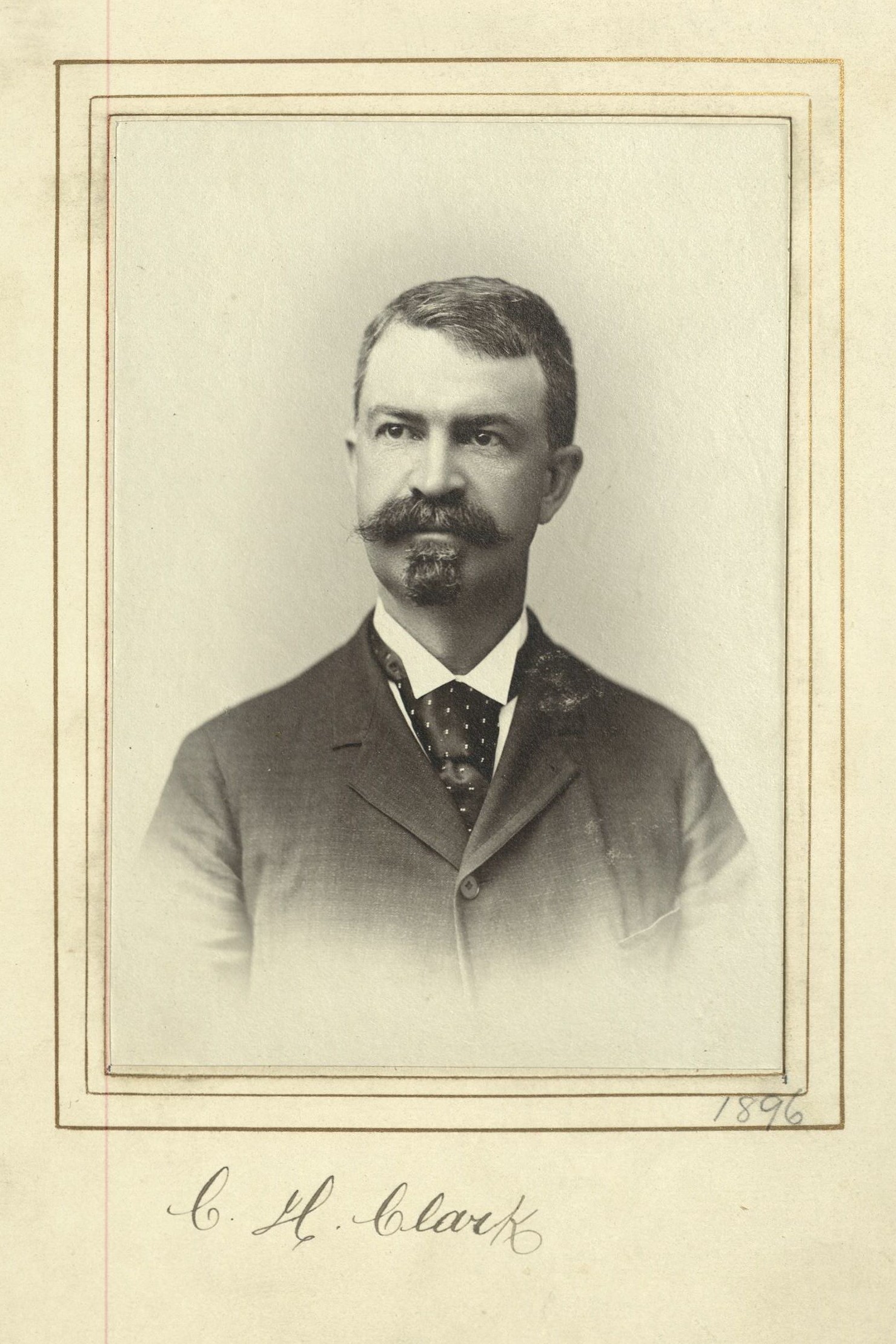

Professor of Political Economy

Centurion, 1896–1938

Born 26 January 1847 in Providence, Rhode Island

Died 21 March 1938 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Lakewood Cemetery , Minneapolis, Minnesota

, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Proposed by William Crary Brownell and Richmond Mayo-Smith

Elected 7 November 1896 at age forty-nine

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

It is related of John Bates Clark that when the World War came to this country and college professors were asked to fill out a blank in which to note their special qualifications, he set down that he was qualified as “a chauffeur.” It was a time for action rather than for academic discussion, in his clearheaded view. More, the episode recorded a modesty and self-effacing shyness which were integral in his nature. He was, by general consent of his fellows, the greatest economic theorist ever produced in this country. Yet no one could be less dogmatic in his professional hours or more gently at ease among his friends at the Century. He was beginning his ninety-second year when he died and was thus the second oldest on this list. His companions in the club-house included such figures as Dean Van Amringe and Henry Holt, making in their prime a notable group of debaters upon the fate of the world.

As an economist he stood in the great succession, founded by Adam Smith, carried forward by John Stuart Mill and David Ricardo. His classic work, “The Distribution of Wealth,” published in 1899, applied the principle of marginality to all the factors of production and submitted the thesis that each of the factors of production—land, labor, and capital—tends to receive the share of the social product that it has respectively contributed to produce. The wages of labor, for example, tend to be determined by the productivity of labor. Other economists in other countries, notably Alfred Marshall in England, aided in the “heroic theoretical treatment” which resulted in the development of the modern marginal theory of value.

The statisticians have had their day since and the earlier theorists like Clark have been ridiculed for their assumptions of a state of perfect competition and conditions of “static equilibrium.” Of all the classicists no one was more aware than Clark of the distinction between “static” and “dynamic” economics or more explicitly stated it. Because of the bewildering complexity of economic forces, he held it necessary first to analyze and formulate the facts of an imaginary “static equilibrium” before advancing to the second stage of studying one by one the “dynamic” changes that are constantly upsetting the hypothetical equilibrium. The current methods of economics follow exactly this twofold approach, which Clark had already conceived if he did not ever practice.

He was always keenly alive to the practical problems of the day. In the days of the first Roosevelt he was an ardent upholder of the system of free enterprise and contributed his weight to the “trust-busting” attacks upon monopoly. In the year 1911 he became head of the Division of Economics and History of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and in the post-war period he warmly supported the League of Nations. For a hobby he made himself an expert cabinetmaker. His friends remember a library chair in his apartment that was a beautiful example of his skill both in designing and woodworking. It may not be fanciful to descry in this labor of construction as an amateur something of the essential quality of his being. As Dr. [Nicholas Murray] Butler said of him, at a banquet given in his honor on his eightieth birthday,

“He has seen deep down into the root of principle, he has developed principle, he has applied and interpreted principle. He has made his place and his fame permanent not by any patient and industrious accumulation and reclassification of facts, but by an insight which puts facts in their framework and their proportion.”

Geoffrey Parsons

1938 Century Memorials