Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

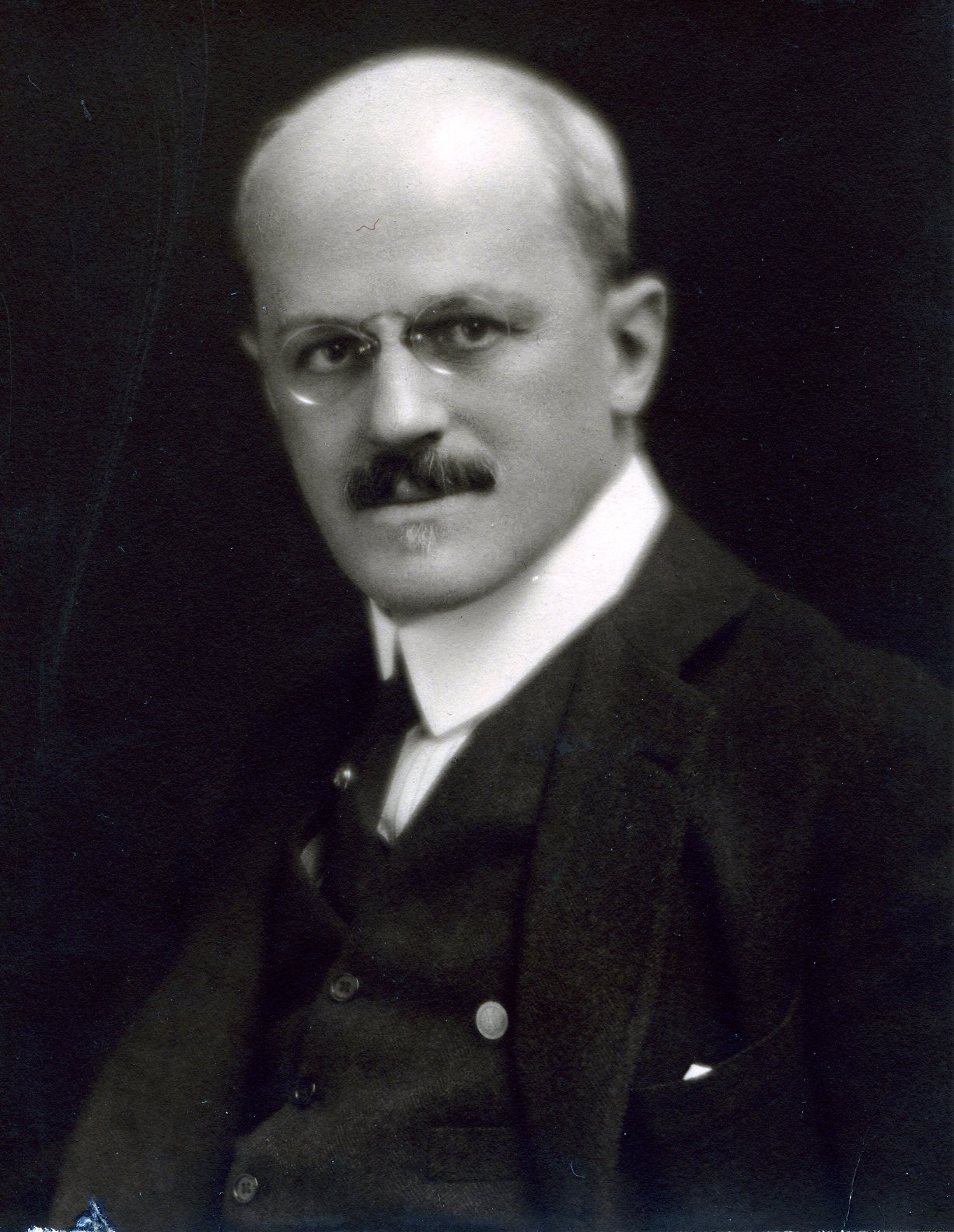

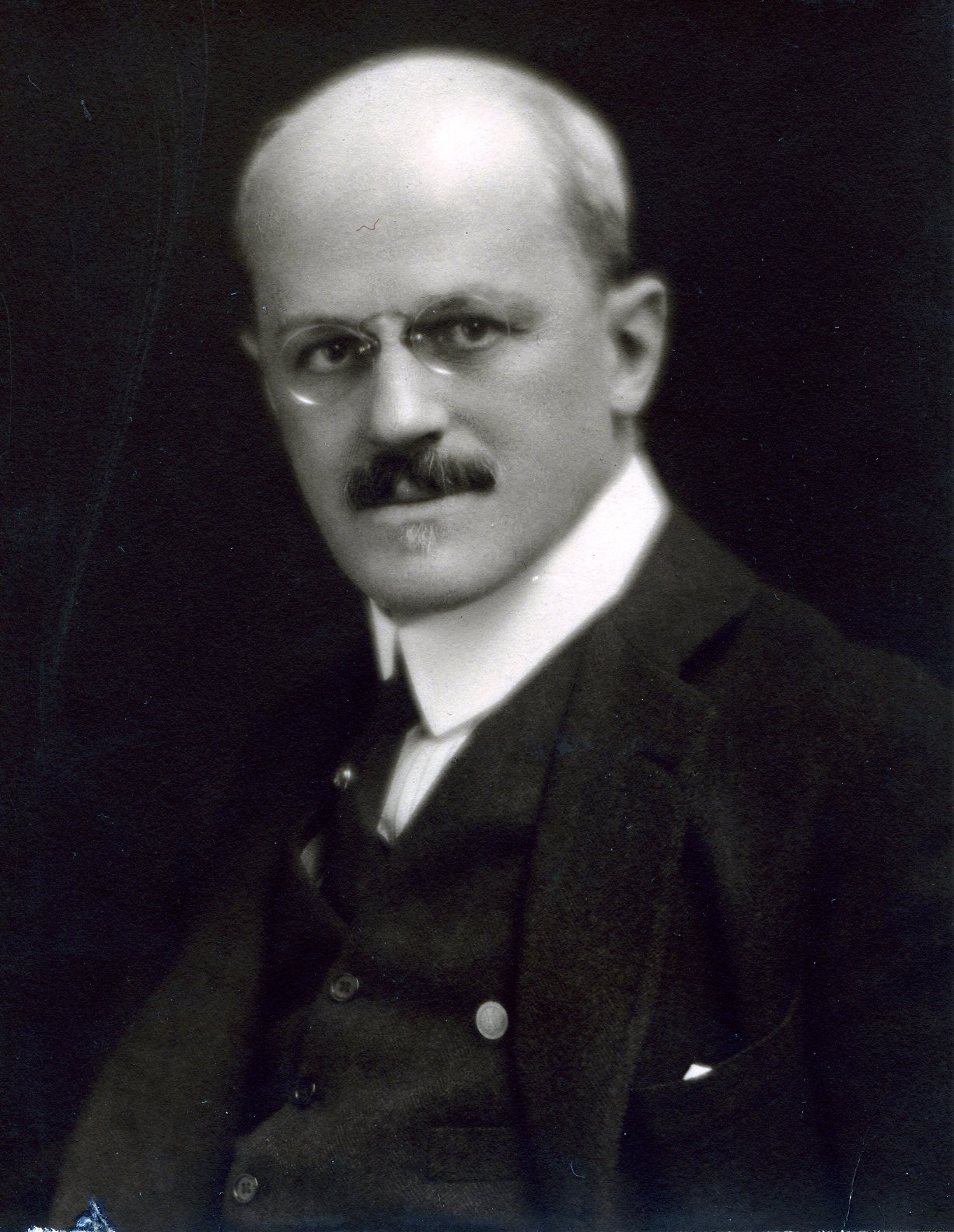

Frederick Paul Keppel

Dean, Columbia College

Centurion, 1911–1943

Hugh Birckhead and Frank J. Goodnow

New York (Staten Island), New York

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age thirty-five

Montrose, New York

Archivist’s Notes

Brother of David Keppel; father of Francis Keppel

Century Memorial

Each of these memorials necessarily represents the point of view of one man, the writer, and thus is bound to be one-sided, which as respects most of us does not matter much; for we are not multi-sided. In the case of Frederick Paul Keppel, however, it does matter, for while it would be far from true to say that he was all things to all men, it is true that he was many different things to many different men, and yet he was always Fred Keppel. The years of many men have been made rich with his presence, his distinctive American character and purpose, his sense of large responsibility, his generous humanity to individual men. The bald record is impressive: the cheer and humanity in it defy documentation, but to one who knew him they are the most impressive part:

