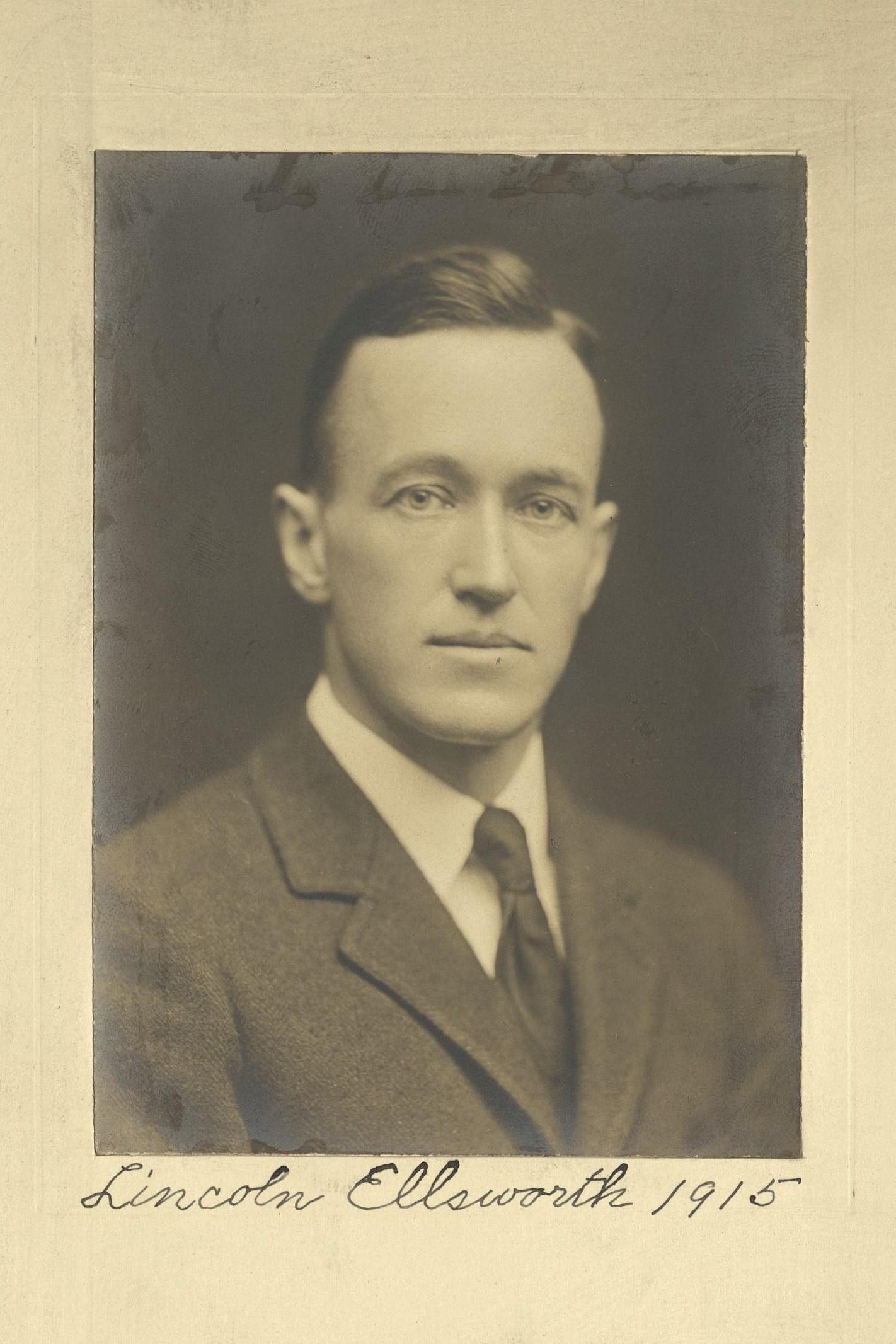

Civil Engineer/Explorer

Centurion, 1915–1951

Born 12 May 1880 in Chicago, Illinois

Died 26 May 1951 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Markillie Cemetery , Hudson, Ohio

, Hudson, Ohio

Proposed by James W. Ellsworth and Amos F. Eno

Elected 6 March 1915 at age thirty-four

Archivist’s Note: Son of James W. Ellsworth

Century Memorials

Ellsworth’s father [James W. Ellsworth] planned that Lincoln should go into the family coal business, and accordingly sent him to Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School and the Columbia School of Mines. But Ellsworth harbored powerful urges to go to unknown lands where no man had gone before and to solve the enigmas of geographic science which lie on the frontiers of knowledge. This innate drive took him to the wilds of Canada, to the crags of the Andes, to the South Polar regions, and to the Northern Arctic. He always managed eventually to get back safe and sound—though his father died thinking him lost in the Arctic.

He was one of the great explorers of the time. After World War I he went on several minor explorations, but his first big one was for Johns Hopkins University in 1924. The purpose was to make a geological survey across the Andes from the Pacific to the headwaters of the Amazon through Peru.

Back in New York, he and Roald Amundsen planned a flight to the North Pole. Ellsworth got his father to sponsor this enterprise, and on May 21, 1925, two planes took off from Spitzbergen and headed due north. They had a very bad time, ran into storms, were compelled to land short of the pole, and finally abandoned one of the planes. With great difficulty, they got the other plane into the air and made their way to a point in the open sea a mile off North Cape, where a sealing vessel found them.

Amundsen and Ellsworth tried again the next year, but Admiral Byrd had beaten them to the pole by three days.

In 1931 he attempted with Captain Sir Hubert Wilkins, the English explorer, to survey the underwater areas of the North Pole in a submarine, but they could not make the craft operate properly. He made several exploration trips by plane to the Antarctic, however, in the course of which he laid claim to 300,000 square miles of new land on behalf of the United States.

He was a gay and gallant person, always optimistic but never foolish. His preparations were always carefully made and the fact that he always succeeded in returning, where so many other explorers failed, is a testimonial to his competence and care. To associate with him was like opening the window to fresh air: he was not in the least interested in the housekeeping troubles of civilization, but he lived in a world where man seems closer to God.

George W. Martin

1951/1952 Century Association Yearbook

Ellsworth was born in Chicago, the son of a wealthy businessman. His mother died when he was eight and his father, James Ellsworth, was often away on business trips to New York and Europe. Ellsworth was not close to his father, but he had enormous admiration for him. He later remarked, “One of the things that made me persist in the Antarctic in the face of sickening discouragements was my determination to name a portion of the earth’s surface after my father.” It was his father who sponsored him for the Century in 1915.

Ellsworth’s initial exposure to polar adventures began on May 21, 1925, when he, Roald Amundsen and four other men set out in two Dornier flying boats on a mission to be the first to fly to the North Pole. The planes were forced down onto the ice and the explorers spent 30 days trapped on the surface. After chopping out a runway, one plane with all six men on board made its way back to Spitzbergen, their starting point. The plane landed with just 23 gallons of fuel left.

In 1926, Ellsworth and Amundsen announced their plans to pilot a dirigible across the North Pole to Alaska. Fourteen other men joined them as they began the historic crossing in early May. The journey across the polar sea from Europe to a point north of Nome took 72 hours and covered 3,393 miles. After four more expeditions to Antarctica in the 1930s, Ellsworth announced plans in early 1939 for yet another expedition, but it was cancelled because of World War II. His expeditions were the last privately financed ones.

According to William Daniel’s memoir, Ellsworth spent most mornings at the Club where he “regularly occupied the large chair in the southeast corner of the Reception Room on the first floor. He conversed with another member or read his mail or morning newspapers.”

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)