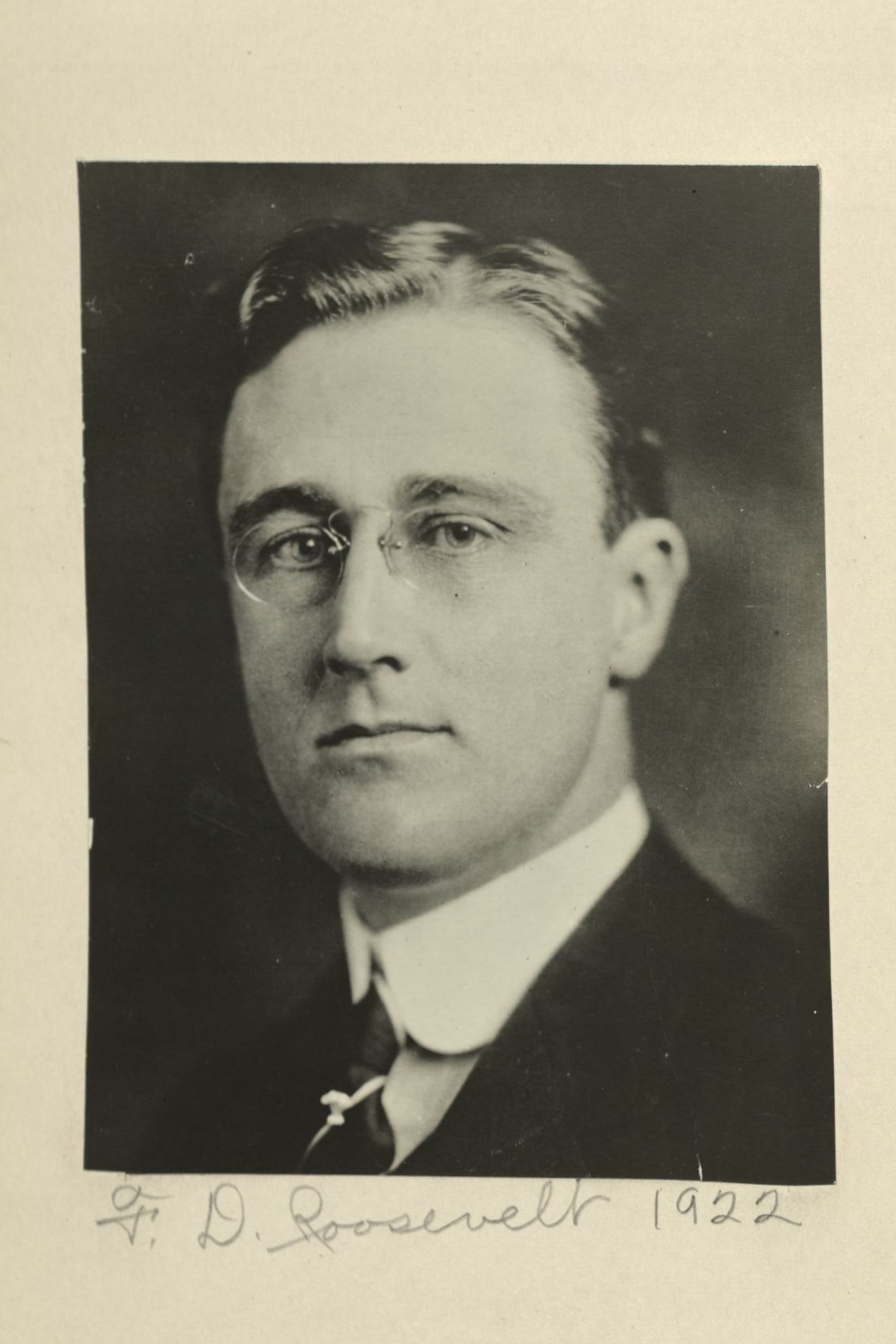

Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

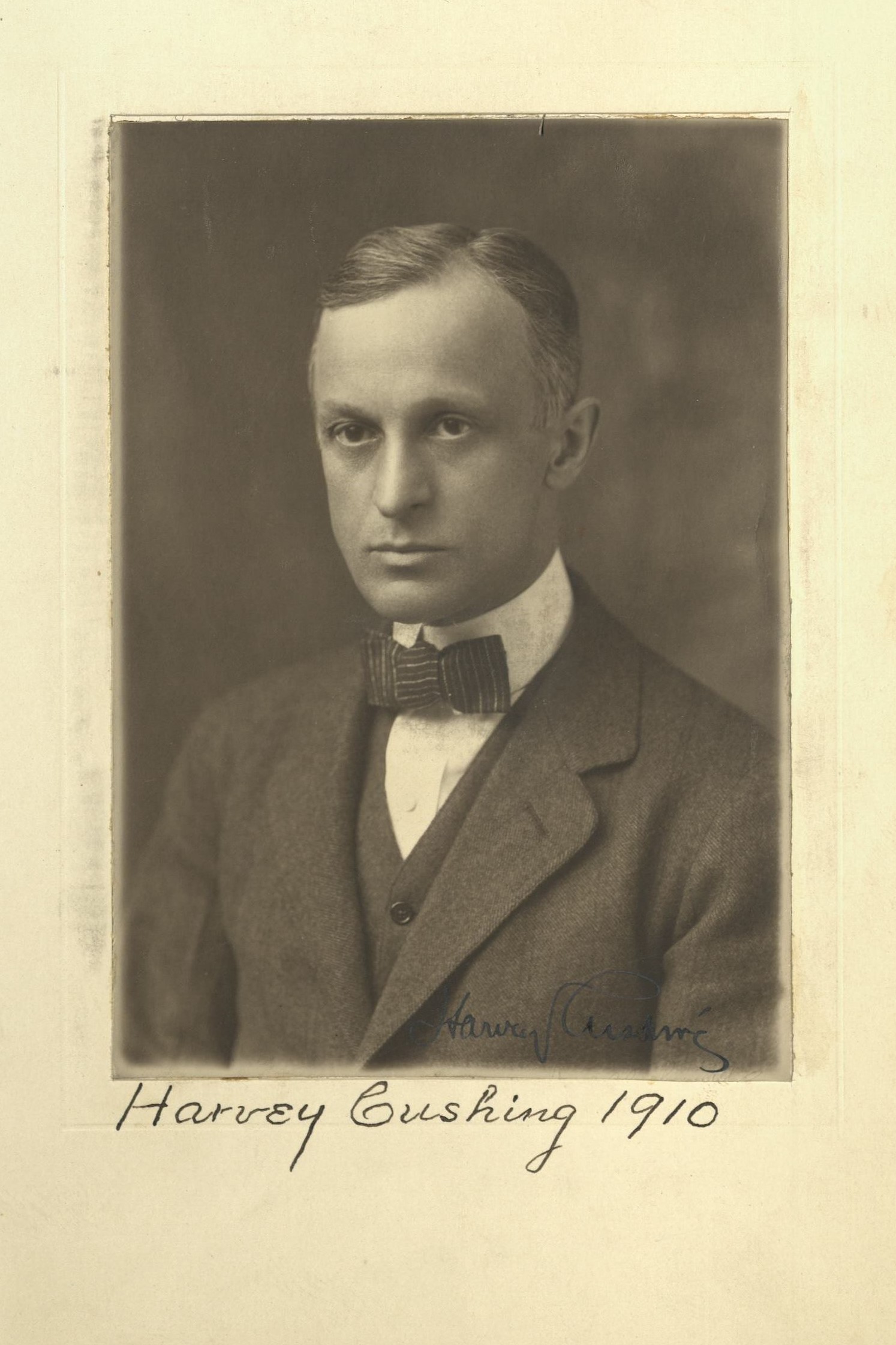

Harvey W. Cushing

Surgeon/Investigator

Centurion, 1910–1939

Simon Flexner and Grosvenor Atterbury

Cleveland, Ohio

New Haven, Connecticut

Age forty-one

Cleveland, Ohio

Archivist’s Notes

Father-in-law of William S. Paley and John Hay Whitney

Century Memorials

The general public knew Harvey Cushing as a great brain surgeon, the most famous in America. The judgment of his peers sustained this view and granted him much more. For he was a great physician in the broadest sense of the word. The technique of his delicate operations became standard around the world as they developed and were described in article after article. But already in 1912, while still at Johns Hopkins, he had published a monograph on the pituitary gland which still stands as the classic study of this most important of the ductless glands. The ingenious and infinitely deft technique of his surgery was, from this point of view, only the servant of a great scholar. It was at the Harvard Medical School and in Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston that he passed the most important years of his career, from 1912 to 1931. After two years of retirement, he made his late and happy connection with Yale (where he had gone as an undergraduate) as professor of neurology and adviser in the field of medical history, and, incidentally, president of the Elizabethan Club. His public services were as numerous as his many honors. From 1917 to 1919 he served as director of United States Field Hospital No. 5 in France and was made senior consultant in neurology for the A.E.F. Often beginning to operate at 8 a.m. and working through to 2.30 o’clock the next morning, he yet found time to write a million-word diary of the war, published under the title, “From a Surgeon’s Journal, 1915–1918.” But then in the thick of his labors at Harvard he had found time to write “The Life of Sir William Osler,” which won a Pulitzer prize. On the personal side of his life, a Centurion writes out of an old friendship words too revealing to be spared:

“I can think of no more ideal member of the Century than Harvey Cushing, except for the fact that he so rarely came to the Club. During his intensely active years before his retirement from the Brigham Hospital where his work was largely life and death operations on patients sent to him as a last resort, he could not often get away. And after his retirement he rarely left New Haven because he was partially crippled.