Secretary of Columbia University from 1900 to 1910, dean of Columbia College from 1910 to 1918; serving in the War Department as an assistant secretary in 1918, he studied and solved many non-military problems of our army; director of foreign operations of the American Red Cross at the close of the war and first commissioner of the United States International Chamber of Commerce in Paris; returning to New York he became secretary of the committee on the plan of New York created by the Russell Sage Foundation; appointed president of the Carnegie Corporation in 1923, he for nineteen years directed its annual grants, in a total amount of more than $150,000,000; travelled extensively throughout the world studying for the Corporation’s scientific and educational and humanitarian projects; for the past two years member of the President’s Board of Appeals on Alien Cases. Few Centurions have served the Club so constantly: twice member of the Board of Trustees, from 1928 to 1930 and from 1941 to 1943; member of the Committee on Admissions from 1924 to 1926; serving also on the Committee on Literature, the Committee on Art, and the House Committee. In December of 1928 the Board of Management appointed a Committee of Eighteen to raise an Endowment Fund for the Century. Keppel was appointed Chairman. Largely due to Keppel’s vigorous efforts the Committee obtained during 1929 subscriptions for the fund of $201,810.

Sir George Tomlinson wrote in The Times of London on November 25, 1943, of Keppel’s work for Anglo-American understanding:

“It delighted him to think that an agricultural officer in some lonely corner of Africa might use a grant from these funds (Carnegie Corporation of New York) to study anti-erosion schemes in the United States or rice cultivation in Java, but his delight sprang not only from his interest in technical progress, but even more from his faith in the spiritual value of personal contacts in a common cause between workers in widely separated places. In his view such contacts could not fail to forge new, if invisible, links in the chain of friendship and understanding between the parent countries. . . . He was ready to cast his bread upon the waters, firm in the belief that some at least of his ventures would be attended (to quote from his last report) by ‘some reasonably favourable conjunction of the stars.’”

The Carnegie Corporation is the greatest aggregation of capital in the world devoted to cultural and charitable purposes; but the job Keppel loved best was his deaning at Columbia College—for the essence of him was that he was a friend to man. He directed as an affectionate elder brother, he presided over the Carnegie Corporation as the vicar of benevolence; but no man had said a shrewd no to more requests than he, and no man who had said no half as often had left as little rancor behind.

He closed his life as a member of the Board of Review on Visa Cases with a report to the President of the Board’s work which is a great human document of high statesmanship in the unique traditions of our country:

“Fundamentally, the members of the Interdepartmental Committees and of the Board have the same objective. They are equally responsible to protect the interests of the United States, and within that responsibility to further the practice of democratic ideals. . . . The Board is, for example, not alarmed by indications from an applicant’s record that he has been identified with controversial activities in Europe. Such a person may well, if admitted to the United States, join the ranks of our ‘agitators,’ but is not our country strong enough to stand more agitators, even if their views do not coincide with our own, and is it not well to remember that the agitator, as in the days of our own thirteen Colonies, is sometimes in the right?”

For thirty-two years Centurions enjoyed his presence and friendship. He combined generosity and discrimination in dealing with institutions and men. In his modesty he was unaware of his greatness: he was much too kind to think much of himself. In administering a great foundation for the betterment of mankind, he never lost a sense of the power of spiritual values, seeing them as essential in the progress of the arts and sciences as well as in the performance of a civic duty. But he did not think of these things in a top-lofty way: rather he would think of himself as playing a hunch or putting up a grubstake for a person or cause. In his final report as President of the Carnegie Corporation he wrote some “warnings” to other foundation officers: “Don’t believe that you are able to outguess the future. . . . It does not pay to be too ingenious. . . . Every baseball player knows that it is not the total number of hits, but the way they are bunched that brings in runs and wins games. It is so in foundation affairs. . . . No more important lesson can be learned than that the key to success lies not with money but with friends, with the people with whom one works.”

