Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

Paul L. Ford

Author

Centurion, 1892–1902

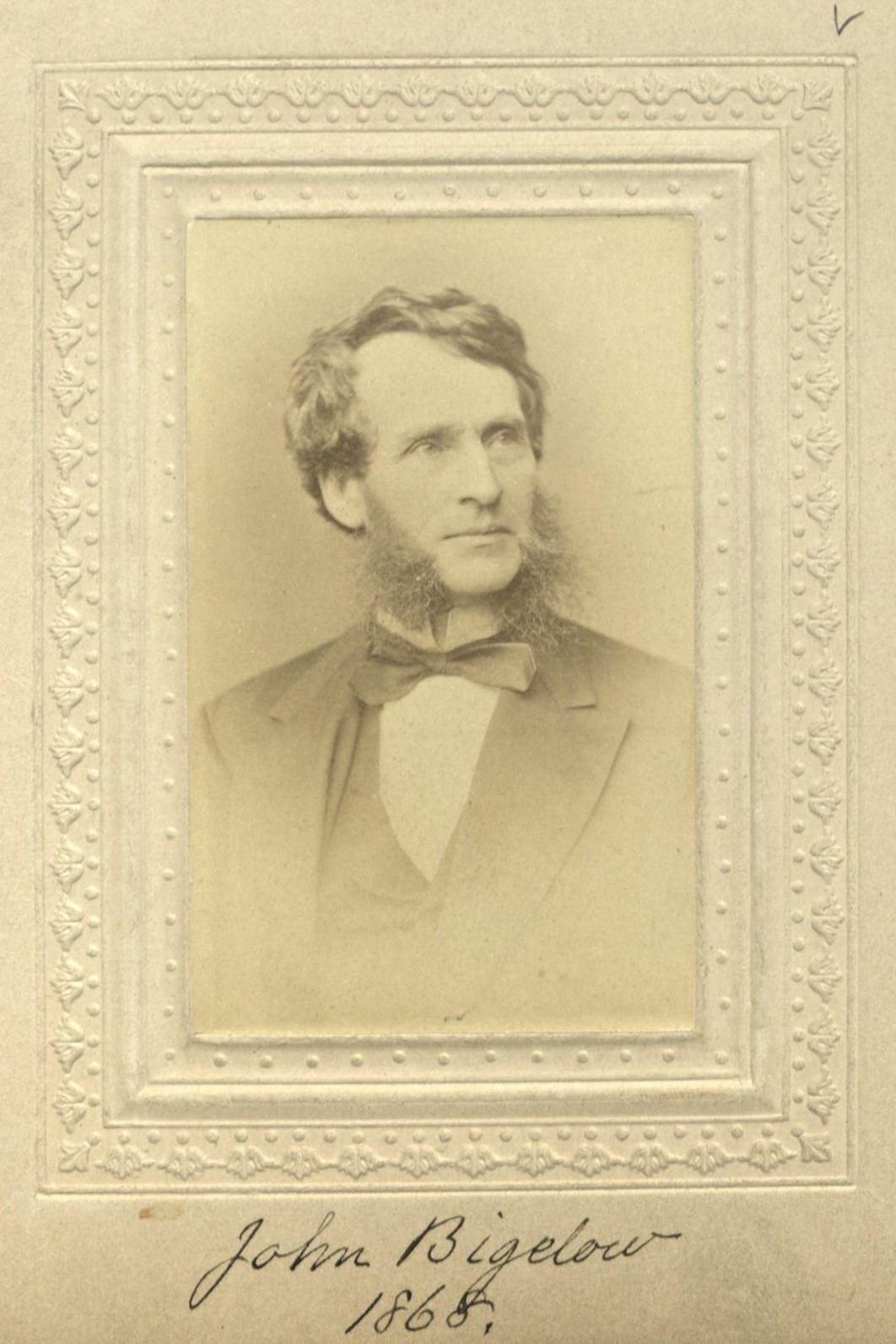

John Bigelow and Daniel Huntington

New York (Brooklyn), New York

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age twenty-six

Sleepy Hollow, New York

Archivist’s Notes

Brother of Worthington C. Ford; great-grandson of (nonmember) Noah Webster

Century Memorial

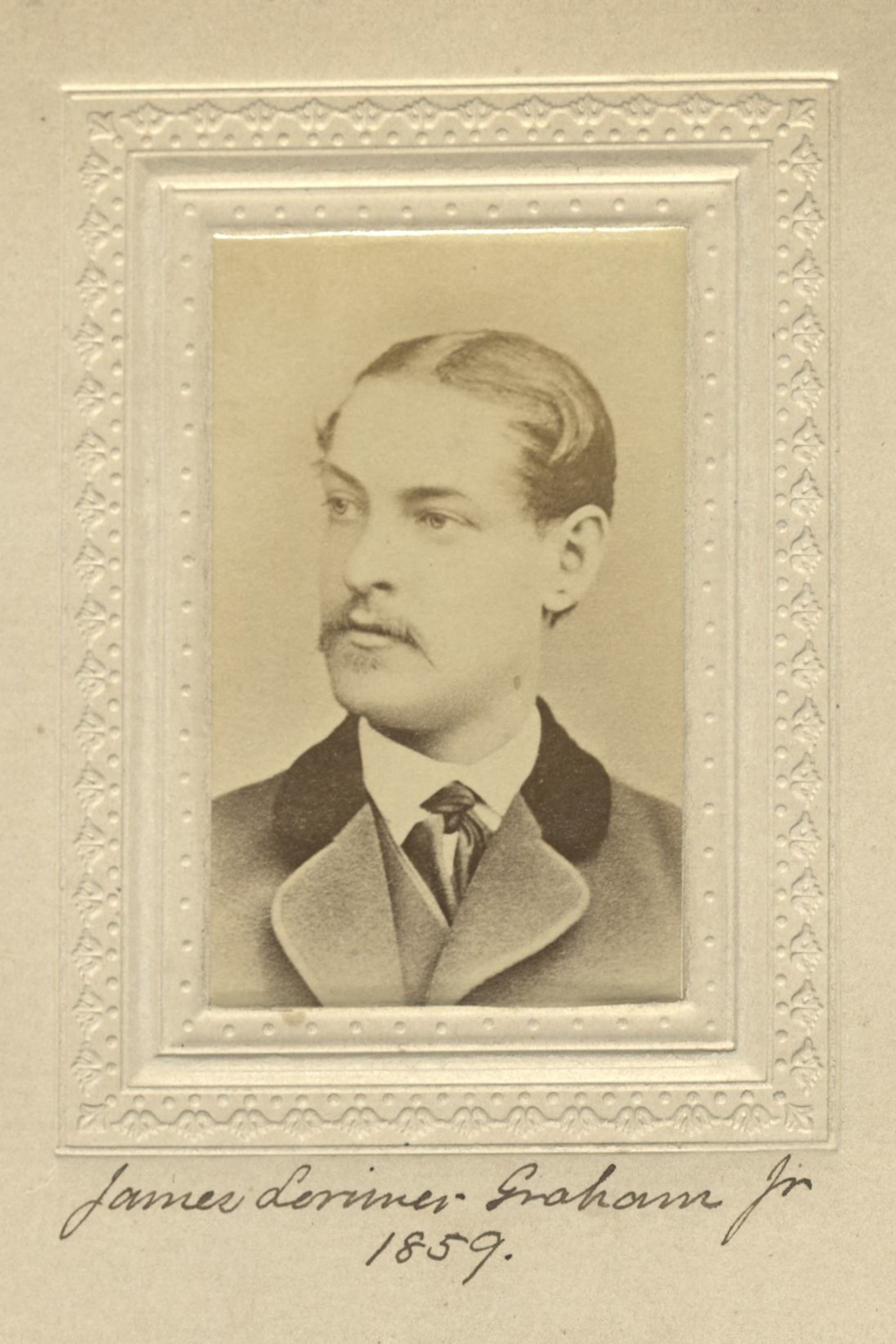

The career of Paul Leicester Ford, cut off in its early prime, held much of solid and brilliant achievement as well as of varied promise. Of pure New England stock, he included in his ancestry the lexicographer, Noah Webster, and President Chauncey of Harvard. An accident in childhood made him an invalid for some years, and most of his education was had in the remarkable library of his father, largely historical; while still a boy he engaged in bibliographic work of serious value, which he continued and expanded later. He was still very young when he issued the standard edition of the works of Jefferson and the monographs on Washington and Franklin, which showed the alertness and independence of judgment he brought to research in fields already well tilled. His memory was accurate, minute, and tenacious, and his power of assimilation of material extraordinary. His active imagination, his keen observation, his intense interest in men and affairs, and his fondness for bold and original generalization might, with the discipline of study and experience, have made him an historian of a relatively novel and really high type had he not turned his energies to the production of fiction. In this direction his success, whether measured by popularity or by the individuality of his work, was noteworthy. Of literary form he was impatient, and though there are passages in his novels of much force and simplicity, the