“It was always especially hard for me to realize that his legs had ‘gone bad,’ because our life-long friendship began in the old ‘gym’ at Yale, just fifty years ago, as two very green freshmen, who were fond of tumbling on the mats, turning somersaults from the spring-boards and doing tricks with the rings and bars. Cushing was a trained, all around athlete and had an ‘errorless’ record on the Varsity baseball team.

“But he was a good scholar as well—an excellent example of mens sana in corpore sano. He would have succeeded in any profession. Up to his senior year he seriously talked of joining me in architecture. He had the aesthetic appreciation and an unusual facility in drawing and his diaries, which he kept conscientiously from college days all through his life, were illustrated in pen and pencil. Even the anatomical illustrations in the early publications of his surgical researches were his own work and of high quality. But he was born with ‘surgery’ in his veins—a family inheritance and we probably lost a great architect when he finally decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, elder brother and others in his family.

“His Baltimore days when he lived next to Dr. Osler on most intimate terms, saw the beginning of his literary interests—chiefly in the field of ‘greater medicine’—which led to the unusually fine collection of rare medical books which he has left to Yale to form the nucleus of one of the greatest historical medical collections in America, to be called the Cushing Memorial Library and to be housed in a new wing of the Sterling Hall of Medicine at Yale.

“But Osler’s influence carried far beyond the literature of medicine. He was, I think, the greatest influence in Cushing’s life, his inspiration and model as well as his teacher in the science and art of medicine. In the long years of their intimacy Harvey Cushing acquired qualities that even the great medical leaders like Welch, Halsted, and Finney, with whom he associated at Johns Hopkins, could not inspire in him. Anyone who knew Osler’s charm would recognize its counterpart in Cushing if they knew him socially as a friend. No one but Osler could be as charming as Cushing.

“He would have been a great surgeon without Osler’s influence. He had the enthusiasm, the extraordinary faculties, the absolute, concentrated devotion to his profession—to the exclusion of all else where it might interfere with his service to medicine—the technical equipment and the manual and mental dexterity and the indomitable will to secure his success and greatness as a surgeon and a master of research. But if you have read his ‘Life of Osler,’ (in which, by the way, you will find not a single mention of Cushing), you will discover the key to certain qualities that developed into a rare fascination, known best to his intimate friends, but making him socially an utterly charming companion.”

Geoffrey Parsons

1939 Century Memorials

Cushing was a neurosurgeon and a pioneer of brain surgery. He was widely regarded as the greatest neurosurgeon of the 20th century and often called the “father of modern neurosurgery.”

Cushing was born in Cleveland, the youngest of ten children, and he was the fourth generation of his family to enter medicine. Cushing graduated from Yale in 1891, and received his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1895. In 1896, he studied surgery under the guidance of a famous surgeon, William Stewart Halsted, at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, in Baltimore.

Cushing married Katharine Stone Crowell in 1902. They had five children: two boys, William Harvey and Henry Kirke, and the three famous Cushing sisters: Mary Benedict Cushing, who married Vincent Astor and painter James Whitney Fosburgh; Betsey Cushing, wife successively of James Roosevelt, FDR’s oldest son, and John Hay Whitney; and Barbara Cushing, socialite wife of Stanley Grafton Mortimer and William S. Paley.

In 1912, he published a landmark monograph on the pituitary gland, and that same year he became surgeon in chief at the new Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston. He served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps as a surgeon with the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I. Years later (1938) he published a classic study of war wounds.

Cushing received the Pulitzer Prize in 1926 for a biography of one of the fathers of modern medicine—Sir William Osler. In 1930, He was awarded the lister Medal for his contributions to surgical science, and that year he delivered the lister Memorial lecture at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Cushing was also a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, retiring in 1932. From 1933, until his death, he was the Sterling professor of neurology at Yale University School of Medicine.

James Charlton

“Centurions on Stamps,” Part I (Exhibition, 2010)