Geoffrey Parsons

1943 Century Memorials

Related Members

Member Directory Home-

Hugh BirckheadClergymanCenturion, 1908–1918

Hugh BirckheadClergymanCenturion, 1908–1918 -

Charles ButlerArchitectCenturion, 1914–1953

Charles ButlerArchitectCenturion, 1914–1953 -

Clyde FurstSecretary, Carnegie FoundationCenturion, 1920–1931

Clyde FurstSecretary, Carnegie FoundationCenturion, 1920–1931 -

Frank J. GoodnowProfessor, Columbia CollegeCenturion, 1894–1939

Frank J. GoodnowProfessor, Columbia CollegeCenturion, 1894–1939 -

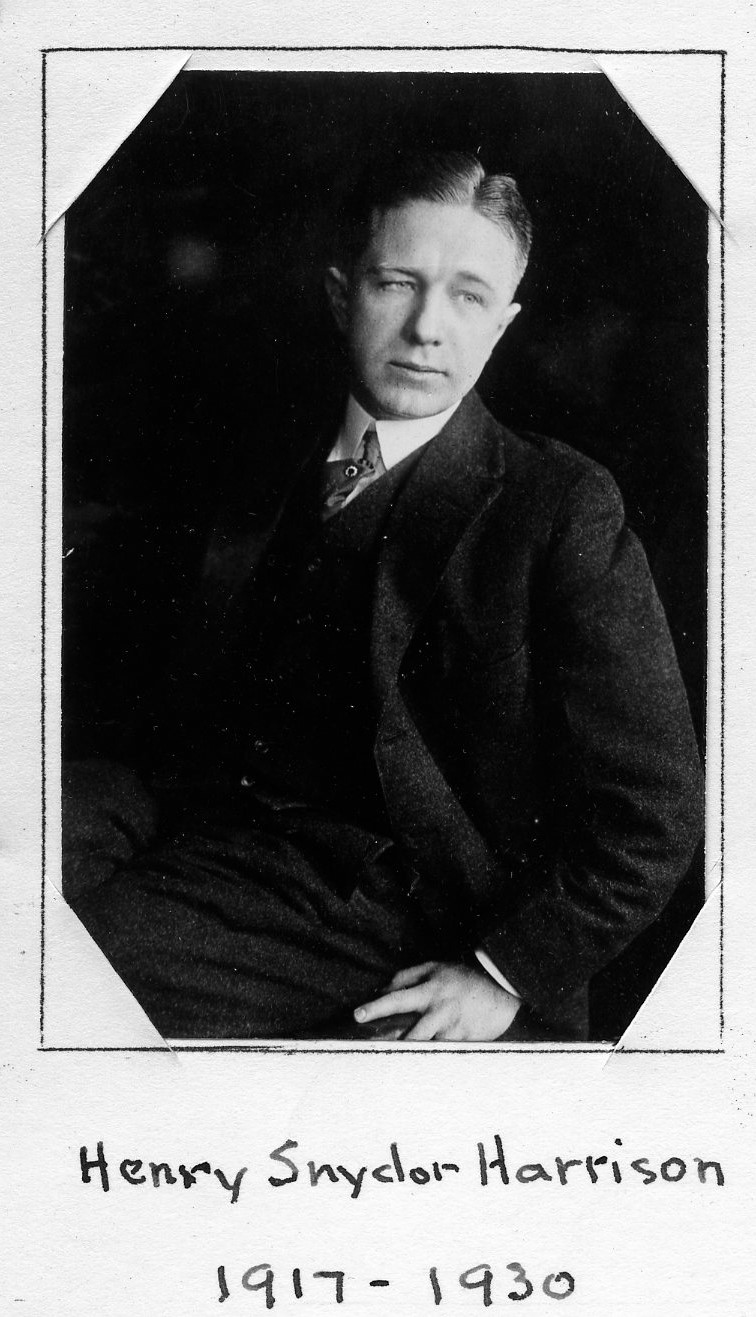

