and the steel frame rising from the foundations of a New York skyscraper. If, indeed, his imaginative fancy lent itself with particular readiness to any one achievement, it was portrayal of the romance, the latent dignity, of industrial “mass production.” He thus became the interpreter of the characteristic quality of Twentieth-Century America.

This can hardly be assumed to mean, however, that Pennell was individually in sympathy with the civilization of his day. The cranes and shovels, the army of workers on the Culebra Cut, he did indeed describe as “apotheosis of the wonder of work,” a “magnificent arrangement of line, light, and mass.” But that was the artist’s eye. Outside his art, he did not get along very well with this world of ours. Much of it fretted and annoyed him. Nobody else could have taken exactly the view of the Great War that Pennell sets forth in his book of reminiscence. It was to be expected that his scorn would be visited on the military machine that bombarded Gothic Cathedrals; but to Pennell even the American travelers helplessly stranded in belligerent Europe during August, 1914, were simply nuisances and his own appointment by Page to the relief committee an imposition. Pershing and his advance guard of 1917 at Paris brought a “lust for fighting”; as for Pershing himself, Pennell “shuddered as he smiled.” The war “was a show,” but “the world is ruined.” For the nations that were in the war, “it was the beginning of the end of all.” Pennell’s Quaker bringing-up cannot wholly account for these vagaries; his mentality (again outside of art) had plenty of the contentious in it. But those are eccentricities, remembrance of which will fade with time; it is his work which will survive him.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1927 Century Association Yearbook