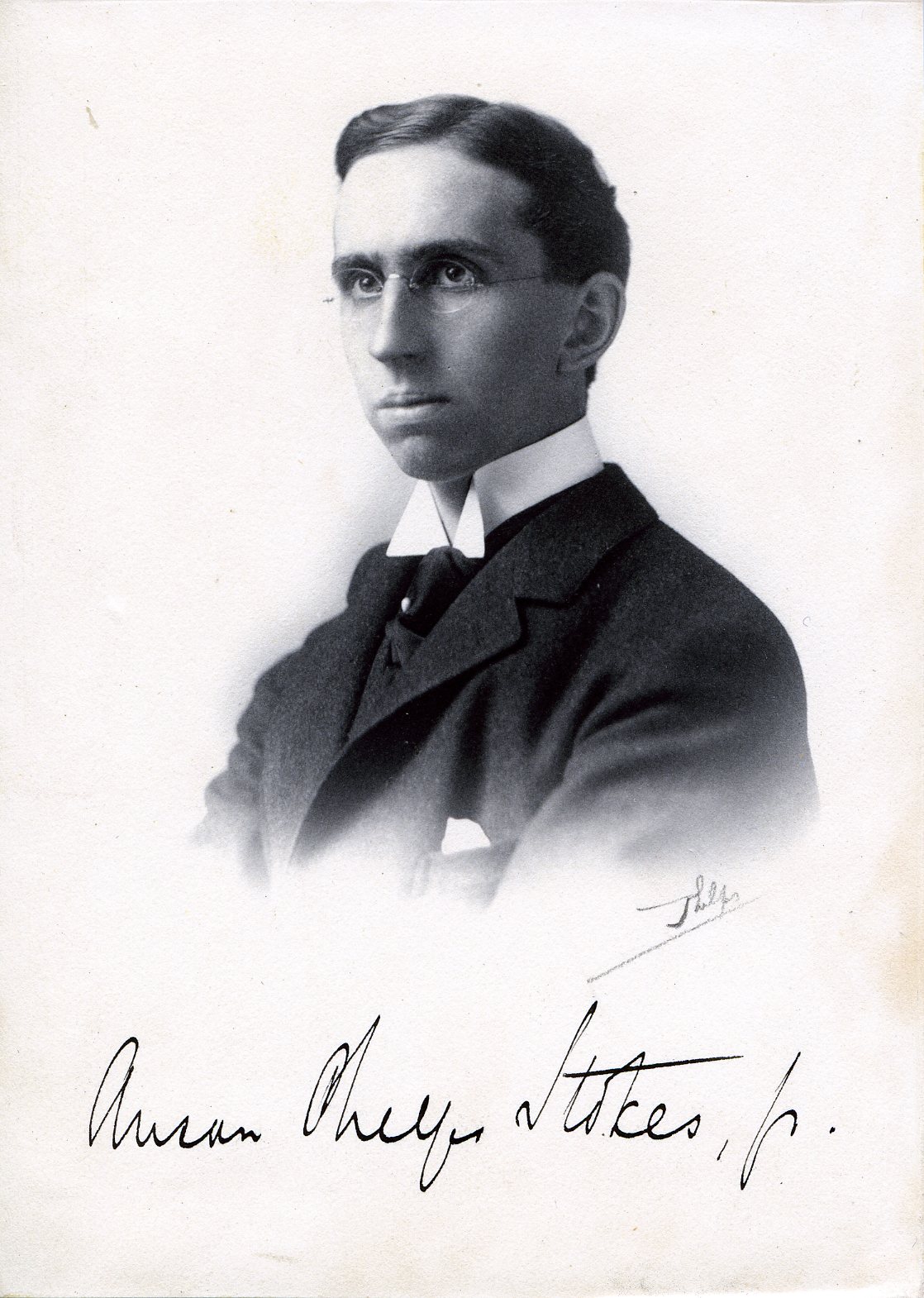

Clergyman

Centurion, 1908–1958

Born 13 April 1874 in New York (Staten Island), New York

Died 14 August 1958 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Buried Woodlawn Cemetery , Bronx, New York

, Bronx, New York

Proposed by David H. Greer and John C. Schwab

Elected 1 February 1908 at age thirty-three

Archivist’s Note: Son of Anson Phelps Stokes; brother of Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, Harold Phelps Stokes, and J. G. Phelps Stokes; father of Anson Phelps Stokes Jr. and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes

Century Memorial

How, even in so long a span of life, one man could have done so much in so many directions is mysterious to the friends of Anson Phelps Stokes. For he was a clergyman, the secretary of a great university, a fighter for social justice, a nature lover, an educator, a promoter of physical and mental hygiene, and a founder or trustee of literally dozens of welfare and philanthropic organizations. In among all these activities he found time to be a distinguished tennis player, one of the country’s first amateur golfers, and an expert trout and salmon fisherman. A devoted Centurion, he was proud that his father [Anson Phelps Stokes], his three brothers [Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, J. G. Phelps Stokes, and Harold Phelps Stokes], and his two sons [Anson Phelps Stokes, Jr., and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes] were all members.

He was born in Brighton, Staten Island, April 13, 1874. There was a tradition of great wealth through many generations on both sides of his family. His father, for whom he was named, was a banker, a political publicist, and a writer on economics.

From the time young Anson entered Yale, in 1892, the college and the university always held a top place in his attention. Three years after his graduation in 1896, he was appointed Yale’s Secretary, a position he held for twenty-two years, during which the college expanded into a university.

In these busy years, he supported the residential college plan, brought the alumni into closer relations with the university in a system which has since altered many other college communities, and he began the effort, continued through life, to build Yale’s endowment funds.

A story is told which gives a hint of the generous scale on which his family lived. Once, while he was an undergraduate, he telegraphed his mother, “Arriving Friday with some 96 men.” He meant a few members of his class of ’96. But Mrs. Stokes took it otherwise. “Can put up only 35,” she wired back.

At the time of his appointment at Yale he was studying to be a clergyman at the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, the town of Yale’s rival. Later, the job of Secretary—demanding enough, one would suppose—did not keep him from becoming assistant rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in New Haven, a post he held till 1918. When he resigned as Secretary in 1921, he became canon of the National Cathedral in Washington.

His interest in Negro progress was one of the preoccupations of his life. He was, for many years, president of the Phelps-Stokes Fund, devoted largely to Negro education. He was at one time a trustee of Tuskegee Institute. He argued the case for Marian Anderson before the Daughters of the American Revolution, which had opposed her singing in Constitution Hall. His brief for Miss Anderson was later published under the title Art and the Color Line.

A few titles of organizations he served as director or trustee suggest the scope of his enthusiasms. Among them are Wellesley College, the International Education Board, the Rockefeller Foundation, the American Academy in Rome, the Negro Encyclopedia, the Brookings Institution, and Yale-in-China.

His three-volume book, Church and State in the United States was published in 1950. It was, Alvin Johnson wrote in the American Historical Review, “without question the most extensive treatment of the historical development of the separation of church and state that has ever been published.”

When he was in New York, he often had lunch at the Century. He liked people. He made new friends at the Long Table and drew them into conversation about their special interests. Once he planned a private dinner for a group of persons interested in race relations. To avoid any misunderstanding, he consulted the House Committee in advance. No, they said, there could not be the slightest objection to his Negro guests. But if he intended to bring ladies into the Club, he must go elsewhere!

We whom he has left in the Century are proud that Anson Phelps Stokes was with us for half a century.

Roger Burlingame

1959 Century Association Yearbook