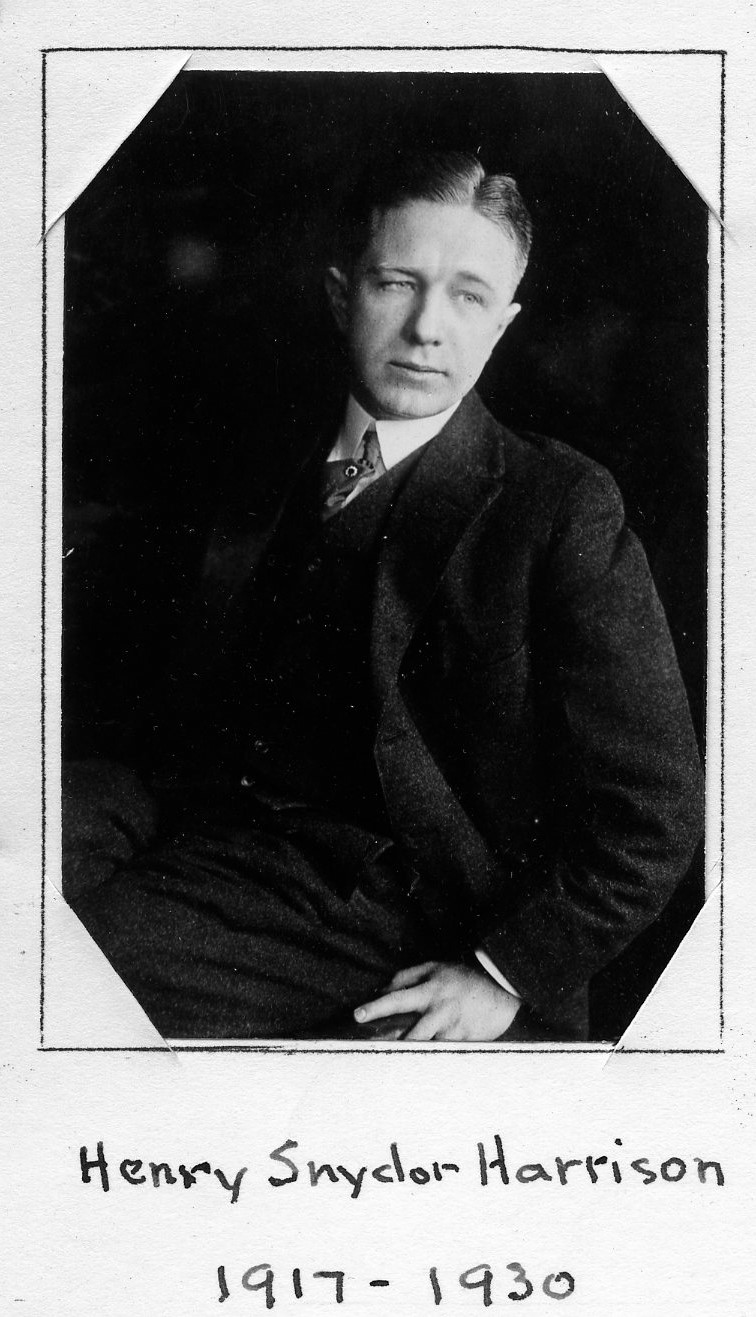

Henry Sydnor HarrisonNovelistCenturion, 1917–1930

Henry Sydnor HarrisonNovelistCenturion, 1917–1930 -

Herbert Edwin HawkesDean of Columbia CollegeCenturion, 1921–1943

Herbert Edwin HawkesDean of Columbia CollegeCenturion, 1921–1943 -

David KeppelPrint DealerCenturion, 1918–1934

David KeppelPrint DealerCenturion, 1918–1934 -

Russell C. LeffingwellAssistant Secretary of the TreasuryCenturion, 1919–1960

Russell C. LeffingwellAssistant Secretary of the TreasuryCenturion, 1919–1960