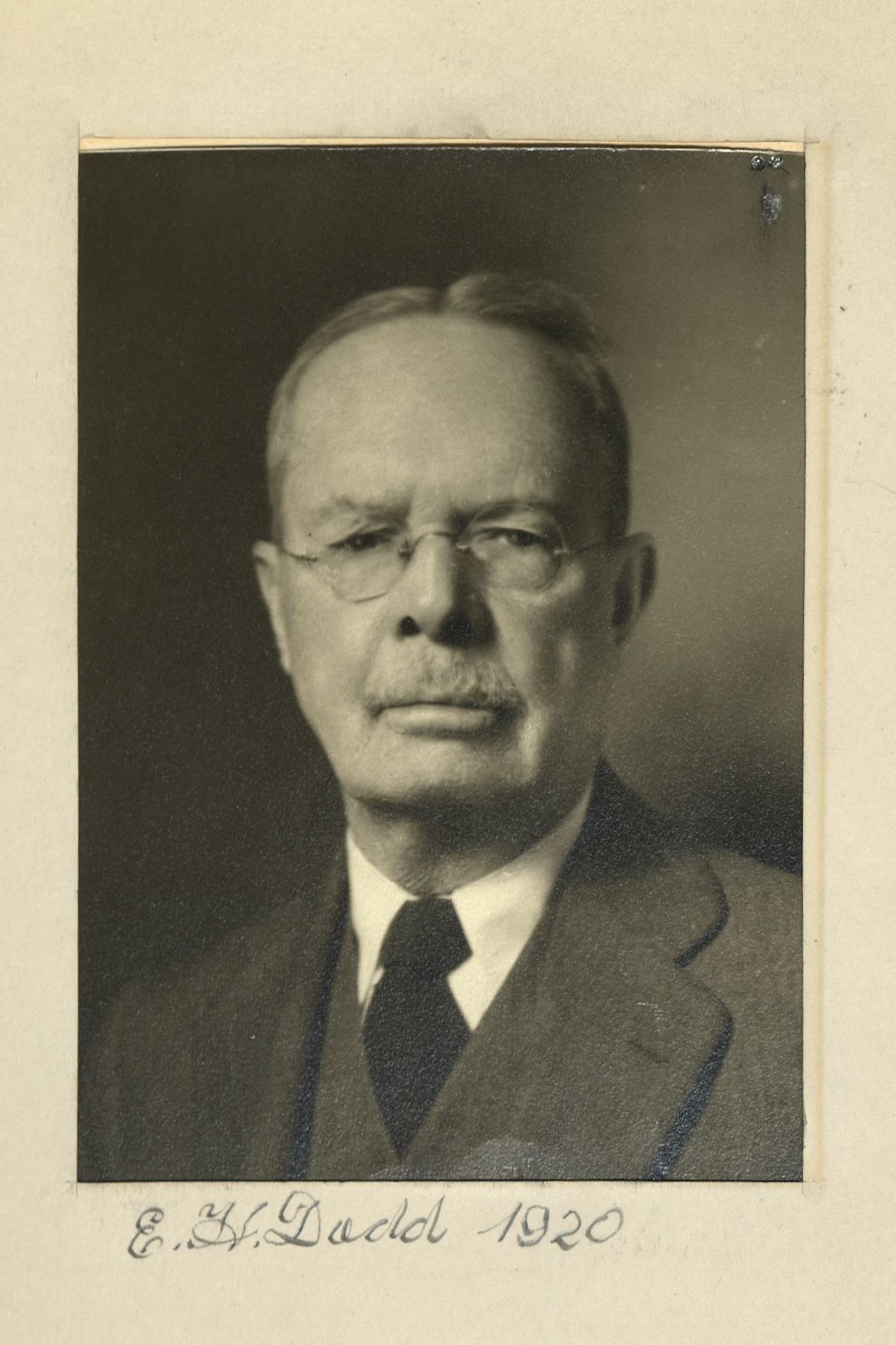

Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

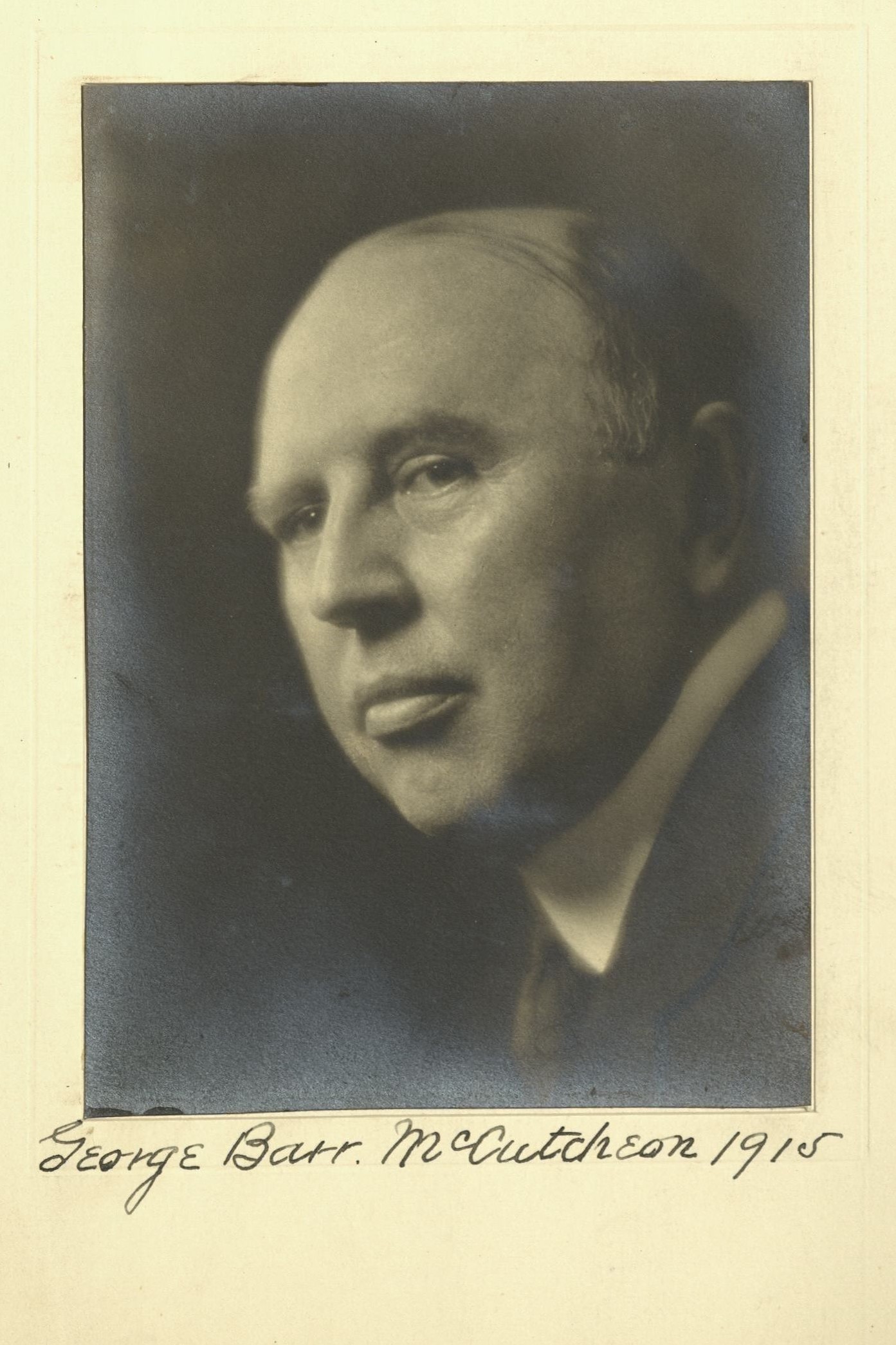

George Barr McCutcheon

Novelist

Centurion, 1915–1928

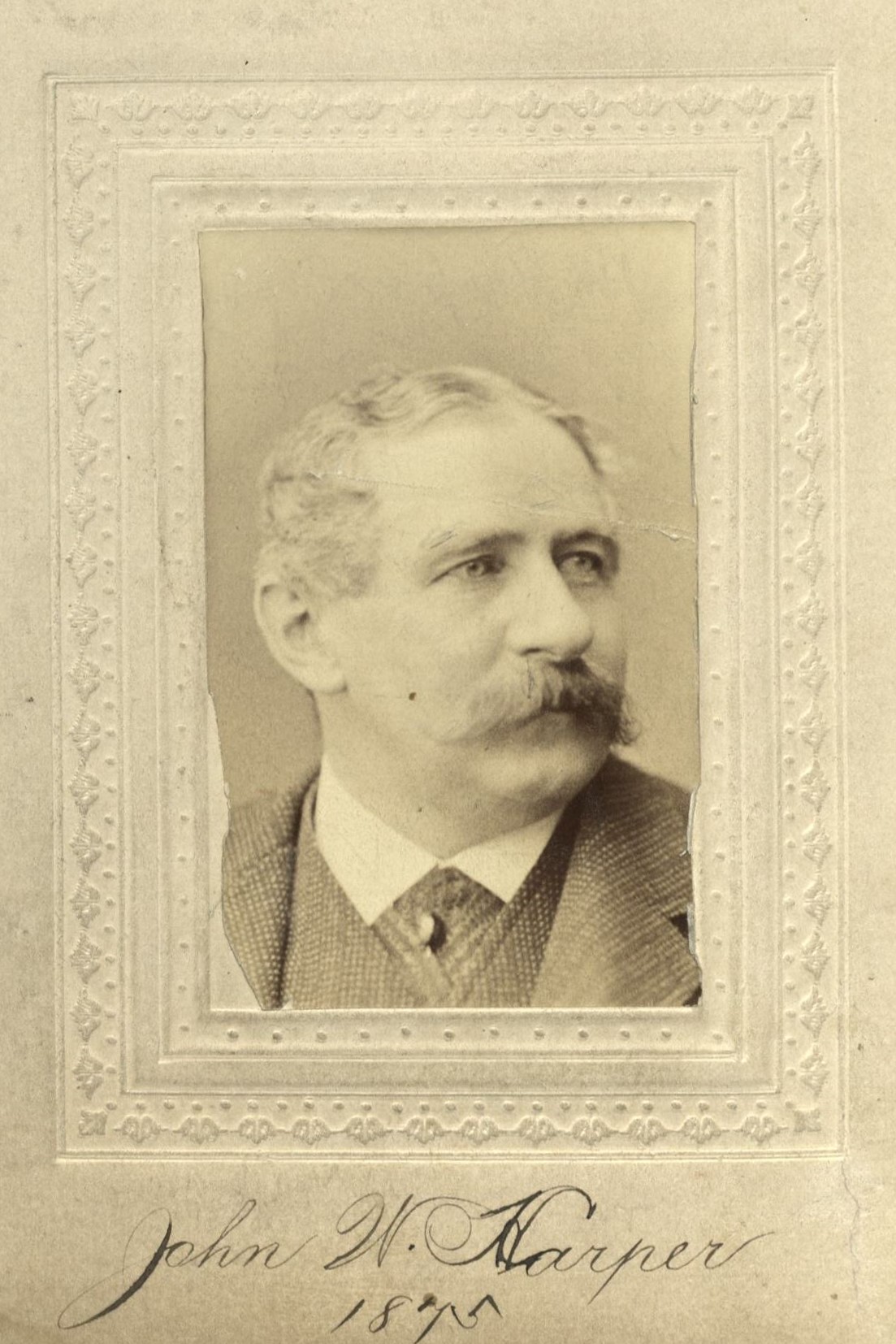

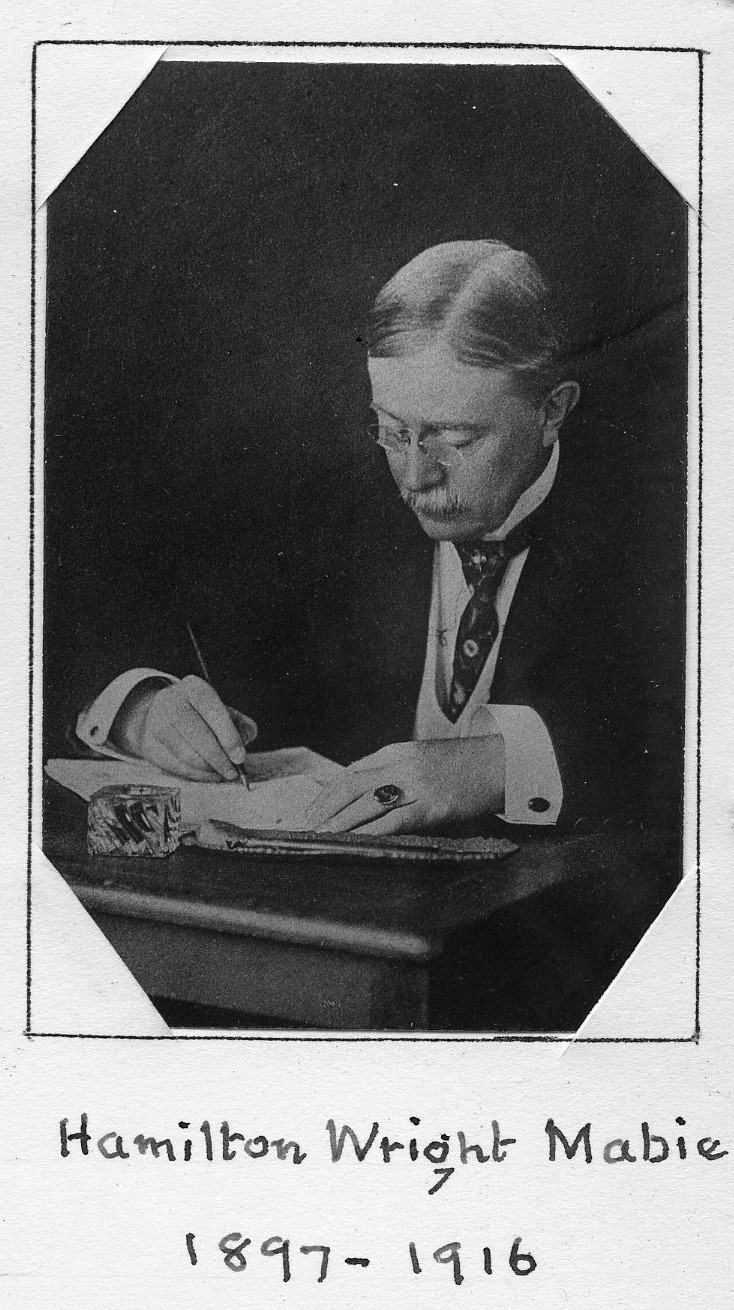

Hamilton W. Mabie and John W. Harper

Lafayette, Indiana

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age forty-nine

Lafayette, Indiana

Century Memorial

The reading public seems to take mischievous pleasure in occasionally shattering conclusions of the literary pundits concerning the books that interest it. No sooner has an elaborate theory been established that nobody any longer reads tales of adventure and exciting incident, that even Scott and Dickens and Thackeray have ceased to appeal to the public’s palate, than a