Clergyman

Centurion, 1914–1938

Born 24 August 1859 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 4 December 1938 in Whippany, New Jersey

Buried Holy Rood Cemetery , Morristown, New Jersey

, Morristown, New Jersey

Proposed by Frederic R. Coudert and Paul Fuller

Elected 4 April 1914 at age fifty-four

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

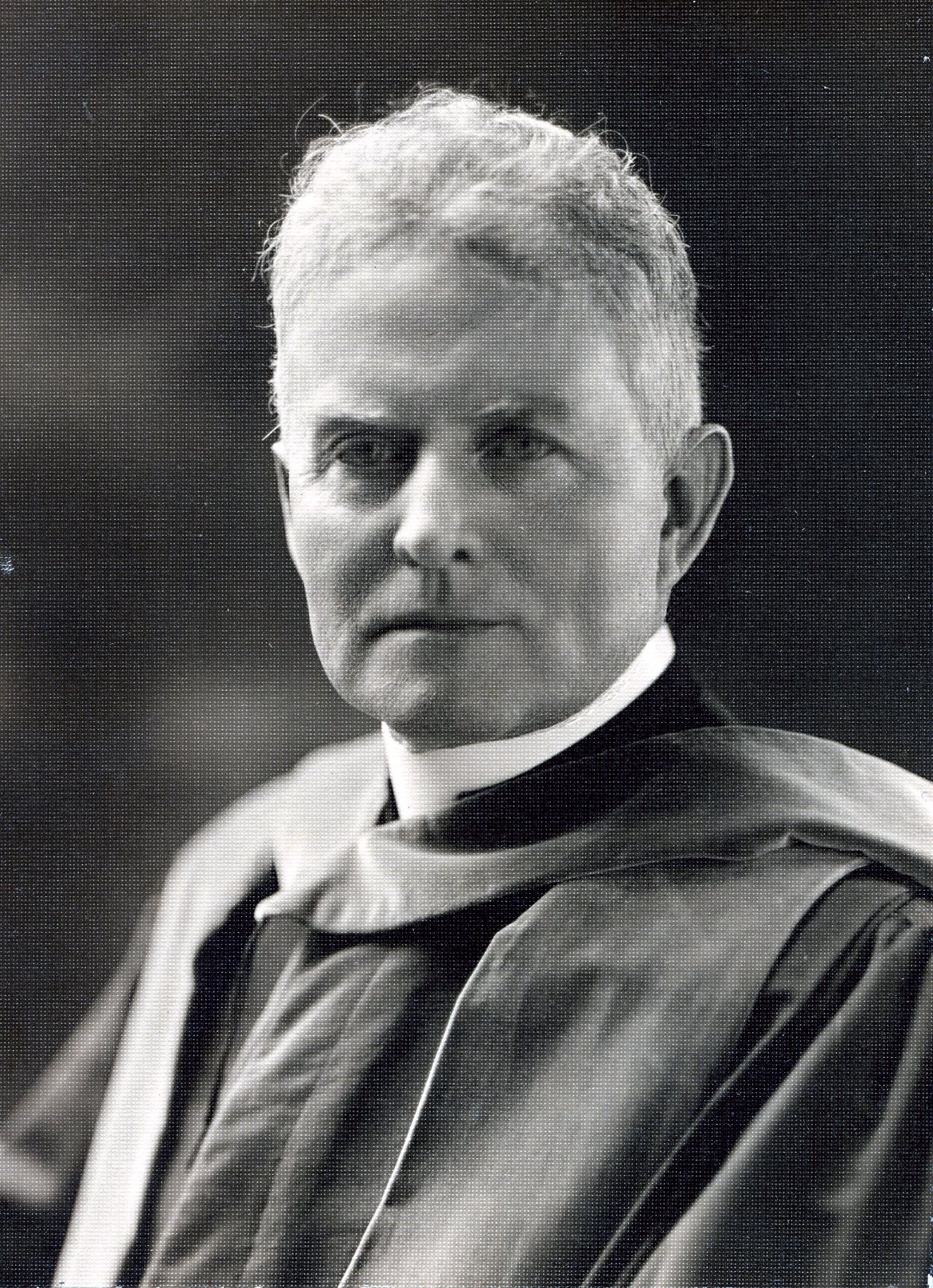

The home of the Century became a more luminous place when the Rev. Cornelius Cyprian Clifford entered it. He was a learned man, in his chosen fields probably as learned as anyone in this country or abroad. Columbia University included him in its faculty of philosophy with good reason. But he wore his learning comfortably, easily. If his conversation was always that of a scholar, his knowledge never clouded either his humor or his exposition. His wisdom pervaded his talk without obtruding itself upon the listener.

