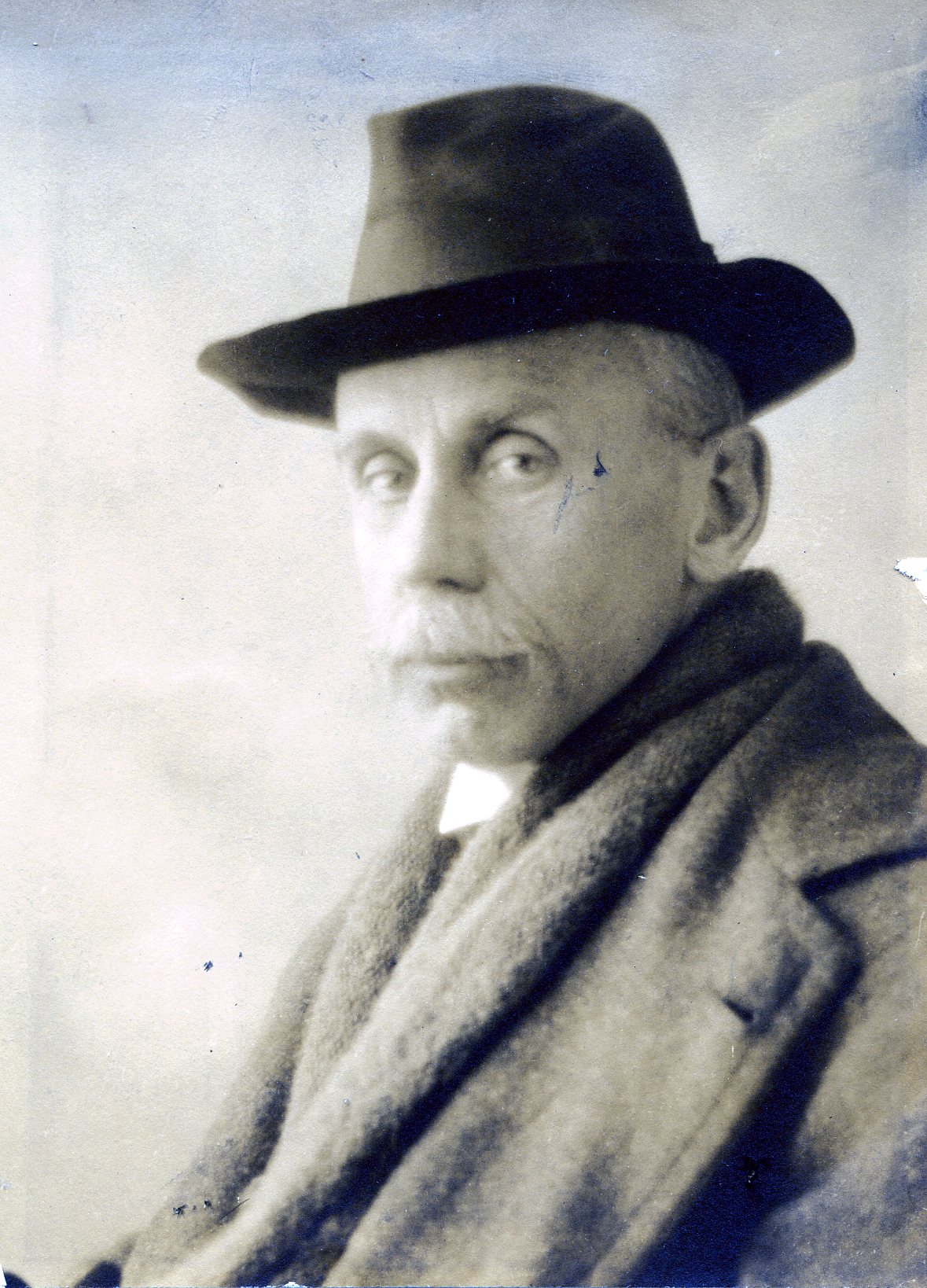

Artist/Architect

Centurion, 1905–1939

Born 29 June 1866 in New York (Brooklyn), New York

Died 26 January 1939 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Saint Matthew’s Episcopal Churchyard , Bedford, New York

, Bedford, New York

Proposed by D. Maitland Armstrong and F. Augustus Schermerhorn

Elected 4 March 1905 at age thirty-eight

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

There was a rare unity, a sweet perfection, in the nature of Allen Tucker. Yet there were sharp contrasts and apparent contradictions, too. He was gentleness itself, as members knew and loved him at the Century—kindly, affectionate, forbearing. Yet he could write to a fellow Centurion—he was an incessant daily letter-writer in an age of speed which has all but discarded the art—upon his hit-or-miss typewriter: “I have few virtues but thank Heaven I have never been tolerant.” To support his assertion various tales could be told of passionate battles with protagonists of what were to Tucker powers of darkness. A large and gracious luncheon was once interrupted by threat of physical violence, when an irritating and wrong-headed artist-writer of note attempted to overwhelm Tucker with his agile tongue. When fundamentals were in issue—wrong, compromise or cheating, in art or in life—the gentle Tucker became a furious St. George and the sharp sword of his mind dealt devastating blows. His detestation of German aggression in the last World War was so strong that when German hecklers attempted to break up an Allied meeting in Carnegie Hall, he rushed to the galleries to throw them out. As he was too old to enter the army, he joined the American Ambulance Service. His love of France was as basic as his distaste for England and the English. As he felt, so he spoke and acted.

Tucker was that rare creature, a philosopher in the field of his own art. His slender volume of lectures, delivered at the Art Students’ League and published in 1930 under the title “Design and the Idea,” ranks among the few really valuable endeavors by an artist to account for his own labor. His description of the creative artist has become famous: “To be one’s self, to be honest with one’s self, to do as one thinks, to follow one’s own vision and to develop that talent, that vision, all one’s life, is the way to learn to paint.” He made his own the Stevenson thesis that art is “a life to be lived” and in his praise of the creative artist as the only possible solution of the modern mechanized world, he wrote words which have an eloquent meaning for anyone who would really live. In a lecture upon “Balance” he said: “Life is a pulsing turmoil filled with terror and bravery and glory and to sit down and paint pictures of bleating sheep and simpering females is not to show much appreciation of what is going on about us.” And finally, in a letter: “Life is the one thing men are afraid of. Death? It is life that scares them all to pieces.”

The singleness of this passionate, original nature begins to appear. Its source was an utter and intense sincerity. His talent for friendship matched his talent for painting, and he trusted both. These were fundamentals of his being. He could not be false to either. Just how many friends he helped, privately, affectionately, tirelessly, his closest associates in the Century cannot pretend to guess; but giving to those he loved and admired was part of that “fierce” affection which was at the core of his nature. By the same test, how could he be tolerant of those peoples and individuals who fought his deepest convictions!

He was marvelously communicative. His talk was shot with wit and fancy, with quick laughter and high spirits. A friend has written of his humor as possessing the “bewitching quality of a child’s hilarity,” and that children understood him instantly. There can be few members who possessed a circle of friends in the club as warm and devoted as was his; certainly no friend ever gave more delightful companionship or greater loyalty than did he. With them in the club he played at chess or cowboy pool, or with ideas in that informal unregimented atmosphere of friendship which is the heart of the Century. His book of lectures is in the library. So is a slender volume of poems, “There and Here,” in which he set down those thoughts and feelings—especially about his war experiences—which his sense of color could not express. Many of them are on fire with laughter, with love, with anger. His interest in the theatre and in music was no less active and passionate. It was not in him to be “afraid of life” or any part of it.

Geoffrey Parsons

1939 Century Memorials