series of slapdash thrillers elbow aside the novels of grave and serious purpose which were alleged to have got exclusive possession of the public taste. The more the new productions violate all conventions of the prevalent literary school on such occasions, the warmer the welcome to them. George Barr McCutcheon was one of the story-writers whose achievement as “best seller,” a quarter of a century ago, shook the belief, then widely cultivated, that the reading public wanted nothing but stark realism. The realistic novel certainly held the centre of that period’s highly respectable literary stage, precisely as the problem novel and the novel of social dullness came to hold it, a generation later. Fiction that consisted merely of good stories was looked upon by the critics and the right-minded public with the superior contempt which Wagnerians bestow on Verdi and Bellini. But whether the taste of the average fiction-reader had not actually changed at all, or whether he had bored himself with the realistic novel in order to preserve a proper social status and had become rebellious, or whether he merely longed for a change of literary diet, at all events the public rushed shamelessly in to buy McCutcheon’s highly imaginative stories.

There was nothing realistic about McCutcheon. Those were days in which royalty still possessed a glamo[u]r that it has mostly lost since 1918, yet had been brought down rather closer to common things by the period’s rise and fall, personal difficulties and social escapades, of the little Balkan potentates. It was opportunity for story-writers who could first put their own Graustarks and Ruritanias on the map of Europe, then describe the intrusion of the masterful English or American commoner into the charmed circle; teaching the king to know his business, making love to the princess, and generally infusing into palace ceremonial the atmosphere of Regent Street or the Middle West. If the tales were not as convincing as Robert Elsmere, that seemed to be a point in their favor. Perhaps the glamo[u]r of just such narratives could not nowadays survive the republicanizing of post-war Europe, the performances at Doom, and the alliance of surviving small-state royalty with families of American metal-trust promoters. But the books were certainly read by the misguided public of their day, and writers on popular ideals had to construct new theories.

Alexander Dana Noyes

1929 Century Association Yearbook