There can be few Centurions who were unfamiliar with his slight figure, merry blue eyes, and cleanly carved face or unready to smile a welcome when they saw him. Rarely did a week go by without his turning up at the long table for lunch or dinner. Thursday evening often found him dining with Dr. Carrel and Mr. Coudert. But he belonged to the whole Club. There can have been few Centurions as charming and stimulating in their companionship as he, as good at listening as he was learned and witty in his talk. It was, indeed, in general conversation, in a group, that he most shone. These personal words by a Centurion, a friend for over thirty years, may help to explain the unique flavor of Father Clifford’s culture:

“He was in the fullest sense of the word a ‘civilized’ man, heir to the best thoughts of the men who made Western civilization. I think the years he spent with the Jesuits as a novice at Woodstock, Md., as a teacher in New York, and as a teacher and a priest in England, gave him a special scholarship and culture that he could not have developed, perhaps, in other surroundings. He was a good Latinist as one might expect after such a training and a keen metaphysician (of the Aristotelian-Thomist school) who was well abreast of ‘modern’ thought. In a word, he was a fine example of that thing which is growing more and more rare nowadays, a scholar who would have been at home with Petrarch, Erasmus, and, most of all, perhaps, Sir Thomas More.”

The same Centurion recalls the fact that a portrait of Father Clifford by another Centurion, Augustus Vincent Tack, hangs in the Jesuit House at Oxford—Campion Hall —and that every year Father Clifford Day is celebrated there by a banquet.

The whole record of his life shows an extraordinary mingling of brilliancy and simplicity. In his career as a priest there was little that he had not done, there were few countries he had not visited, few intellectual heights the air of which he had not breathed. Yet he elected to devote the better part of his life to a country parish at Whippany, New Jersey. Such a rectorship could not be hid. The Church of Our Lady of Mercy, seating two hundred persons, became as a shrine, to which flocked visitors from all over the country. He was a rector first and his articulate, forthright exposition of Roman Catholic doctrine from the pulpit drew many to the Church. Beside that stood his profound knowledge of liturgy and his discriminating taste which slowly, across the years, through gifts from loyal friends of works of art representing the great Gothic centuries, transformed his parish church into a noble medieval sanctuary. It would be difficult to exaggerate what he meant to his parishioners. They loved him. He was an essential part of their lives. And they came first in his thoughts. The vestments he wore were made by the women of the parish under his expert direction. By reason of a clear mind and his articulate, candid speech he was in great demand in the city for lectures in the homes of laymen. He spoke freely of every contemporary topic of discussion. His interviews with the press were models of frankness. When evolution and the Bible were on trial at Dayton, Tennessee, he remarked: “We have just emerged from a period of storm and stress brought about by the newspapers, which in their factitious way can often accomplish what great leaders of thought are unable to do. Merely by reporting in their inimitable newspaperish manner the utterances of an immature young school teacher they did what philosophers have failed to do. . . . Bryan was a good man but not a wise one. He did more harm to religion among thousands of so-called Fundamentalists than can be calculated, since he preached only the terrible alternative of a literal interpretation of Genesis and black infidelity.”

He wrote incessantly. His books include “Introibo,” “The Burden of Time,” and “Obediences of Catholicism.” He contributed verse to English periodicals. He had lectured in many seminaries and universities. In the bulletin of the Philosophy Department of Columbia for 1938–1939 he was scheduled to give Philosophy 175–176 on Scholasticism, twice a week throughout the year. Its subject matter was thus defined: “Physics, metaphysics, and the supernatural; on the confines of mysticism; Henri Bergson and Miss Underhill.” If he was seldom as scholastic as that at the Century, he was much more; and he will be unforgettably missed.

Geoffrey Parsons

1938 Century Memorials