swift-running current of his composition swept into his pages many bits of triviality and carelessness that a sober revision would have excluded, while he was over-lavish with detail and incident and crowded his books with minor characters. But these tendencies did not prevent the reader from being held firmly in the grip of his story and in the development of his personages. So far as his method can be classified, he was a realist, and his characters have always a definite relation to life as he saw it among his fellows. His first book, The Honorable Peter Stirling, is the best exposition that we have of the actual working of American politics among the teeming population of a great city; and his Janice Meredith, among the first of the recent flood of “historical” novels, is singularly informing as to the actual life and motives of the Revolutionary period, which ordinarily we regard through the refracting mist of tradition. We could get more truth from Mr. Ford’s historical romance than from the romantic history on which our youth had so long been nurtured. From his books, as from personal intercourse with him, one got the impression of restless, abounding energy. The range of his interests, as of his labors, was very wide and varied, and the play of his mind, though sometimes erratic, was often illuminating. Weighing what he was and did with due regard to the adverse conditions with which he had to contend, the years of suffering and weakness of his childhood and youth, the opportunities which did not tempt him for a life, at most, of elegant dilettantism, our sense of loss is deepened that the bright, virile mind, with so rich an accomplishment, should so soon have been quenched. The Century is especially indebted to him for his expert service in arranging and cataloguing the Graham Library.

Edward Cary

1903 Century Association Yearbook